One of the best analysis pieces I’ve ever posted to this column (and we’re talking literally thousands of items and stories since HE’s August 2004 launch) was my High Noon vs. Rio Bravo thing, which I wrote about three years ago. I’m very proud of having made it clear to God and Peter Bogdanovich and Quentin Tarantino and all the other Bravo cultists out there why I feel Howard Hawks‘ 1959 film has, okay, some merit (it’s a half-decent film) but doesn’t hold a candle to Fred Zinneman‘s 1952 classic.

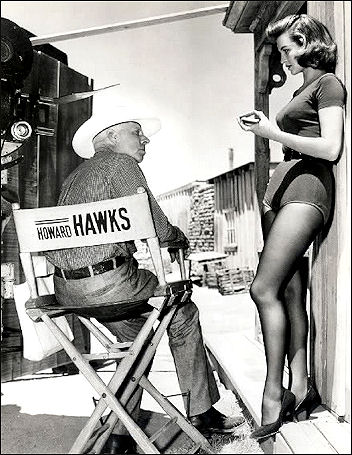

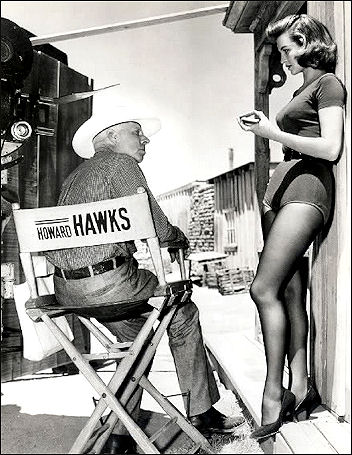

Howard Hawks had to know that making a romantic couple out of the hulking 51 year-old John Wayne and the doe-like, rail-thin 26 year-old Angie Dickinson was ludicrous, but I think he hired her anyway because of her great gams. And I think she knew this.

I just re-read the article and man, it really feels good when you discover that a semi-oldie reads clean and straight and true.

But in reading another well-written Rio Bravo analysis piece — actually a Rio Bravo vs. El Dorado thing, written a year ago by G.A. de Forest — it hit me that my ’07 article overlooked a huge aspect of Rio Bravo history, which is that Hawks more or less remade it twice — as El Dorado and Rio Lobo.

And so the obvious question: how good or classic or what-have-you can Rio Bravo be if the director not only decided five or six years later that he could improve upon it, but acted upon this notion not once but twice (with remakes #2 and #3 only four years apart), and using the same lead actor (John Wayne) in all three versions? And then admitting later on that the third version was shite?

Did Fred Zinneman feel the need to remake High Noon? Not as far as I know. We know for sure that he never did. Could it be that Zinneman felt it was good enough and didn’t need an upgrade? Uhm, probably. Does anyone think there might have been a reason why Hawks felt a need to remake Rio Bravo twice? I’m just spitballing, but the obvious conclusion is that he simply didn’t think Rio Bravo was “good enough,” to borrow from the Hawks lexicon.

“Rio Bravo, for ill-defined reasons, is the more generally admired by critics,” de Forest wrote. “Hawks specifically remade it because he believed he could improve on the first version, and then believed he had. I too, maybe because [I’m] a child of the Sixties, have always preferred El Dorado, though having just seen Rio Bravo again and giving it proper attention, I appreciate its niceties more than before.

“Hawks knew what he was doing in remaking it…[and] by most measures El Dorado is a less compromised piece of filmmaking. Maybe simply to give the ensemble cast more on-screen time, there is a conscious insert in Rio Bravo where singing stars Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson get to do their thing — Dean crooning a cowboy song — ‘My Rifle, My Pony, and Me’ — with less C & W feel than anyone since Roy Rogers. Ricky bats his thick eyelashes and heavy lids for the girls rather irritatingly throughout, and almost pouts his more-generous-than-Elvis lips. Walter Brennan comes close to self-parody with his incessant cackling.

“On top of this, the original is far too wordy, especially for a western — courtesy of the screenplay by highly cultured Hawks favorites Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett.”

I really think this settles it once and for all. All those Bravo groupies need to stand up, man up and explain clearly and concisely how a film that its own director felt a need to remake twice is somehow superior to a single, stand-alone western that its co-creator (the other being Carl Foreman) never re-thought or re-made. Because it can’t be done. I knew about the remakes all along, of course, but now that I’ve re-thought everything and re-read the ’07 article and jumbled it all around, I now feel — in my own mind, at least — that the High Noon vs. Rio Bravo debate is over and done with, and the bitches have scattered.