HE is shocked and very sorry to read about the death of poor Jessica Campbell, known for Freaks and Geeks and her stand-out supporting role in Alexander Payne‘s Election. She was only 38. I loved her “Tammy Metzler” in Election…she just about stole the film. Condolences to Payne, Cameron Crowe and everyone who ever worked with her. Apparently she passed on 12.29 but her death wasn’t announced until today or yesterday. Not a Covid thing but otherwise unexplained and mystifying.

Jeffrey Wells

Jeffrey Wells

White-Haired Toady

From “Pence Reached His Limit With Trump — It Wasn’t Pretty”, a 1.12 N.Y. Times report by Peter Baker, Maggie Haberman and Annie Karni:

Willis Atones For Rite-Aid Incident

Our brief national convulsion over Bruce Willis‘ mask-averse behavior at a West Hollywood Rite-Aid two days ago has mercifully come to an end. It is now time to move on and focus our attention on the House of Representatives’ impeachment vote.

Tuesday, 1.12, “Rite–Aid Mask Rebel“: [On Monday, 1.11] Bruce Willis showed those Rite-Aid bitches who the daddy is and how to stand your ground when it comes to mask refusal.

Willis actually roamed his ground while declining to pull his bandana up around his nose, and then he thought better of it and left the Rite-Aid like a man, striding out proud and tall.

I’m presuming that the altercation happened at the Rite-Aid at the SW corner of Fairfax and Sunset. I’ve been there many times so don’t tell me. When the employees tell a customer to mask up, they mean what they say and say what they mean.

But Willis apparently wasn’t in the mood to hear it, and so…well, nobody knows if he replied with actual words but his actions clearly said “you don’t tell me to mask up…you tell others maybe, but not me.”

David Mamet’s “Things Change”

