Steven Soderbergh has said time and again that the reaction to his two-part, 258-minute Che, a brilliant, thinking-man’s epic about Che Guevara, was a downish turning point. He’s told N.Y. Times interviewer Dave Itzkoff in an 8.10 article that “he was changed for the worse” by it.

Che was critically praised, but its commercial failure “soured” him on high-minded prestige films. “Che beat that out of me,” Soderbergh says.

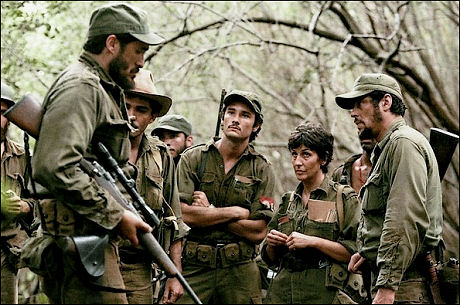

Posted from Cannes on 5.21.08: I know I predicted this based on a reading of Peter Buchman‘s script, but the first half of Steven Soderbergh‘s 268-minute Che Guevara epic is, for me, incandescent — a piece of full-on, you-are-there realism about the making of the Cuban revolution that I found utterly believable. Not just “take it to the bank” gripping, but levitational — for someone like myself it’s a kind of perfect dream movie.

It’s also politically vibrant and searing — tells the “Che truth,” doesn’t mince words, doesn’t give you any “movie moments” (and God bless it for that).

It’s what I’d hoped for all along and more. The tale is the tale, and it’s told straight and true. Benicio del Toro‘s Guevara portrayal can’t be called a “performance” as much as…I don’t know, some kind of knock-down, ass-kick reviving of the dead. Being, not “acting.”

I loved the lack of sentimentality in this thing, the electric sense that Soderbergh is providing a real semblance of what these two experiences — the successful Cuban revolution of ’57 and ’58, and the failed attempt to do the same in Boliva in ’67 — were actually like.

Oh, God…the second half is starting right now. The aspect ratio on the second film is 1.85 to 1, but the first film was in Scope 2.35 to 1.

Posted five and a half months later: Steven Soderbergh‘s Che shows tonight at the AFI Fest inside the big Chinese theatre, and I will be in attendance. This will be my third time and the honest-to-God truth is that I can’t wait to slip into it again. For me the Che experience is not unlike how Tom Wolfe once described the experience of settling into the Sunday New York Times — “that great public bath, that vat, that spa, that regional physiotherapy tank, that White Sulphur Springs, that Marienbad, that Ganges, that River Jordan for a million souls.”

Che, in other words, isn’t a pamphlet or a short story or tight three-act “movie” to be savored with a tub of popcorn and a “do it to me” attitude. It’s about luxurious feasting as long as you understand the kind of feast that it is. A big and filling one, certainly, in terms of realism and theme and transportation, but served without conventional “story”, patented emotionalism, movie moments, dessert, coffee, appetizers, waiters, napkins, brandy or any of your standard four-star restaurant perks.

Obviously I’m not mentioning Che‘s subject matter, cinematography, real-life history, performances, etc. I just can’t do it again. Not now anyway. I’ve written about it so many times it’s coming out of my ears.

Perhaps there is, in fact, some kind of positive counter-surge brewing among those who are not critics. In the same way that 2001: A Space Odyssey, dumped on by big-city critics when it opened in April 1968, was saved by doobie-tokers. By this I mean people with the apparent capacity to enjoy a film that doesn’t do “drama” and just roll with what it is and what it does.

For me this boils down to the savoring of naturalistic experience, behavior, aroma — a kind of high-end movie versimilitude trip that isn’t trying to arouse and soothe in a campfire-tale sort of way but is strangely immersive all the same.

“Che is a direct challenge to audiences,” declared L.A. Times guy Mark Olsen in a 10.31 article. “Depending on who you ask, Che is either Soderbergh’s greatest masterwork or his grandest folly.”

Che is so fully realized and so completely off on its own humid jungle trail that many don’t get what it’s doing. It is in no way a folly.

In the HuffPost piece, written last April, I wrote, “Hey, how about presenting the two films as a single, gargantuan Lawrence of Arabia-styled deal with an intermission, running between four or four and a half hours?” I was half-joking at the time.

I also wrote, “Given the indisputable fact that we are living in the most dumbed-down era of American moviegoing (certainly in terms of the mass audience) since the invention of the movie camera, how many popcorn-munchers are going to be willing, much less eager, to go four hours plus with Che Guevara? Especially given their reluctance to support even Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez‘s Grindhouse, a two-part, three-hour popcorn movie about hot women, zombies and car chases?”