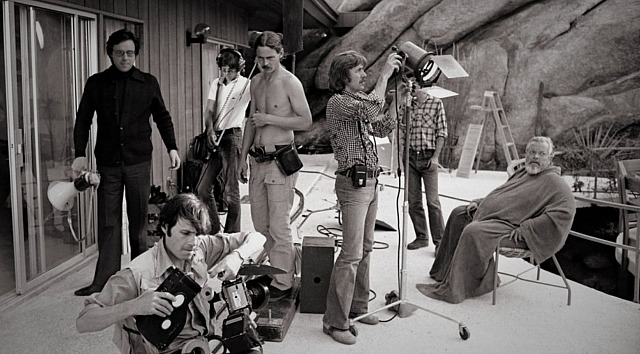

I saw Orson Welles‘ The Other Side of the Wind yesterday. It’s a bitter, cynical, sometimes darkly funny hodgepodge, an inside-new-Hollywood movie that was filmed on the fly between 1970 and ’75 in various formats, and a film that has a lot on its mind but has crawled so far up its own ass that the viewer can’t hope to enjoy much access.

It’s not a good film. Any film that makes you say “wait…what’s happening?” or “what was that line?” over and over is doing something wrong. It’s so damn spotty and splotchy. So scatter-gun, so haphazardly chop-chop and cut-cut. It never achieves a rhythm or a sense of flow-through or harmony of any kind. Within 10 or 15 minutes I was feeling exhausted.

It’s about an old craggy director named Jake Hannafort (John Huston) who sees himself as cut from the Ernest Hemingway cloth, and who’s just back from Europe and trying to find money to finish a film or start a new one or something along these lines. And so he throws a party in the desert and dozens attend — rivals, colleagues, managers, film critics, sycophants, students with cameras, wannabes, old friends.

Nobody ever seems to actually converse in an engaging, back-and-forth way. Nobody seems to listen to anyone else. It’s all bitter talk, fuck talk, belch…bitter talk, fuck talk, belch…bitter talk, fuck talk, belch…bitter talk, fuck talk, belch…bitter talk, fuck talk, belch, etc.

It would be one thing if everyone was improvising and Welles was gradually threading their material into some kind of half-assed narrative that delivered some kind of attitude or metaphorical mood, but everyone (and I mean especially the name-brand actors) is (a) “acting” and (b) obviously “speaking lines,” and it just doesn’t work.

Withered, craggy-faced Huston keeps puffing away on that cigar and regarding everyone with suspicion or disdain or a combination of both. Lili Palmer (a replacement for Marlene Dietrich) just sits around and says her lines in a deadpan way. Chubby-faced Peter Bogdanovich (playing a hot young director named Brooks Otterlake) says his lines with a tone of wry self-amusement. Susan Strasberg (a Pauline Kael stand-in) says her lines in a kind of needly, challenging way. Cameron Mitchell just hangs around and says his lines; ditto puffy-faced Edmond O’Brien. Paul Stewart says his lines in the usual Stewart way…seen it all, heard it all. Joe McBride says his lines with a certain sardonic edge. But I couldn’t latch onto anything or anyone. The film refuses to sink in.

Where is this going? What is there to learn or care about? Where is the soul of this film? Who wants to wade through this fucking mess of a movie? This is so inside-baseball I’m getting a headache.

Nothing really happens except that (a) everyone on the studio lot is invited to Jake’s party in the desert, (b) everyone arrives at the desert-house party and starts making sage, cutting remarks about this, that or another thing…yap-yappity-yap-yappity-yap-yap, (c) everyone becomes more and more drunk and cynical and despairing, (d) everyone heads for an outdoor drive-in to watch Jake’s movie, and then (e) Jake drives off in a Porsche and dies. (Except he does this at the very beginning, or before the beginning)

Robert Altman used to be so much better at this kind of thing — he would capture little snips and quips and cut away to this or that and somehow it would all fit together, but Orson’s film is so fucking “written out” and everyone is so determined to “act” (i.e., sell the moment, charm the audience) as well as radiate cynical or bitter or burnt-out or testy or pissed-off attitudes or feelings.

Does anyone in this film care about anything or anyone? I didn’t give a fuck about anyone or anything. At all. It really, really doesn’t work.

Read more