Pet Parakeet

Gary Marshall‘s Frankie and Johnny was released roughly 33 years ago, and I remember quite clearly never wanting to see it. I still don’t. Mainly because I don’t want to settle into a phoney conceit about the film’s glamorous, highly attractive costars who had played Mr. and Mrs. Tony Montana eight years earlier — Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer — living the pale lives of also-rans.

Terrence McNally‘s original 1987 off-Broadway play, Frankje and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, was about a pair of ordinary, middle-aged, worn-down homelies — F. Murray Abraham and Kathy Bates — falling in love within the grim confines of a studio apartme4=nt.

Critic after critic said Marshall’s version was too glammy — there was no way in hell anyone could accept that Pacino and Pfeiffer, aged 40 and 30 respectively, were schlubby, hand-to-mouth types, and that was all I needed to hear.

Movieline’s Stephen Farber: “Michelle Pfeiffer gives a very adept and winning performance in Frankie & Johnny, but she’s simply wrong for the part of a plain, world-weary waitress…anyone as gorgeous as she is has a lot more options than someone who looks like Kathy Bates (who originated the role on stage).”

Pacino fared no better with Washington Post critic Rita Kempley: “It’s just…well, imagine Kevin Costner as [Ernest Borgnine‘s] Marty.”

Casting the right actor or actress, in short, means never going too low or too high. Too much charm or physical attractiveness can throw a well-written, well-directed film out of whack.

How Will Trump’s Victory Affect Oscar Noms?

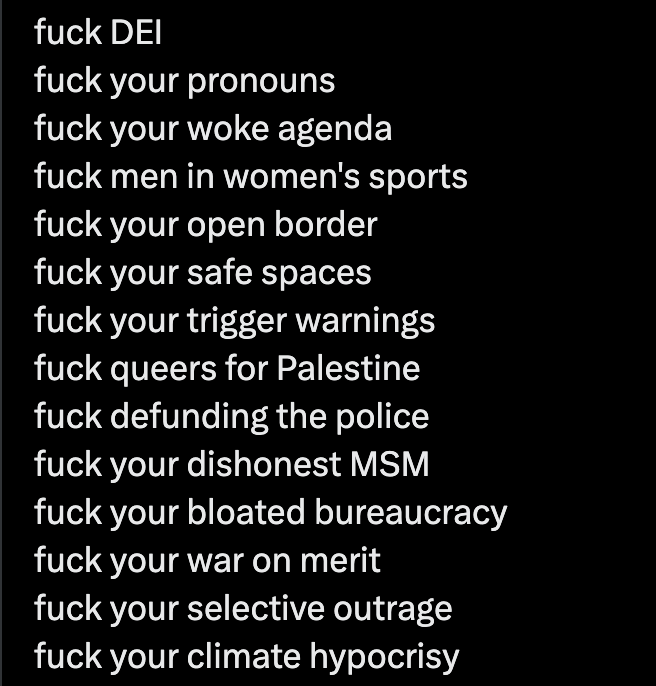

I’ll tell you how Trump’s victory affects the Oscars. The approvable but less-from-masterful Emilia Perez, a musical about a male Mexican drug baron transitioning into womanhood, will surge to the front of the Best Picture competition. Jamie Lee Curtis and all the other progressive, ardently-trans-supporting lefties will want to stand up and embrace Jacques Audiard‘s film as a statement of defiance against Trump dystopia.

In so doing, of course, Curtis and friends will also in effect be saying “eff you” to the 71.7 million Americans who voted for this animal. (As of Wednesday morning 66.8 million citizens, myself among them, had voted for Harris.)

In line with this, I also suspect that in the Best Actress race Emilia Perez‘s Karla Sofia Gascon will now elbow aside Anora‘s Mikey Madison…same empathy motive. Madison’s performance totally blows away Gascon’s, of course, but the Trump factor may change everything. For me one of the glories of Anora is that it’s not in the least bit woke.

