If you liked Hearts of Darkness, Fax Bahr and George Hickenlooper‘s renowned 1991 documentary about the arduous making of Francis Coppola‘s Apocalypse Now, you may also have a place in your head for Coda: Thirty Years Later, an informal sequel to Hearts of Darkness that is “partially” about Coppola filming Youth Without Youth in Romania two years ago.

Peter Nellhaus‘s Green Cine Daily report on the doc, which Nellhaus saw Sunday night at Miami’s Colony theatre, has a lot of good reporting, including a remark that “much of the footage shown from Youth Without Youth is bathed in golden browns” and another that “visually, [Coppola’s] new film will remind some of the first two Godfather films.”

“The prime difference between Hearts of Darkness and Coda,” Nellhaus observes, “is that Apocalypse Now was filmed in desperate circumstances, while Coppola’s profitable wine business now allows for him to return to filmmaking on his own terms.”

In other words, the newer doc is going to be less interesting because it’s about filmmaking with a certain comfort factor, which means it obviously won’t have the grueling real-life drama that made Hearts of Darkness such a fascinating ride. Pressure and desperate circumstances are obviously difficult things to live through, but they pay off like a slot machine when they’re part of a documentary.

AmPav panels

It’s a tough job lining up discussion panels at the American Pavillion during the Cannes Film Festival, since talent usually only flies into Cannes for brief 24-hour periods (the barrage of invasive paparazzi attention is soul-deflating) and their publicists are always first and foremost hooking them up with major media outlets, with AmPav panels often regarded as a low priority. Roger Durling, director of the Santa Barbara Film Festival, has nontheless rounded up My Blueberry Nights director Wong Kar Wai, Sicko director Michael Moore, Mister Lonely director Harmony Korine and New Line honchos Robert Shaye and Michael Lynne to talk about New Line’s 40th anniversary.

Telluride and “Youth”?

Pete Hammond doesn’t think that recent announcement about Francis Coppola‘s Youth Without Youth having its world premiere at the RomaCinemaFest in late October necessarily means that it won’t show up at Telluride Film Festival a month and a half earlier. “Telluride doesn’t advertise its films in advance and gets movies all the time before their official ‘world premieres’ at Toronto or other places because of that reason,” he reminded me yesterday. “To call something a ‘world premiere’ means nothing to Telluride, which just wants to show good movies. Brokeback Mountain premiered at both Venice and Telluride at the exact same hour a couple of years ago even though Venice had it billed as a world premiere.”

Ordinary people vs. classics

There’s an interesting idea for a series of N.Y. Times articles suggested by Michael Wilson‘s 5.13.07 piece about a New York cop in his 60s watching Jules Dassin‘s The Naked City for the first time. Sit down and watch a classic film with an average, not-terribly-sophisticated person and report his/her reactions. I sincerely love this idea, which would basically deliver downmarket versions of those articles from three or four years ago in which big-name directors watched their favorite films (i.e., Woody Allen getting all sentimental over Shane). Think of it — Shawna Castro of Livingston responds to F.W. Murnau‘s Sunrise, Fred Collard of Mobile considers Michelangelo Antonioni‘s L’Avventura, and so on. Are classic films only for the ivory-tower elites or do they have the power to affect Average Joes?

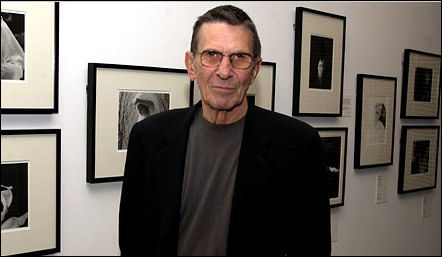

Nimoy’s chubby-chasing

“The average American woman, according to articles I’ve read, weighs 25 percent more than the models who are showing the clothes they are being sold,” Leonard Nimoy has told N.Y. Times writer Abby Ellin for a profile of him and his photographs of obese women. “So, most women will not be able to look like those models. But they’re being presented with clothes, cosmetics, surgery, diet pills, diet programs, therapy, with the idea that they can aspire to look like those people.

“It’s a big, big industry,” Nimoy goes on. “Billions of dollars. And the cruelest part of it is that these women are being told, ‘You don’t look right.’ ”

We all know that high-fashion garments are specifically designed to be worn by women with almost laughably boney frames. And most of us agree that women with skeletal bods are not all that attractive, for the most part. Most guys like a little heft, a little womanliness to hold onto.

But I’d like to stand with Nimoy inside a Walmart in Emporia, Kansas, or stroll with him through a midwestern airport, and I’d like him to point to all those Jabba-sized women who would collapse from exhaustion if they had to walk a mile through the woods and explain to me how they look “right.” Morbid obesity has never been and never will be an exuder of natural God-like radiance. It’s an affliction and a life- shortener and a metaphor for decline-of-the-American-empire sloth. Let’s hear it for family-size buckets of Kentucky Fried Chicken around the dinner table and bowls of Ben and Jerry’s cookie-dough ice cream on the coffee table while watching Desperate Housewives (which I, in my New York dementia, actually watched last night).

