AMPAS Blues

Two days ago in a Gurus of Gold chat thread, a guy named Keil Shults observed that “[some of the Gurus] seem really determined to keep The King’s Speech at #1, despite all the evidence to the contrary.” And then a guy named movielocke explained the factors and the math. Reading it made me want to throw up, but he’s probably not wrong.

“Keil, it is simple math,” he said. “Inception, Social Network and Black Swan have lots of people [who] don’t like them. Toy Story has plenty of Academy members who will even refuse to see it because it is animated and therefore not a ‘real’ film. The Fighter has people who aren’t crazy about it and the director has a reputation for being a horrible person. The Kids Are All Right is gay and seems small in scope. Winter’s Bone and The Town don’t feel like real winners.

“But what really matters is that the voting for Best Picture is Instant Runoff. That means you do NOT win by being the most popular. You win by a combination of two factors — (a) Being well liked enough to last through the first five rounds of vote elimination, and (b) Being well liked enough so that on average you have a higher vote than the other film.

“The math says that no divisive film will never ever win Best Picture, unless there is a year where only divisive films are nominated.

“Every year that instant runoff is used, the film that wins will be the film that the vast majority of academy members just cannot vote lower than 5th. Last year that movie was The Hurt Locker.

“This year, The Hurt Locker slot movie is The King’s Speech. No one will actively dislike the movie enough to vote it lower than sixth, so it is pretty much mathematically impossible that The King’s Speech will lose. Unless a concerted campaign is made to educate Academy members to vote strategically [in order to] vote The King’s Speech down.”

Texas Know-How

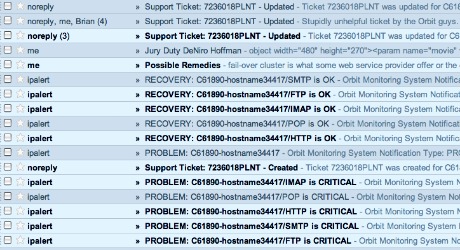

The tech staffers at Softlayer and Orbit The Planet have screwed up the server clock twice in the last seven days, and thereby caused all kinds of reader-posting issues. The site crashed early this morning due to what they said was an “overload.” (Nonsensical.) When they restored service they reset the server clock to nearly three days in the future. When I informed them of this they went “oh” and reset to the correct date and time. But this created another problem.

That’s because between now and late Monday night, all new HE posts (including this one) are going to appear before — i.e., below — the six stories I posted this morning between roughly 7 am and noon. Until I figure something out, I mean. And many of the comments relating to the top six posts (“Weekend Reading” to “Same Foxhole”) won’t show up either because they’re dated as 12.21 and 12.22 posts, and now that the clock is back to the correct date (12.18) and time the system will disregard any comments that are posted before the 12.21 and 12.22 time stamps.

The Softlayer/Orbit guys, in short, are awful — absolutely the slowest, most dull-witted, least problem-attuned donkeys I’ve ever dealt with in my six-plus years of dealing with internet service providers. Softlayer/Orbit is a technical tinderbox. What new problem will happen next?

No Thanks

I never order cheesecake, never buy it in bakeries, etc. A friend pushed a slice on me a few weeks ago and I relented but otherwise, no way. The closest I get is (a) occasionally thinking about it and (b) taking shots like this from time to time.

Mood Box

I haven’t had a nice little music box…ever. This is really very sweet. Real wood, smooth veneer, real simulated velvet. Thanks, Fox Searchlight! But I have to confess that the mirror came loose almost immediately, and that I had to stick it on with Shoegoo.

Film Comment Picks 'Em

The Film Comment/Film Society of Lincoln Center cool kidz have selected their Best of 2010 list, and the #1 with a bullet is Olivier Assayas‘ Carlos. I have to say that I agree with almost all…well, many of their choices. David Fincher‘s The Social Network is #2, followed by Claire Denis‘ White Material, Roman Polanski‘s The Ghost Writer, Jacques Audiard‘s A Prophet, Debra Granik‘s Winter’s Bone, Charles Ferguson‘s Inside Job, Alain Resnais‘ Wild Grass, Marden Ade‘s Everyone Else, and Noah Baumbach‘s Greenberg.

The FSLC list actually encompasses 50 films. Black Swan is ranked in 24th place. Inception came in 30th, Exit Through The Gift Shop made it to position #33, Animal Kingdom is ranked 35th, True Grit is 42nd, The King’s Speech is ranked 44th and Blue Valentine came in at 47th place. Congratulations, Derek Cianfrance — three positions way from dead last!

“More than 100 participants” took part in the poll, the release says. They included Thom Andersen (CalArts professor and filmmaker), Richard Brody (The New Yorker), David Edelstein (New York magazine), Scott Foundas (Senior Programmer, Film Society Lincoln Center), Larry Gross (screenwriter), Molly Haskell (author, From Reverence to Rape: the Treatment of Women in the Movies), Kent Jones (filmmaker, A Letter to Elia), Glenn Kenny (MSN Movies), Robert Koehler (Daily Variety and film festival programmer), Todd McCarthy (Hollywood Reporter), Don McMahon (Artforum), Paul Schrader (filmmaker, Adam Resurrected), Andrew Sarris, Amy Taubin (Sight & Sound) and Kenneth Turan (Los Angeles Times).