I’m not aware of Trump having expressed disdain for transitioned adults (he’s only against susceptible minors being dragged into the cult) but the Jamie Lee Curtis brigade will want to express up-in-arms support for Gascon regardless. Variety‘s Clayton Davis will no doubt be urging this upon his readers.

I also think that more people will suddenly want to stream Ali Abassi‘s The Apprentice, a well-written, superbly acted drama about young Trump’s relationship with rightwing pitbull attorney Roy Cohn. If they have any respect for the grade-A artistry involved, they’ll certainly want to consider Best Picture and Best Director noms as well as a Best Supporting Actor nom for Jeremy Strong, at the very least.

I don’t want to give anything away, but there’s also…how to put this?…a sign-of-the-times, wokey, gender-fluid acceptance factor to be found in Conclave. Which should help it among the JLC “we all need to lock arms and tell Trump to go fuck himself” crowd. [Note: The Conclave thing has nothing to do with gender transitioning.)

If You Were A Pro-Trans Activist or Educator

…wouldn’t you be searching for tall grass right about now? I certainly would if I were in that camp.

I’m not in that camp, of course. As much as I despise Donald Trump and as much as I fear for the well-being of already-transitioned-and-just-living-their-lives trans folk, I think that Trump looking to make life difficult for academic or medical community pro-trans monsters (like those featured in Matt Walsh‘s What Is A Woman?) as well as trans-activist educators and pro-trans surgeons who have performed questionable gender-affirming bottom surgeries on minors…I’m not altogether unhappy that Trump feels this way about protecting vulnerable, susceptible minors from hormone blockers and gender-transition surgeries and whatnot, and will presumably act in concert with these views.

I’m sorry but I agree with some of this, partly because Trump’s attitude (he is not anti-trans as far as I know) and policies will probably help to protect my three-year-old granddaughter from trans activists within the educational, medical and social-activist communities. Maybe. I hope.

Posted by Forbes‘ Sara Dorn on 5.10.24: “Former President Donald Trump on Friday said he would undo a new Biden administration policy that will offer protections for transgender students under the Title IX federal civil rights law—his latest promise to restrict LGBTQ rights if elected to a second term.

“Trump said on ‘day one’ he would reverse the Biden administration’s expansion of Title IX that will prohibit federally funded schools from preventing transgender students from using bathrooms, locker rooms and pronouns that align with their gender identities.

@lexibunni.official #trans #transgirl #donaldtrumpisyourpresident #trump #2024election ♬ original sound – Lexi ️⚧️

“Trump told a crowd in Iowa in March he would sign an executive order to ‘cut federal funding” for schools pushing “critical race theory, transgender insanity, and other inappropriate racial, sexual, or political content on our children.’

“In January, he released a video [below] detailing a range of policies targeting gender-affirming care for minors, including pressing Congress to approve a federal ban and several measures to restrict federal funding when it came to trans issues.

“Trump said he would block doctors who provide gender-affirming care from Medicare and Medicaid, forbid federal agencies from actions to “promote the concept of sex and gender transition at any age,” and task the Justice Department with investigating the medical industry to see if they “deliberately covered up horrific long-term side effects of sex transitions in order to get rich.”

“In the video, Trump laid out additional plans for extending the restrictions to schools, promising ‘severe consequences,’ including potential civil rights violations, for educators who ‘suggest to a child they could be trapped in the wrong body.’

“In 2022 Trump told a crowd in Texas he would ban transgender individuals from competing in women’s sports, and attacked transgender swimmer Lia Thomas, weeks after her hotly debated record-breaking swim meet in Ohio while she was competing on the University of Pennsylvania swim team.”

America Chose The “Eating the Dogs and Cats” Guy

“There is a dark part of the American soul, and Donald Trump appeals to that…” — political strategist Chai Komanduri.