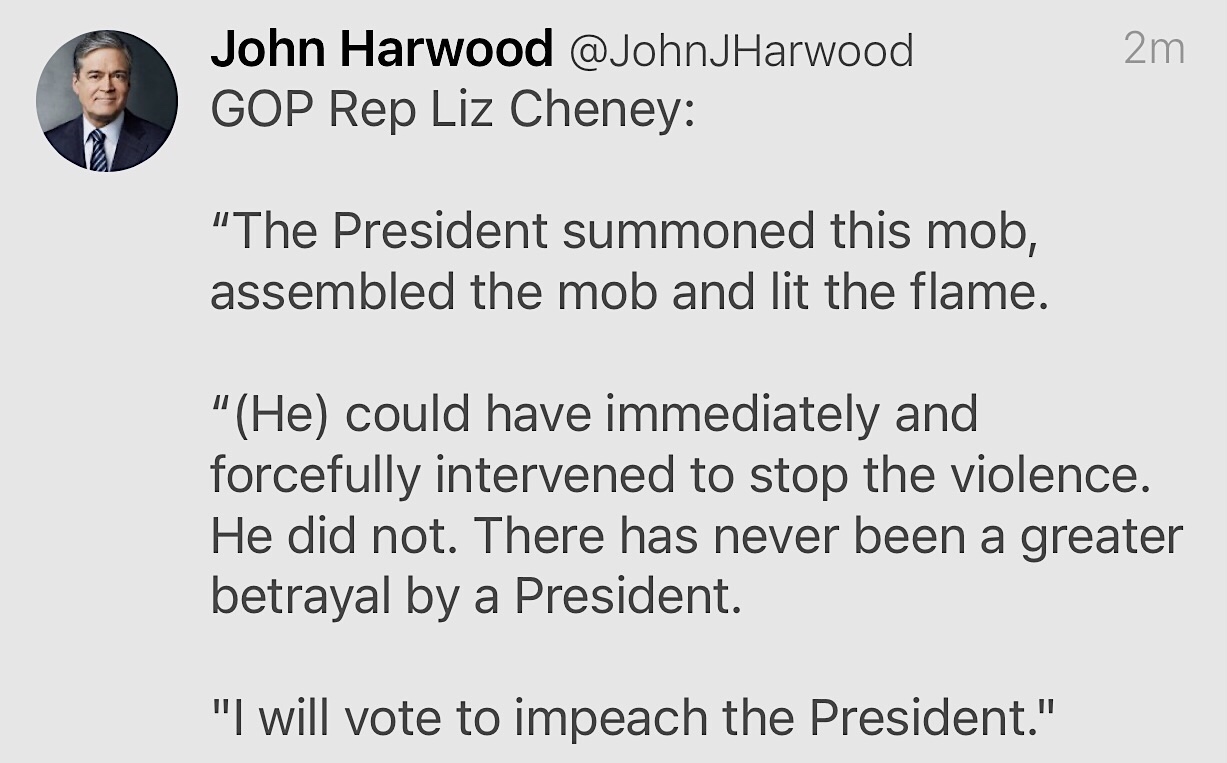

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, easily the most evil and cold-blooded Republican in the Senate, and Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the most rabid and conniving Republican dog in the House, are both talking about throwing Donald Trump under the bus, according to N.Y. Times reporter Maggie Haberman.

Excerpt: “Senator Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader, has told associates that he believes President Trump committed impeachable offenses and that he is pleased that Democrats are moving to impeach him, believing that it will make it easier to purge him from the party, according to people familiar with his thinking. The House is voting on Wednesday to formally charge Mr. Trump with inciting violence against the country.

“At the same time, Representative Kevin McCarthy of California, the minority leader and one of Mr. Trump’s most steadfast allies in Congress, has asked other Republicans whether he should call on Mr. Trump to resign in the aftermath of the riot at the Capitol last week, according to three Republican officials briefed on the conversations.

“While Mr. McCarthy has said he is personally opposed to impeachment, he and other party leaders have decided not to formally lobby Republicans to vote ‘no,’ and an aide to Mr. McCarthy said he was open to a measure censuring Mr. Trump for his conduct. In private, Mr. McCarthy reached out to a leading House Democrat to see if the chamber would be willing to pursue a censure vote, though Speaker Nancy Pelosi has ruled it out.

“Taken together, the stances of Congress’s two top Republicans — neither of whom has said publicly that Mr. Trump should resign or be impeached — reflected the politically fraught and fast-moving nature of the crisis that the party faces in the wake of last week’s assault by a pro-Trump mob during a session to formalize President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s electoral victory.”

None Too Soon

HBO should have cleared the decks in order to get Real Time with Bill Maher on the air last Friday, a week ahead of schedule. Two days after the Capitol insurrection, there was a dire need for the usual let-it-all-hang-out…the frank acknowledgments and deep-dive inquiries that Maher always tries to provide. In any event this Friday’s debut episode (1.15) should be…well, who knows. But given what’s happening right now, it’s not crazy to expect a “humdinger” of some kind.

A Nightmare on Obesity Street

The texting went as follows early this morning, World of Reel‘s Jordan Ruimy and myself…

JR: Did you read about the new Aronofsky? It’s about a 500-pound gay couch potato who’s been eating himself to death. Based on Samuel D. Hunter’s 2012 play. With Brendan Fraser as the fat guy.

HE: Oh my God…metaphor! The dead obese guy in Se7en comes back to life and merges with Mr. Creosote. And we get to watch it!

JR: Hah, Creosote is exactly who popped in my head the minute I heard about this. The Whale!

HE: Fraser isn’t heavy enough to play it without a fat suit.

JR: Very small budget

HE: Quality-brand fat suits can be costly

JR: Christian Bale could have put on 400 pounds easy.

HE: Fraser lost his A-list status because he put on too much weight and lost too much hair. I know it’s a cliche for me of all people to have this reaction, but I really, REALLY don’t want to see this.

JR: It’s described as a story of “redemption”. Similar thematically to The Wrestler.

