In yesterday’s thread about Ava Duvernay‘s When They See Us, “Mr. F” said something that I regarded as borderline astonishing. “Now matter how often I see it,” he said, “I remain amazed at Wells’ ability to criticize a character or person for acting differently than he would.”

Mr. F was apparently serious. He was saying that the correct way to watch a drama is to immerse yourself in the basics (story, character, milieu, tone) but without drawing upon your own life experience for perspective or judgment.

Maintain a strict distance, Mr. F was saying. By all means submit to whatever the characters are going through, all the while considering their various motives, dreams, delusions and appetites. But do so impersonally. You’ll only muck things up if you merge the story with your own saga or knowledge of how life works. Turn off your mind, forget what you know, dumb yourself down.

Let me explain something very clearly: I’ve always put myself into the narrative and especially the shoes of various characters, and I always ask myself “is this how I’d play my cards?” Or “is this how I’d react?” If not, I say “what then are their motives for acting in a way that I don’t agree with? Why would they behave in a way that seems a little outside my realm or which doesn’t seem to make basic sense?”

I’ve been watching films, plays and TV dramas this way for decades…hell, since I was seven or eight years old. I have an idea that tens of millions of others do the same.

Going back to the eras of Aeschylus, Agathon and Sophocles the basic task of drama has always been to merge the proverbial audience member with the experience, mindset and emotional leanings of the lead character[s]. The idea has always been to “walk a mile in these characters’ shoes, and once you’ve gotten to know them decide for yourself if he/she is living her life sensibly or radically or dangerously or brilliantly or something in between.”

If you don’t use your own life experience to assess the wisdom or bravery of a given character, to determine whether he/she is acting foolishly or clumsily or with enviable political skills…if you’re not bringing what you know into a narrative and making assessments of various characters based on what you’d do or wouldn’t do if you were in their shoes…if you’re not engaging with a drama as a human being with memories, emotions and regrets of your own then what the hell are you doing?

Mr. F. feels that the best way to watch a film is to adopt the mentality of a cupcake or a toaster or a chunk of mozzarella cheese.

Mr. F quote: “It’s a mistake if you’re evaluating character choices based on what you would do, assuming it’s clear from the narrative why they’re doing what they’re doing…it’s just empathy.”

HE to Mr. F: You can’t have empathy without feelings of allegiance or identification or at least understanding. You have to be persuaded to emotionally join this or that character’s team, even if they may not the nicest people you’re ever met. Failing that you have to be persuaded that a character’s reasons for doing what he/she does at least makes sense to them. That’s almost always what you get when the screenplay is first-rate.

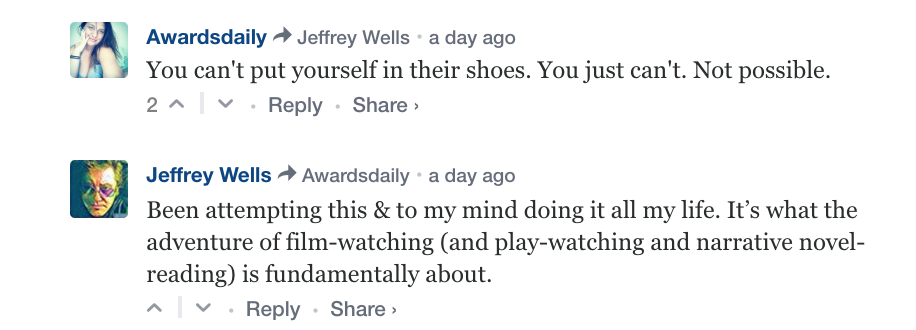

Sasha Stone quote: “You can’t put yourself in their shoes. You just can’t. Not possible.”

She meant the unjustly prosecuted and jailed Central Park Five. My suburban whitebread experience, Sasha was saying, makes me incapable of understanding anything about these guys — what they were about or what was driving them onward or whatever. They might as well be microbes from the Planet Jupiter, Sasha basically meant.

Well, bullshit to that. The screenplay and the acting in When They See Us happen to be good enough to allow me to relate, to discover parallels between what these poor guys went through and my own experiences and understandings. This is what makes a film good. Either you build bridges between the audience and the characters or you don’t.