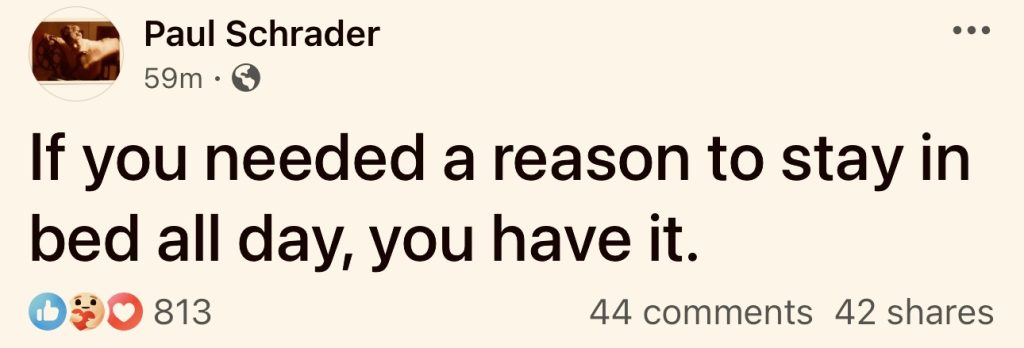

Faced with a choice between a sane, somewhat middling but far-from-dangerous ex-prosecutor with a good heart and a deranged, brain-fart, authoritarian criminal who cares only about himself, America chose the criminal. More than half of the country voted this way, and not by a whisker. It was a blow-out.

My Trump-supporting friends and family members excepted, I really hate last night’s majority mindset. I completely respect the process — it was a fair election — but I loathe the rank stupidity and the refutation of common sense that resulted in Trump’s victory. I’m not exaggerating here — I despise many of the progressive wokester things that Trump supporters despise, but voting to put that animal back into the White House was truly insane. It was a horribly destructive and nihilistic thing to do, and may God protect us all.

Will Democrats Be Into Nominating Another Woman For President in ’28?

Unfair as this sounds in the immediate wake of Kamala Harris‘s electoral tragedy, which marks the eighth anniversary of Hillary Clinton’s striking loss to The Very Same Beast, I’m presuming the Dems will not be especially keen on another female standard-bearer. Not in ’28, at least.

They need to nominate Gavin Elster, the San Francisco shipping tycoon…sorry, Gavin Newsom. You know he’ll be able to skillfully debate J.D. Vance, who will almost certainly be the 2028 Republican nominee. Face it — too many voters in this country are misogynist ayeholes. Plus Gavin is 6’3″. Plus he has three years to erase his overly-friendly-to-bums-and-thieves image.

Cathartic

She found out he was voting Trump pic.twitter.com/nM3C9delDY

— Concerned Citizen (@BGatesIsaPyscho) November 6, 2024

“I Was Right Here…”