HE: A Reddit guy says “the long-awaited Brenaissance has arrived!” Another says “hey, Brendan is getting work again!” Third guy: “He’s recently worked with Danny Boyle on FX TV show Trust and is the voice of a main character in the popular DC comic book TV show Doom Patrol. The Brenaissance already began, this is just the continuation.”

Consider Charles Isherwood‘s N.Y. Times review (11.5.12) of the play.

Best Sidney Lumet Urban ’70s Film Since…

I was initially suspicious about Shaka King‘s Judas and the Black Messiah (Warner Bros., 2.12), a period drama about late ’60s Black Panther activist and firebrand Fred Hampton, who was murdered by the FBI in December ’69.

One thing I didn’t care for was the on-the-nose title. The Chicago-based Hampton, 21 at the time of his death, cared a great deal about revolutionary social change, but there was nothing messianic about the guy — he was just a dedicated, no-bullshit leader of the Illinois branch.

Secondly I didn’t trust the early award-season enthusiasm shared by Variety‘s Clayton Davis, especially given his Awards Circuit ties to Keith Lucas, who co-authored early drafts of the Messiah script (and who shares a story credit with his brother Kenny)

Then I saw Judas and the Black Messiah a couple of weeks ago, and right away I found myself trusting — believing in — the ’70s milieu and the unforced, matter-of-fact, Sidney Lumet-ish mood of the thing. King isn’t trying to make a 2020 BLM version of what happened in Chicago 51 years ago, but attempting to show the way things actually were. He’s really dug into the history and the climate.

And so the serving is tangy and authentic — convincing late ‘60s milieu, first-rate lensing by Sean Bobbitt, unforced editing by Kristan Sprague, ace-level production design and art direction by Sam Lisenco and Jeremy Woolsey (respectively), and drillbit performances top to bottom. Bobbitt, of course, has been Steve McQueen‘s dp for several years (Hunger, Shame, 12 years A Slave, Widows).

I was especially struck by the fact that Judas and the Black Messiah is only partly an attempted deification of Daniel Kaluuya‘s Hampton, although a valiant effort is made to sell Hampton as a charismatic, sexy-eyed hardcore. The surprise is that LaKeith Stanfield‘s portrayal of the real-life William O’Neal, a guilty, haunted FBI snitch who ratted Hampton out and wound up committing suicide at age 51, is a far more fascinating figure.

Kaluuya is fine as far as Hampton is written, but Stanfield owns this film. The twitchy O’Neal is oddly more affecting because he’s a jittery, two-faced rat in a cage, and on some strange level your heart goes out to the poor fucker. He’s Gypo Nolan in The Informer but without the boozy bellowing.

All through the film you’re muttering “stand up, save yourself, don’t do this, stand with your own,” and there’s something about O’Neal’s failure to do this combined with that look of trepidation in his eyes….it’s not that he’s “sympathetic” (far from it) but his dodgy personality and the pressures upon him constitute a more interesting character.

So I’m sorry but the smartest SAG + Oscar play isn’t a Best Actor push for Kaluuya (although there’s no harm in trying) but a Best Actor or Best Supporting Actor nomination for Stanfield. If Victor MacLaglen could win Best Actor for The Informer, Stanfield should be an easy pocket drop, especially considering that his performance is far more complex than McLaglen’s.

Best Director and Best Cinematography noms are also warranted. Kudos also to the supporting cast — Jesse Plemons as O’Neal’s FBI handler plus Dominique Fishback, Ashton Sanders, Martin Sheen (as J. Edgar Hoover), Algee Smith, Lil Rel Howery, Jermaine Fowler.

A friend says he “isn’t as high on it” as I am. “There have been so many movies like it before (Donnie Brasco, American Gangster) and the betrayal aspect also reminded me of White Heat, but the performances are excellent (especially Stanfield) and Bobbit’s photography should get nominated.”

“I’m Fine…BLM Was Worse Last Summer”

Obstinate to the last, his own wavelength, radio signals from the dwarf planet Pluto, etc.

Fine With Me

One less Trump-supporting billionaire…an odious, over-fed figure…a symbol of ruthless self-interest… unenlightened shadows cast…down through all eternity, the crying of humanity.

