In one of her best-written reviews in a long while, Variety‘s Leslie Felperin calls Werner Herzog‘s My Son, My Son What Have Ye Done? “something of a shaggy-dog story whose bark is more interesting than its bite.” By this she means that “the main action is interspersed with lots of wacky, hardly necessary but occasionally amusing digressions,” and that savoring these is more than half the meal.

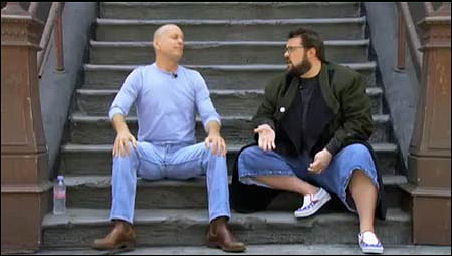

Michael Shannon (l.), Willem Dafoe (r.) in Werner Herzog’s

My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?“If My Son were an album,” Felperin declares, “it would be a concert of Herzog singing a collection of his reworked B-sides, live and slightly off-key.

These digressions include “an inexplicable visit to what looks like Inner Mongolia; a trip to the Peruvian wilds that visually evokes Herzog’s Latin American-set classics Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo; and a visit to an ostrich farm run by a deranged character played by The Wild Blue Yonder‘s Brad Dourif.

“The story proper opens with San Diego homicide detective Hank Havenhurst (Willem Dafoe) arriving at a suburban manse to investigate the murder of Mrs. McCullum (Grace Zabriskie). The elderly matron was skewered with a sword by her own son, Brad (Michael Shannon), in the home of her neighbors (Irma P. Hall, Loretta Devine), witnesses to the event.

“Havenhurst hasn’t got far to go to look for Brad: He’s holed up in his own house across the street with a shotgun and two hostages, whose identities are only revealed in the last reel. Police surround the house to wait it out. Brad’s g.f., Ingrid (Chloe Sevigny), arrives on the scene and tells Havenhurst about the slow unraveling of Brad’s mind, beginning with a misbegotten trip to Peru, when he started hearing voices in his head.

“The testimony of legit helmer Lee Meyers (Udo Kier) further fills out the story, as he explains how Brad started overidentifying with his role as the mother-slaying Orestes in a stage production of The Furies, while at home, he struggled to separate himself from his over-protective, emotionally smothering mom.

(l. to r.) Grace Zabriskie, Shannon, Chloe Sevigny

“From nearly every character Klaus Kinski played for the helmer through the many eccentrics featured in his docus and right up to Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man, Brad is the latest in a long line of Herzog protagonists a few sandwiches shy of a picnic,” Felperin writes.

“One rather warms to him when he channels Herzog with an anti-hippie rant — ‘Stop meditating! Come up with a coherent argument!’ — in the Peruvian interlude, but despite the innate charisma Shannon, with his Andean-range-long stare, brings to the role, his schizophrenic Brad simply isn’t all that interesting.

“Pic’s other characters are not a particularly compelling bunch, which is even more disappointing given that they’re played by some pretty big names. Dafoe, Sevigny and Kier seem to be competing to see who can give the most arch, knowingly flat perf, putting invisible air quotes around their renditions of ‘normal’ suburbanites. David Lynch regular Zabriskie (Inland Empire), on the other hand, hams it up royally, particularly in a scene in which she smiles creepily at Brad and Ingrid for what seems like a full minute of screen time.

“In fact, at times the pic feels like a joshing, good-natured parody of a Lynch movie, given the big deal made of coffee in one scene, the use of spooky underlighting and the comical, nonsensical appearance of a person of restricted growth (Verne Troyer). Of course, Herzog arguably got there first with the creepy little people in Even Dwarfs Started Small. In any event, Lynch is definitely in on the joke; he exec produced the pic, which is billed as ‘a David Lynch presentation.'”