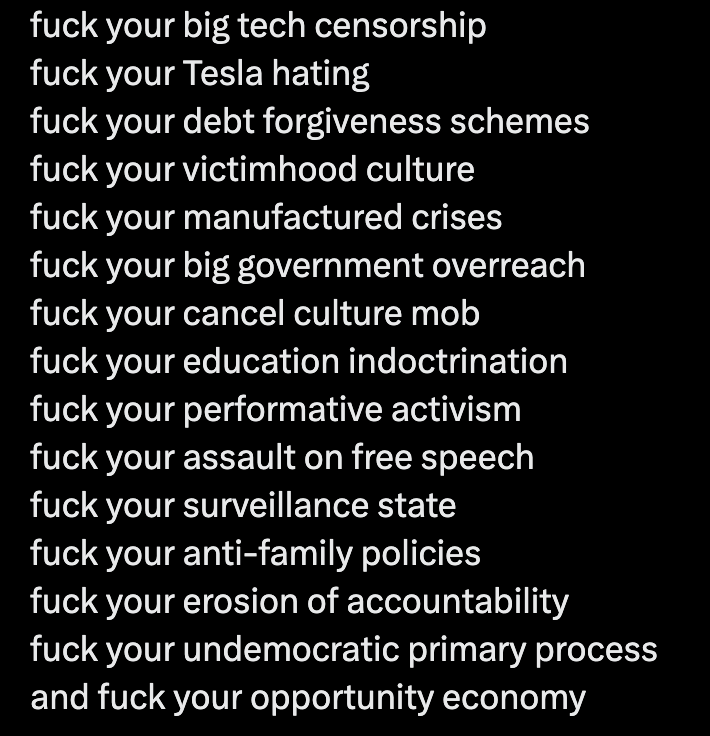

I am thoroughly ashamed and disgusted this morning. Ashamed to be a nominal citizen of a country that has re-elected an unmistakably dangerous, authoritarian-minded, foam-at-the-mouth criminal sociopath as president. I am catatonic. I am empty. I spit in the faces of the American hooligans who did this to us.

There is really and truly no common sense, no sanity, no elemental decency out there. Not in Bumblefuckland, I mean. We’re now so fucked I can’t even breathe, much less calculate. The temple walls are tumbling down around us. Sewer water is pouring into our lives.

Joe Biden was the principal architect of our doom by refusing to get out of the race until last July, and may that withered Irish banshee roast on a spit in hell for at least the next thousand years.