17 Extra Minutes

For what it’s worth, I’d pay good money to see the recently discovered 17 minutes of footage that was cut 42 years ago from Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Or rather, the 2001 footage that’s being described by Douglas Trumbull as “recently discovered.” Because it hasn’t been.

The 17 minutes of footage has been siting in a salt-mine vault in Hutchinson, Kansas, for eons, I’m told, and its existence was confirmed 20 years ago through the checking of inventory records by film restorer Robert Harris, who’d been asked to check on the 2001 elements by Kubrick.

A lot of the footage, I’m told, is floating-in-space stuff — superfluous, better left trimmed. A portion of it is from the “Dawn of Man” sequence. Apes hopping around, nothing all that special. Some shots of Gary Lockwood‘s Frank Poole character jogging in the centrifuge were removed along with shots of his space walk before HAL kills him. A scene showing HAL severing radio communication between the Discovery and Poole’s pod. Fatty extraneous stuff, in short, that made 2001 better by being taken out.

Would it be interesting to see this footage on a Bluray? Sure. Would 2001 seem like a better or somehow stronger film if the 17 minutes was re-integrated into the 139-minute released version? Probably not. It would most likely make the film seem flabby and longer than it needs to be. Would it be commercial if they put it out on Bluray? Oh, yeah. Because guys like me would pay through the nose to own it.

Brave Messenger

It’s obvious that Today‘s Matt Lauer doesn’t approve of controversial WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. That or he’s terrified of seeming in any way cordial, lest he be interpreted as being mildly okay with what Assange has been doing.

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

I think Assange is more than okay, actually. I think what he’s revealed is righteous, and that Michael Moore and Larry Flynt are good guys for contributing to his defense fund.

I’m also having trouble understanding how anyone can take seriously those charges that Assange raped and molested two women. It sounds to me like a sliver of a thin beef — it basically boils down to his not stopping when a condom broke. But it’s all the Swedish government has, and they’re being pressured to get him any way they can.

Then and Now

The more I think about the differences between James L Brooks‘ How Do You Know and Broadcast News, the more I shake my head in amazement. How could the same guy have directed and written something so smart and true 23-plus years ago and then make two 21st Century flops in a row, Spanglish and now this thing?

Movie Videos & Movie Scenes at MOVIECLIPS.com

Obviously Brooks, 70, isn’t the same guy today as he was when he researched, wrote and directed Broadcast News, when he was in his mid to late 40s. It sounds cruel to say stuff like this, but most creative types experience peak periods of 10 or 20 years, and then they step off the treadmill. They go soft, age out, lose the mojo. Francis Coppola went through this syndrome. Vigor, vitality and being attuned to the culture don’t come easily at any age, but it’s really tough for older wealthy guys to hang on to it.

I only know that there isn’t a single scene in How Do You Know that’s nearly as good as the one above, and this is a relatively minor moment in Broadcast News . But the way Jack Nicholson slowly turns around and looks at the bespectacled news chief when the latter suggests that Nicholson could save a few newsroom colleagues from unemployment if “you knock a million or so off your salary” is classic.

The thing you just can’t buy in How Do You Know is Reese Witherspoon‘s interest in Owen Wilson‘s big-league pitcher, who’s obviously immature, selfish, a dog and more than a bit of an asshole. Wilson is such an absurdly bad boyfriend choice that Witherspoon’s decision to not only slam ham with the guy but move into his place kills whatever respect and/or empathy the audience might have had for her to begin with.

As I wrote on 12.9, How Do You Know “has some lines and little moments that work very nicely. It’s not my idea of a disaster — I can foresee a portion of the critics saying it’s okay — but my main impression was that of a very bizarre, strangely un-life-like film. The writing is simultaneously clever and constipated, and the lighting and the cinematography seem overly poised and prettified. It looks and feels like it’s happening in some kind of Hollywood fairyland that feels a lot like a sound-stage set (i.e., one that’s meant to simulate certain indoor settings in and around Washington, D.C.).

“It seems as if Brooks has entered his formalist, out-of-time, older-director phase. The look and tone and pacing of How Do You Know reminded me of the look and tone and pacing of Alfred Hitchcock‘s films after The Birds — the increasingly rigid and old-fogey-behind-the-camera feeling of Marnie, Torn Curtain, Topaz, Family Plot, etc. (Some believe that Frenzy was an exception; I don’t.) I’m talking about a phase in which a director is not only repeating the kind of brush strokes that felt fresher and less constipated 20, 25 or 30 years earlier, but emphasizing them so as to say ‘I know this may seem unnatural to some of you out there, but this is how I like to do things, no matter how stylistically out-of-touch this film may seem. This is me, take it or leave it.'”