Nimoy is an elegant chubby chaser using his upscale Dr. Spock/Man Ray credentials to achieve certain goals.

Time to leave

The Cannes trip (JFK to Munich, Munich to Nice) begins at 8 pm eastern this evening. It will conclude around 12:15 pm Tuesday in Nice, which is 6:15 ayem in Manhattan and 3:15 ayem (close to the hour of the wolf, when the demons and the nightmares come out) in Los Angeles. I probably won’t post anything until three or four hours after that.

It’s ironic and almost sad to think of all those thousands of insomniac Los Angelenos tossing and turning at that hour, thinking about how scary and theatening everything is and listening to that far-away, deep-down howl in their souls, while their counterparts in Nice will be trudging along an airport tramway and rubbing the sleep out of their eyes and soon to be outdoors and curbside and staring up at the bright blue sky and breathing in that almost fragrant, vaguely salty Mediterranean air.

Year’s Best & Worst So Far

Over a third of ’07 (19 weeks out of 52 weeks) is behind us, and with the summer season just launching and Cannes due to start in three days, here’s the HE rundown for 2007 superlatives so far. 12 first- raters (including 4 festival flicks yet to be released), 19 above-average or not-half-badders, 24 that were either barely tolerable or outright awful, and 6 unseen. A total of 55 films that made some kind of strong impression. Feel free to add, subtract, debate, etc.

BEST SO FAR (9): A tie between Zodiac and The Lives of Others (an ’06 release as far as end-of-the-year awards considerations were concerned, but which opened in February) for best of the year. Runners-up: The Host, Reign Over Me, The Wind That Shakes the Barley, Black Book, Stephanie Daley (except for the weak ending), Quentin Tarantino‘s “Death Proof” half of Grindhouse, 28 Weeks Later.

BEST NOT-YET-RELEASED FESTIVAL FILMS OF THE YEAR (4): Once (dir: Jon Carney, Fox Searchlight, opening 5.18), La Vie en Rose (dir: Olivier Dahan, Picturehouse, opening 6.8), Grace is Gone (dir: James C. Strouse, Weinstein Co.); Resurrecting the Champ (dir: Rod Lurie, Yari Film Group)

BEST PERFORMANCES SO FAR (randomly listed): Marion Cotillard in La Vie en Rose, Chris Cooper in Breach, Adam Sandler in Reign Over Me, Amber Tamblyn in Stephanie Daley, John Cusack in Grace is Gone, Mark Ruffalo, Robert Downey, Jr., Jake Gyllenhaal, Anthony Edwards in Zodiac, Julie Christie in Away From Her Samuel L Jackson in Black Snake Moan and Resurrecting the Champ, Glen Hansard and Marketa Irglova in Once, Anthony Hopkins in Fracture, Laura Linney, Gabriel Byrne in Jindabyne, Hilary Swank in Freedom Writers, Justin Timberlake in Alpha Dog.

MOST IRRITATING PERFORMANCE BY A TALENTED ACTOR: Joseph Gordon Levitt in The Lookout.

BEST DOCS (3): God Grew Tired Of Us, An Unreasonable Man, Maxed Out, The Prisoner, or How I Planned to Kill Tony Blair.

DISTINCTLY ABOVE AVERAGE (9): Breach, Black Snake Moan, After the Wedding, Red Road, Jindabyne, Fracture, Paris Je’taime, Away From Her, Lucky You.

SO-SO, NOT HALF BAD (10): Breaking and Entering, Freedom Writers, Alpha Dog, Days of Glory, Factory Girl (George Hickenlooper‘s film would rate “above average” if the raw, funkier early version had been released instead of the tidied-up, re-shot Harvey version), I Think I Love My Wife, The Lookout, The Hoax, Disturbia, Paris Je’taime.

TOLERABLE (9): Shooter, The Hawk is Dying. The TV Set, Everything’s Gone Green, Lonely Hearts, Zoo, In The Land of Women, Waitress, Music and Lyrics, Day Night Day Night.

RANK, COY, UNGENUINE, OFF-BALANCE, INEPT, TEDIOUS, HALF-ASSED (14): The Astronaut Farmer, Starter for 10, Wild Hogs, Norbit, Because I Said So, Ghost Rider, the “Planet Terror” half of Grindhouse, Hannnibal Rising, The Number 23, 300, The Last Mimzy, The Reaping, Are We Done Yet?, Diggers.

SPECIAL STAND-ALONE, SUPER-COSTLY, TURGIDLY WRITTEN, OVER-CG’ED, SUPER-STINKO CATEGORY (1): Spider-Man 3.