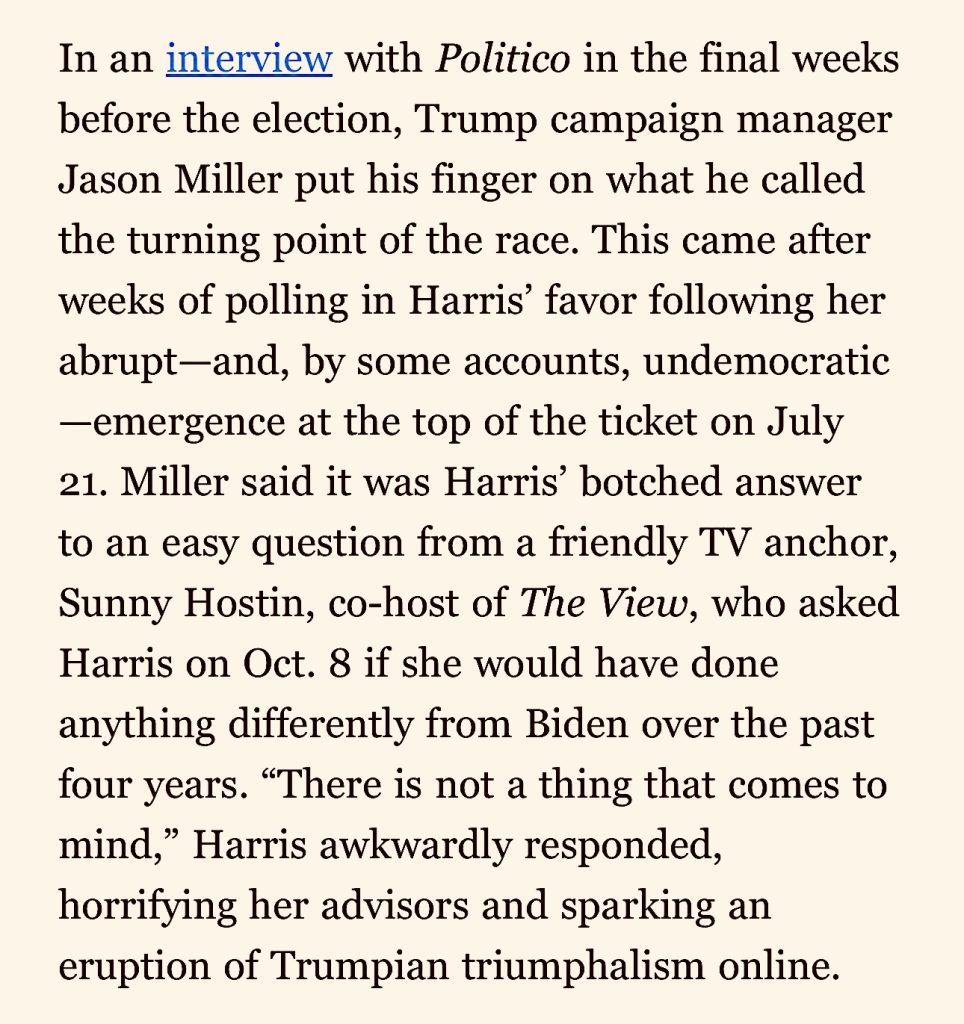

The sane and sensible (if admittedly somewhat mediocre) Kamala Harris ran a generally excellent campaign, but — be honest — she almost certainly torpedoed herself when she declined on “The View” to even partially throw Joe under the bus. That was beyond ridiculous. What was she thinking?

The disgruntled under-45 dudes whom progressive Democrats have identified as a proverbial social problem (including your Millennial-aged blacks and Latinos) have had their revenge, and the rural bumblefucks have won also. And the sensible, practical-minded blue urbans who were deeply, morally, logically and quite appropriately horrified by Donald Trump’s run-at-the-mouth candidacy simply didn’t have the horses.

We’re living in a sinking horror film right now. The obese, obviously declining Joker has won, the progressive loonies (including your career-cancelling wokesters and elementary school drag-show proponents) are shrieking in their bathrooms right now, and decent people everywhere are so stunned and doubled over they can’t even weep.

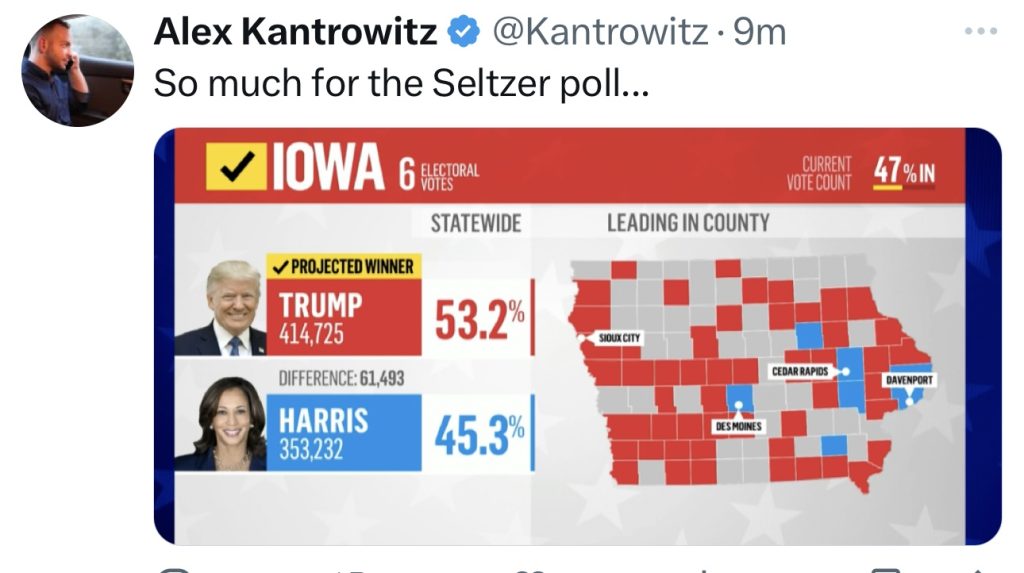

So many pollsters got it wrong once again.

The progressive pundits who wrote that enraged women (including white, older, Nikki Haley-supporting moderates) who were determined to reclaim control of their lives and bodies would save us…wrong.

The ugliness of the MSG fascist rally, the late-in-the-game shitshow that was going to decisively hand the presidency to Harris-Walz —- didn’t happen.

The floating island of garbage line apparently didn’t hurt Trump all that much — good God, it may have even helped him.

We’re really and truly The United States of Regressive Social Suicide right now. The ghost of John F. Kennedy still resides among us, and he is appalled. He is vomiting, dude.