One reason I feel that Witherspoon’s relationship with Wilson is difficult to swallow is that you don’t believe her character would have hot sex with anyone. That’s because Reese Witherspoon has never seemed believable as a naturally sexual being. To me, anyway.

Just as it’s difficult not to have erotic or sexual thoughts about certain actors and actresses, there are actors and actresses on the other side of the spectrum who seem antithetical to any kind of erotic allure or activity. You not only find it difficult to believe in their characters as sexual beings, but they themselves seem anti-sexual — the idea of any kind of physical intimacy seems unlikely or misguided or ill-considered. There are many, many actors and actresses who fall under the latter category (I always avoided any thoughts of John Candy having sex back in the ’80s), but How Do You Know convinced me that Reese Witherspoon is one of those no-sex-we’re-British types. And that’s fine. Not everyone is obliged to radiate smoldering hotness. It takes all sorts.

Puttin' On Da Ritz

Yesterday Oscar co-host Anne Hathaway and the show’s co-producer Bruce Cohen told the school choir for PS 22 — an elementary school in Flushing, Queens — that they’ll be taking the choir to Los Angeles to perform at the Academy Awards on 2.27. 40 cute kids singing on-stage at the Kodak…cool. But why? What’s the connection?

It’s obviously Cohen’s idea because he’s the one stirring the kids up and introducing Hathaway, etc. Did Cohen attend PS 22 as a kid or something? Flying out 40 kids plus a teacher or two plus a chaperone for each kid plus hotels and transportation and meals — that’s a lot of dough to spend ($200,000? 90 to 100 people x how much per person?) for a single musical sequence that’ll be nice to see and hear but — let’s face it — isn’t going to matter all that much to 99% of the viewing audience.

I’m sorry but Cohen just seems like a second-rate Alan Carr type — glamour and tinsel, a gladhander. He and his co-producer Don Mischer both seem this way. One of their first moves was to try and re-hire Hugh Jackman as host (and what, have him sing “Top Hat”?). Their subsequent decision to have Hathaway and James Franco co-host struck most discerning observers as an odd call, to put it politely. I’m just getting all these indications that the Oscar telecast is going to be wildly low-rent in some way.

Update: I realize that for some, these kids are considered a huge YouTube sensation with millions and millions of hits, and that they do covers of songs, etc.

Scolding Is Justified

I have my Lesley Manville obsession, and TheWrap’s Steve Pond has a thing about Javier Bardem‘s performance in Biutiful. I feel the same way, actually, as does Ben Affleck and Entertainment Weekly‘s Dave Karger and Ryan Gosling, Sean Penn, Guillermo del Toro, et.al. Here’s how Pond puts it:

“Every awards season is rife with injustices, but one in particular stands out so far this year. Javier Bardem’s performance in Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu‘s haunted, crushing tone poem Biutiful is a towering achievement, a magnificent performance that should comfortably sit on every list of the great acting accomplishments of the year.

“Without saying much – Jesse Eisenberg likely spouts more words in the opening three minutes of The Social Network than Bardem does in the whole of Biutiful — Bardem subtly evokes and embodies a world-weary Everyman living with a ticking clock and the weight of the world on his shoulders.

“Guillermo del Toro has called Bardem’s performance ‘monumental’; Sean Penn said it’s the best thing he’s seen since Marlon Brando in Last Tango in Paris.

“When I saw King’s Speech, I thought Colin Firth gave the best performance I’d seen in a couple of years,” Ben Affleck told me at a party for The Town a couple of weeks ago. “Then I saw Biutiful.” He shook his head. “Javier is on another level from the rest of us.”

“Memo to Academy members: SAG and Globe voters blew it, badly. Don’t you do the same.”

All these admirers plus the jury at last May’s Cannes Film Festival had no problem seeing Biutiful and recognizing what they’d seen in Bardem’s performance. But this kind of thing, let’s face it, doesn’t play as well with Average Joes. Many if not most American moviegoers (including film industry types) are simply too grief-averse — too married to the idea of a movie lifting your spirits or acting like some kind of friendly quaalude — to summon the character to see Biutiful. Can we be honest? Can we call a spade a spade? “Grief averse” is a polite way of saying “too shallow.”

Good Taste

The Chicago Film Critics Association had the good taste and sound judgment to hand Another Year‘s Lesley Manville one of their five Best Actress nominations, so backslaps and “howdy hey” for that. Otherwise they gave eight nominations to David Fincher‘s The Social Network — Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor, etc. — and six noms each to Black Swan, The King’s Speech, Winter’s Bone and True Grit.

The final round of voting for the CFCA awards will conclude at 5:00 pm Central on Sunday, 12.19. The winners will be announced on the morning of Monday, 12.20.

Blue Valentine‘s Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams were nominated for Best Actor and Best Actress, respectively, and both Amy Adams and Melissa Leo were nominated for Best Supporting Actress for their performances in The Fighter.

Hey, what about Mother‘s Kim Hye-Ja and A Prophet‘s Niels Arestrup?