I’m very sad and sorry about the passing of William Goldman, whom I respected enormously as a screenwriter and book author, and whom I actually knew on a personal basis.

We were hardly “close” — we never talked about the difficulty of writing or women problems or anything personal. But I felt that I genuinely knew Bill as a human being, at least to some degree. I always felt settled and relaxed in his presence. And he seemed to have a certain regard for me also. At least to the extent that he took me to lunch four or five times, and always at the same elegant Upper East Side eatery that was near his apartment.

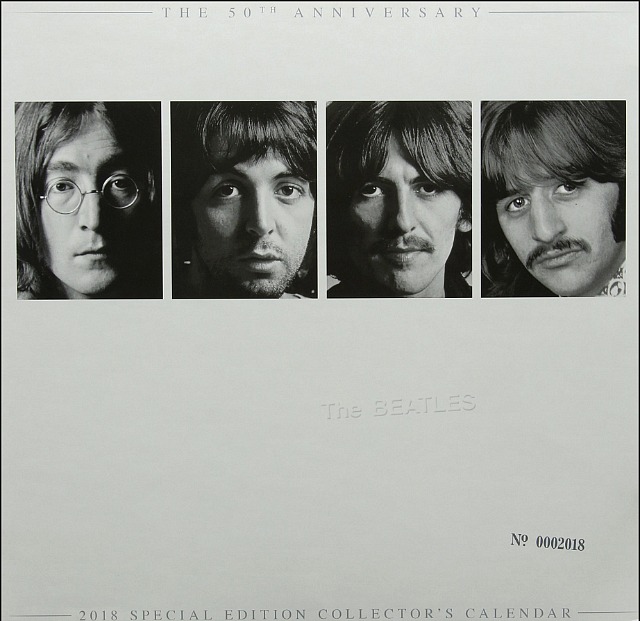

I felt profoundly honored that the writer of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Hot Rock (one of my all-time favorite ’70s films), Marathon Man and All The President’s Men read and admired my column. I once told myself “Jesus, I’ve gotta be doing something right if Goldman likes what I’m doing.”

We began our occasional correspondence (a phone call now and then, back-and-forth emails when something had happened) sometime in the early to mid ’90s, or when I was writing and reporting for Entertainment Weekly and the L.A. Times Syndicate. But we didn’t actually sit down and break bread until ’06 or ’07, or after Goldman became a regular Hollywood Elsewhere reader.

The only time our relationship hit a ditch was when I told Goldman that I didn’t much care for Hearts of Atlantis (’01), the Anthony Hopkins film based on a Stephen King novel. He didn’t speak to me for several months after that.

He always called me “Jeffrey” — never Jeff. He invited me up to his place once, and I remember there was a kind of shrine to Butch Cassidy as you walked through the main door. And who could blame him?

The last time I saw Goldman was at a press luncheon at 21, maybe six or seven years ago. He was sitting at a table with Joan Didion. The room was noisy and chattery and it was hard to say anything that mattered, but I belted out a hale and hearty “hey, Bill!” He looked at me with a slight smile and a slight nod. And that was it. We didn’t correspond again. And I’m sorry about that.

There’s a DVD documentary about Gunga Din, and Goldman’s commentary about that 1939 film is so eloquent when he explains why some people are so moved by that film, and particularly by the “stupid courage” shown at the very end by Sam Jaffe‘s titular character.

Famous quote: “I [don’t] like my writing. I wrote a movie called Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and I wrote a novel called The Princess Bride and those are the only two things I’ve ever written, not that I’m proud of, but that I can look at without humiliation.”