Who are we? What are we? Dear God in heaven, I think we know the answer.

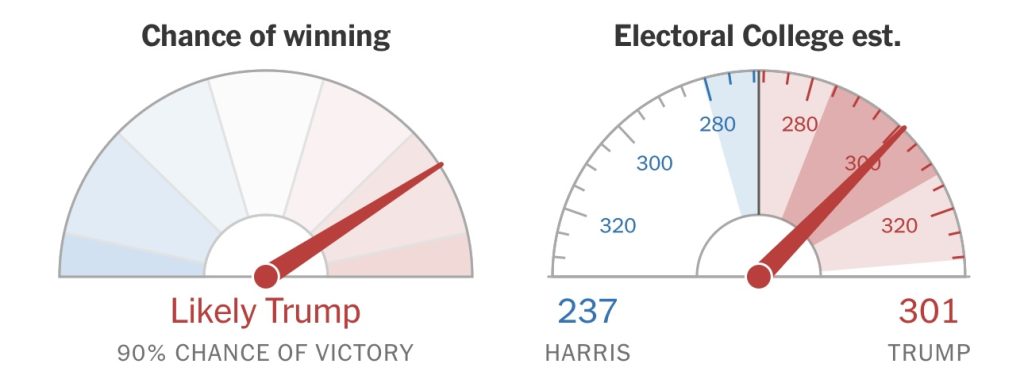

Dear God in Heaven…Harris Is Losing…It Might Be Over

11:50 pm: What an absolute tragedy. We’re all heading to hell. A louche, indecent, fascist-minded sociopath will be running the country between January ‘25 and January ‘29, and the damage to our democratic system will be considerable. Is there a chance Harris can eke out a win? Not much of one. She’s almost certainly lost. I feel so drained and deflated I can’t even cry.