Unmistakably Awful

First, if I’ve explained this once I’ve explained it 25 times — lead protagonists are not allowed to suddenly wake up from a nightmare by sitting up wide-eyed and gasping. Jimmy Stewart‘s Scotty Ferguson did this 62 years ago in Vertigo, but it’s not permitted any more because it’s been DONE TO DEATH.

Second, Clarice Starling isn’t a celebrity — she’s just an FBI grunt who happened to play a key role in catching the infamous Buffalo Bill. News reports may have mentioned her role in the capture but she didn’t hire a publicist to hype her exploits because junior FBI agents don’t do that.

Third, it is therefore IDIOTIC for an older woman of authority to say to Starling, “You are a woman with a very public reputation…for hunting monsters.” No, she isn’t because she didn’t star in an Oscar-winning movie — she’s just a junior FBI agent who graduated from the FBI Academy a year or so ago. Nobody knows who she is — FBI agents don’t want publicity — they’re modest investigators and law enforcers.

The stupidity is staggering.

The Buckingham’s “Don’t You Care?”

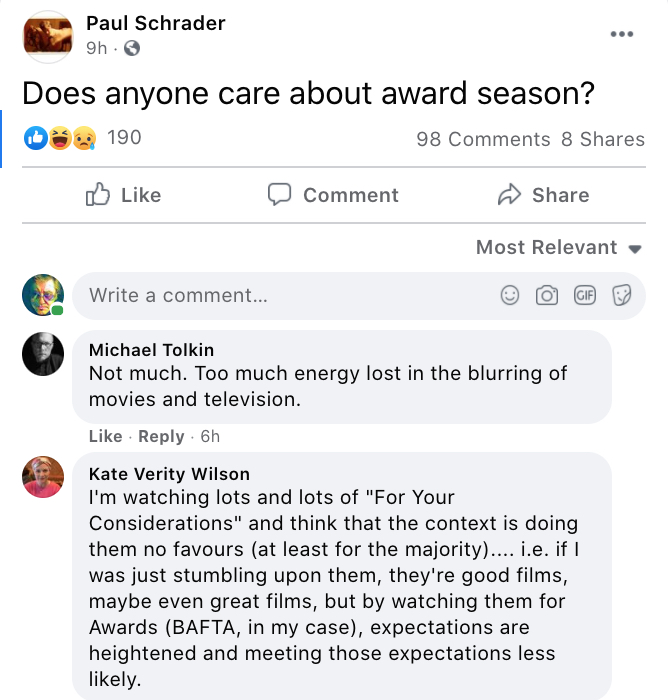

Easy Answer for Paul Schrader: It’s hard to gauge how much the Academy membership cares right now about the streaming pandemic Oscars, especially with the big telecast over three months away. What’s certain is that everyone is too afraid to vote with their gut about anything. There’s only one way to vote and that’s defensively. Here’s how Sasha Stone and HE have explained it in previous posts:

Stone explanation #1: “Bloggers scan each project for un-wokeness. Films by and about white males are mostly fair game for any kind of attack, and hopefully will eventually be just completely shunned. One tweet is all it takes to send a wave of hysteria through the hive mind and suddenly that film, too, is problematic. And anyone who likes the film or votes for the film is likewise caught up in that shitstorm.”

HE Explanation: “Twitter is the judge and jury but no one wants to be seen as complicit in anything outside the approved wokester safety zone, and so they vote accordingly.”

Stone explanation #2: “Bloggers and critics are therefore modulating for this potential blowback with [careful] choices. We’re all predicting the Oscar using the same method. In an ordinary year we might pick a movie [that] Oscar voters would likely go for, given what we know of the Academy’s taste. This year, we compensate for the ‘woke scare’ and we say ‘this is the movie they might go for if they are wanting to send a message that they are not racists or sexists or transphobes.’ In short, people will likely be voting from a place of defending themselves from potential attacks.”