The one sterling asset in Clint Eastwood‘s Invictus is…actually, make that two sterling assets. One is the fact that Eastwood is Eastwood and that there’s something I love about sinking into his films, even when they’re not double-grade-A. The other is Morgan Freeman‘s performance as Nelson Mandela — a thing that will carry Invictus along with ticket buyers and probably reap Oscar glory.

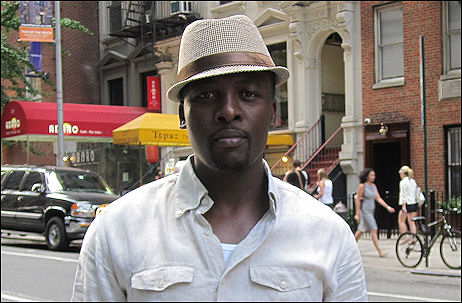

Morgan Freeman in Clint Eastwood’s Invictus

Freeman’s performance is not a deep-mine thing or a dazzling revisiting of a still living-legend whose face and manner are well remembered by millions. But it’s really quite satisfying — soothing — to watch Freeman, nearly a dead ringer, adopt a slight accent and step into Mandela’s shoes and walk around with a slight stoop and a faint grin and radiate that serene wise-man thing.

There’s no question Freeman will end up as one of the five Best Actor nominees, and I’m betting right now that he’ll win. He’s obviously playing a more stirring and inspirational guy than George Clooney‘s Up In The Air traveller, and a more sympathetic and charismatic figure than Daniel Day Lewis‘s Guido in Nine. He’s dealing with the same sort of historical turf that Christopher Plummer stands on in The Last Station, but Freeman has better lines and a stronger spirit.

His toughest competitors are A Single Man‘s Colin Firth, The Hurt Locker‘s Jeremy Renner and A Serious Man‘s Michael Stuhlbarg. But we all suspect that two out of these three are facing uphill odds, under-valued as they currently are by go-along pundits.

Otherwise Invictus has problems, but not ones that involve what it is. The problems it has are about what people are expecting it to be.

Invictus is a nice, cleanly told, mildly stirring South African sports film that should have been released in the late spring or early summer. Because if it had been it wouldn’t have all this weight on it. It could have been directed by Roger Donaldson, and I don’t mean that as a put-down to Donaldson or Eastwood. It just is what it is, but the fact that it’s the latest Eastwood film with a December opening has everyone hot and bothered. Well, cool down.

Invictus does remind us of what a centered and wise and very cool guy Mandela was — it gives off a contact high in this respect. But it’s all exposition, exposition, exposition and more exposition. And there’s almost no “story” in the sense that there are no character turns, no twists, no nothing in the way of surprises or intensifications. A good amount of it — most of it, really — is about South African government employees watching rugby games or standing around offices or sitting on buses or in the backs of cars or watching TV. (TV screens get a major workout in this film.) Or about athletes jogging and playing rugby and working out.

Invictus is about an “important” subject — one we should think about and perhaps learn from — but it mainly just ambles along. It kinda gets off the ground at the end, but rousing sports-movie finales don’t travel like they used to because we’ve seen them so damn often. You can’t just have the good-guy team win and show everybody cheering. That’s not enough any more.

This is one reason why Invictus doesn’t really go “wow” or “kaboom.” It’s fine and very agreeable in some respects. Anyone who writes in and says “You’re wrong” or “I loved it!” will not get put down in this corner. But there’s no getting around the fact (and it pains me to say this, being a major fan of Unforgiven, Play Misty For Me, High Plains Drifter, Breezy, Million Dollar Baby and Gran Torino) that Invictus is second-tier Eastwood.

Freeman and the take-it-easy, don’t-push-it quality to Clint’s direction are two winning elements. But it should have been a more layered thing. On one level there would have been what we have now — an above-board, what-you-see-is-what-you-get story about how a rugby team and a championship game helped bring a divided nation closer together. And there also would have also been…something else. A more penetrating look at the travails and fears of Mandela or Matt Damon‘s Francois Peinaar. A parallel story, a powerful subplot, a more prominent undercurrent or some other big thematic echo. Something.

Morgan Freeman, Matt Damon

The first half-hour is the best part, by far. Freeman’s manner and personality are quite winning, and I was particularly impressed by a scene in which he gives a low-key address to some white staffers who are presuming they’ll be fired by the new Mandela administration. There’s also a good moment as the film begins in which we’re shown a white high-school rugby team practicing behind a chain-link fence and some young black kids playing rugby in the lot across the street, and the way they react differently when Mandela’s little motorcade drives by. All of this early stuff is quite good.

But once the rugby-championship element kicks in Invictus starts to flatten out and restrict itself to lateral passing back and forth. People said that Martin Scorsese‘s The Age of Innocence was a movie about cufflinks. And that Anthony Minghella‘s Cold Mountain was about a man walking through the woods. Boiled down, Invictus is (after the first half-hour) about people watching TVs, watching the rugby team play in a stadium, talking about what they’re seeing or thinking, and commenting on what may or may not happen.

And feeling exhilaration, of course, when the Big Game finally happens and (spoiler! happened 14 years ago!) South Africa beats New Zealand. That’s all it really is.

I almost admire Eastwood for keeping it as simple and straightforward as it is. It’s nice to see restraint and centeredness in a director, and there’s something very elegant about the way he steers Invictus along at 35 mph without cranking things up for the sake of cranking things up.

I know, I know — a satisfying plate of pasta doesn’t have to be “brilliant.” It just has to be carefully prepared and well seasoned and made with love. Invictus is a very pleasant and mildly stirring bowl of fettucini with a highly agreeable lead performance by Freeman. But it’s not one of those ratatouille dishes that win awards and inspire raves from restaurant critics.