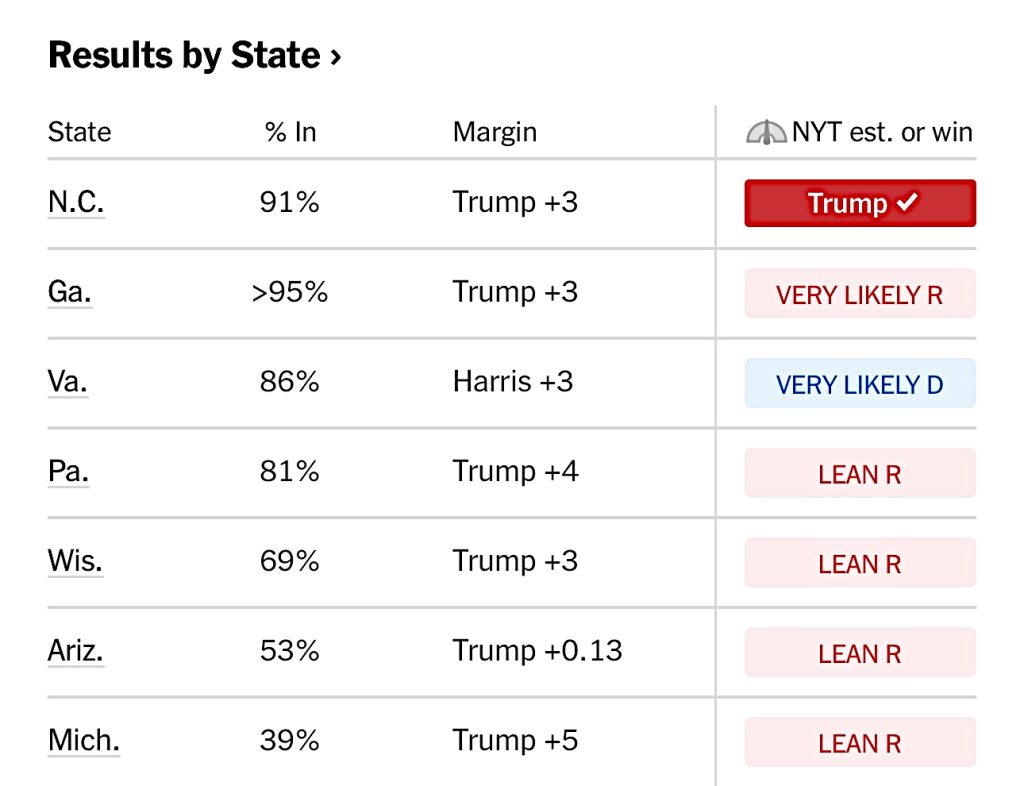

11:15 pm: Harris will probably lose Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, and that’s all she wrote. This is the beginning of a second national nightmare under Trump. I’m disgusted by the corroded moral values and lack of common sense among the rural voters who brought this about. I’m ashamed to call these degenerates fellow citizens. Good ole Joe Biden is back in the villain’s circle — he brought this about. If he’d bailed in late ‘23 or early ‘24 a better candidate might have emerged from a primary system. Thanks, Joe!! Remember how Frankie Pantangeli died in the bathtub at the end of The Godfather, Part II? Think it over!

10:37 pm: Trump is slightly ahead of Harris in Pennsylvania, and if he wins in the Buckeye state he’ll win the Presidency. The Pig Beast may actually bring about a second national tragedy! I’m devastated. But maybe Harris will eke out a slight Pennsylvania win…maybe. Please? But right now she’s also behind a point in Wisconsin. I feel weak, bruised. This is AWFUL.

10:26: Selzer got it wrong…booo!

10:16 pm: I’ve said all along that Harris would probably squeak through. Barely. That seems likely as we speak. I’ve been studying the returns for about three hours, but it feels like five or six. I’ve aged about three months. I’ve grown four or five new gray hairs.

10:04 pm: Decisive battleground numbers still not in…still hovering.

9:47 pm: Okay, Wisconsin is looking okay for Harris. Ditto Michigan, Pennsylvania. No longer freaking the fuck out, but I still don’t like this.

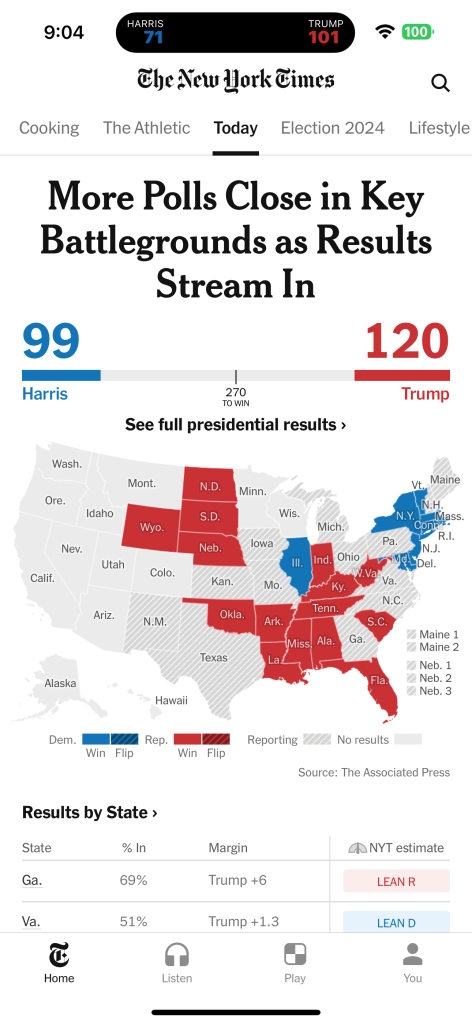

9:28 pm: Harris has won New York State…expected. Pennsylvania is looking good for Harris, but Wisconsin sort of isn’t. (Right now) What is this? I’ll tell you what it partly is — Harris and the progressive Democrat party has pretty much written off the dude vote, and right now they’re feeling the terrible result of that prejudice. That plus garden-variety misogyny, I’m thinking.