DIDN’T SEE ‘EM (6): Blades of Glory, Adam’s Apples, Triad Election. Brand Upon The Brain, Civic Duty, Georgia Rules.

“A Mighty Heart” trailer

Only a few days before its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, and therefore time to consider the trailer for Michael Winterbottom‘s A Mighty Heart (Paramount Vantage, 6.22).

I’m intrigued by Angelina Jolie‘s skin pigmentation and black tendril-like curls, and I presume she gives a decent performance as the widowed Mariane Pearl, but right away you can tell that Dan Futterman (i.e., the ’90s indie actor whose Capote screenplay was nominated for a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar last year) gives the more interesting performance as the kidnapped-and-murdered Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl.

Here’s hoping that Winterbottom and his Mighty Heart screenwriters, John Orloff and Laurence Coriat, gave Futterman a bit more dialogue and screen time than Costa-Gavras gave John Shea in Missing.

Goldstein and the kids

L.A. Times columnist Patrick Goldstein rounded up a few 13 and 14-year-olds and showed them some summer trailers. Here’s what they had to say about the totally bash-worthy Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (Disney, 5.25):

Kid #1 (i.e., Ryan) said, “I know I’m going to have to see it, but I don’t think I’m going to like it. It really looks repetitive. But I guess I have to go.” Kid #2 (i.e., Adam) said, “It just looks horrible, so over the top, with one fight scene after another. I give it one point, mostly because Chow Yun-Fat is in it.” And Kid #3 (i.e., a girl named Simona), said, “We’re just tired of the whole series. It feels unnecessary. They just want our money.”

These kids are obviously very perceptive and iconoclastic. I also admire where they’re at spiritually. They’re hip to the horseshit and clearly sick of the same old posturing Gore Verbinski-Jerry Bruckheimer-Johnny Depp crap, and they don’t want to just march into the multiplexes like brainless monkeys and lay their money down without a reasonable prospect of seeing something they might actually like. They want something better, and who can blame them? But do they represent mainstream teens, or are they elitists of some kind? (They’d have to be a little bit picky or peculiar to know Goldstein in the first place…no?)

Forget “Triangle”

Triangle, a Chinese crime pic co-directed by Tsui Hark, Ringo Lam and Johnnie To, has been added to the Cannes Film Festival’s out-of-competition slate. This is somewhat exciting as far as the idea of three directors directing a film with a single narrative line is concerned. But if they want Hong Kong action aficianados like me to see it, they’re going to have to show it sometime in the daylight or early evening hours. The only screening is set for Friday morning at 12:20 ayem, which of course means it’ll actually start around 12:35 or or 12:40 (late-hour screenings never, ever start on time) and end around 2:15 or 2:30 ayem, which means the earliest I’d hit the hay would be an hour later, which means I’d almost certainly miss the next morning’s 8:30 ayem screening. No way, not me.

Coppla’s “Youth” going to Rome

Varietyr‘s Nick Vivarellis reported Thursday that Francis Coppola‘s Youth Without Youth, a World War II-era saga about an old professor (Tim Roth) imbued with a kind of immortality, will have its world premiere at the RomaCinemaFest, which runs Oct. 18th through 27th. Wait…no Venice or Toronto or Telluride film festival unveilings in September? I guess that’s what “world premiere” at an October film festival would mean, right? Obviously somebody doesn’t want the Toronto or Venice or Telluride-attending journos to have the first looksee. Now, let’s see…what does that suggest?

Dargis on Marvin

“Lee Marvin moved across the screen like a shark coming in for the kill,” Manohla Dargis has written in a 5.11 N.Y. Times appreciation for this late, great actor whose films are being honored with a retrospective series at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade theatre.

“Long and lean, with shoulders that looked as wide as his hips and hair as silver as a bullet, he seemed built for speed. He roamed across genres, excelling at gangsters and cowboys. Romance was not his thing. He could make you laugh, at times uneasily, but it’s his bad men that stick in your head. They are scary as hell, sometimes seductively so, because their every punch and twist of the knife seems delivered not in the heat of violence but in its chill.”

Not me. I’ve always admired Marvin’s brute masculine force, bit I’ve always preferred his good-guy variations — Walker in Point Blank (that’s right — Walker is a man of steely character and admirable fortitude in that film), the dry-mannered mercenary in The Professionals, the drunken gunfighter and his evil twin brother in Cat Ballou, the flinty Army officer in The Dirty Dozen, the washed-up athlete in Ship of Fools, the good hired-gun in Prime Cut, etc.

Marvin’s bad guys, by contrast, always seemed way too easy for a guy with that voice, those eyes, that size. His baddie-waddies in The Wild One, The Big Heat and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance always brought out that Bob Dylan in me — i.e., “All right, I’ve had enough…what else can you show me?”