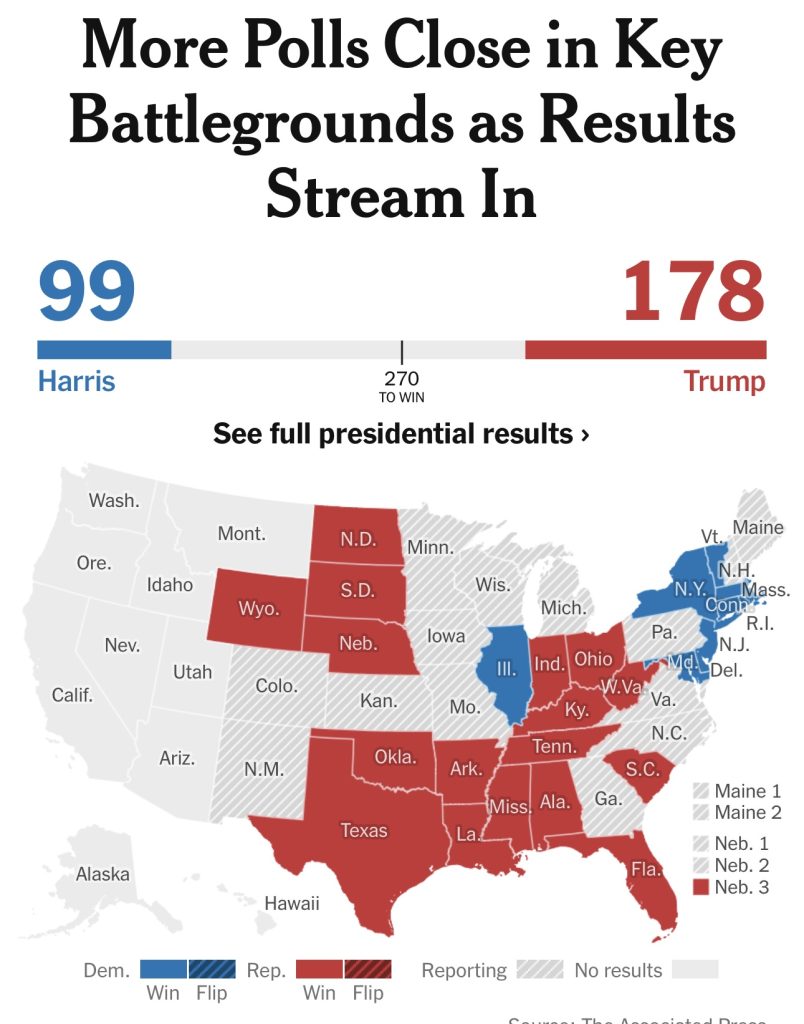

9:04 pm: Aacckk! Aaacckk! I’m so on edge about the drip-drip-drip uncertainty that I haven’t even felt the effect of that Oxy I dropped an hour ago. Harris isn’t pulling in votes like Biden did four years ago, and Trump is doing a little better than he did in ‘20. Trump is five points ahead in North Carolina…yeesh. Millions of people are knowingly voting for a monster. My stomach is flooded with acid.

8:48: I feel nothing but nerves, anxiety, tension. This is as close of a race as everyone has been predicting. No unexpected Harris surge…that’s for sure.

8:41 pm: How many days is this going to drag on? Will it be finally decided on Thursday or Friday?

8:36 pm: Florida independent voters have gone bigger for Trump this year than in ‘20. A concerning sign?

8:20 pm: Harris obviously isn’t going to prevail in Georgia. Oh, dear God…I feel so scared. All the usual patterns are kicking in, exactly as presumed. Bumblefuck states going for Trump, etc. I’m just not feeling the “phenomenal surge of women voters” thing. I’m scared, Auntie Em…I’m scared.

8:14 pm: Kirk Douglas in heaven: “Ladies and gentleman, there have been times when I’ve been ashamed to be a member of, for lack of a better term, whitebread American dude nation, and this is one such occasion.”