Factory Final

I didn’t say very much about Factory Girl when I riffed on it last August (I’d seen an early, far-from-finished cut) — I mostly confined myself to praising Sienna Miller‘s performance as Edie Sedgwick, which I thought (and still think) is a deeply sad, near-perfect communing with the spirit of a proverbial damaged debutante.

Last night I saw a more-or-less complete version of Factory Girl (i.e., almost but not quite the exact same cut that’s opening today in Los Angeles), and guess what? This is a much better film — far more precise and filled in and rounded out — but I liked it a bit more when it was funkier, rawer and less “complete.” Strange but strangely true.

I realize, of course, that the choppier, more instinctual, not-quite-as-layered version that I liked or believed in a tiny bit more wouldn’t play as well with general audien- ces, and I also recognize that the current version is a more finely woven thing. I’m just saying that the old Factory Girl felt less self-conscious — it seemed hipper and more fuck-all Warholian. But no one else saw the August version so none of this matters.

Factory Girl is somewhere between a solid 7.5 and an 8 — it has sufficient dramatic potency, it’s atmospherically convincing and tonally accurate (for the most part), and it’s extremely well acted by the leads. And the rotely cautionary theme that speaks to every nocturnal scenester out there only adds to the brew. Beware of temporary coolness and clubbing around and endlessly shooting the shit with your homies over drinks — it’ll turn you into toast. Stay home more, get into your art, take walks with your dog…invest in yourself and don’t give it away.

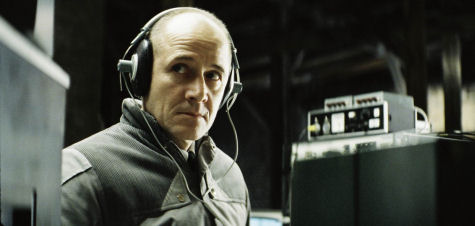

There are two significant differences between last night’s Factory Girl and the version I saw five months ago. Miller is still uncannily on-target — she still has Sedgwick’s “fluttery debutante laugh, that mixture of Warholian cool and little-girl terror, the giddy euphoria, the cracked voice,” as I wrote last summer — but Guy Pearce‘s Andy Warhol performance has been beefed up to an extent that he’s no longer a distinct supporting character but a costar. And Hayden Christensen‘s Bob Dylan character (called “Danny Quinn” in the press notes but never called anything by anyone in the film) also seems a bit more assertive and sharply defined.

The old Factory Girl was basically a Sienna show with two strong supporting males. Now it’s become a three-character piece that’s using the myth-cliche of a romantic triangle (partly if not largely based on bullshit but so what?) to provide the dramatic tension.

The story is about gay, ultra-cool Andy — ex-advertising guy who’s made himself into a Manhattan artist legend — fascinated by Edie’s jaded spirit and making her famous for being famous and yet offering nothing solid except a momentary flash of hip notoriety. Taking, studying, gliding along, going with it…and never “there” as any kind of friend, supporter or colleague whatsoever.

Along comes heavycat “Danny” geninely liking Edie for who/what she was — seeing value in her essence — while tagging Andy as a kind of user-taker vampire poseur and trying to rescue Edie from her inevitable fate, which is to be cast aside for the next whatever. And yet realizing in the end that she’s too damaged and off-balance to really stand on her own.

And then Warhol, who’s come to resent Edie for pursuing a “Danny” relationship, throws her over for Nico (of the Velvet Underground), and Edie subsequently gets caught up in drugs and debauch, and ends up dead — the old drug habits — five years later.

Pearce’s Warhol may be grossly simplified compared to the real McCoy, but he’s trippy and absorbing in a darkly downtown sort of way. Half-comic and half demonic, he’s one of the most obliquely cool screen villains I’ve ever spent time with — no exaggeration. His malice and selfishness is cloaked in a kind of hip vacancy (i.e., the standard “oh, wow” Warhol of legend, which wasn’t who the guy really was), but there’s obviously something cold and almost monsterish about him — a guy so damaged and ruthless that he’s forgotten where he put whatever vestiges of common humanity he may have once had.

I believed Factory Girl‘s atmospheric details; it seemed right to me in all kinds of ways. But I had minor problem with costar Jimmy Fallon‘s hair, which goes from dark brown to light brown-orange in a single early cut. Abrupt hair shifts are never good for anyone in any realm! Harvey Weinstein should spend an extra $30,000 to give Fallon a CGI hair fix.

Edie Sedgwick may not have even slept with Bob Dylan, much less had a raging love affair with him….but “Danny’s” entry into the film does two things: it provides a semi-decent dramatic structure-conflict, and it allows Christensen to deliver the first better-than-decent performance of his life.

I’ve disliked each and every Christensen performance I’ve seen prior to Factory Girl (he’s the reason I can’t bear to watch any portion of the last two Star Wars prequels) but he somehow finds a way into the Dylan attitude and voice, and seems more or less relaxed and centered in it. He has a near-great scene when he’s posing for Warhol’s 16mm camera inside the Factory while looking around and asking if “this is where you paint your cans of beans,” and at the same time clearly implying that Warhol is a selfish prick. For the first time in his brief career, Christensen doesn’t seem to be straining for emotional intensity.

The end credits use some talking-head comments from the late George Plympton and (I think) one of Sedgwick’s brothers to moderately interesting effect, although it feels a wee bit tacked-on and superfluous.

Captain Mauzner’s screenplay feels right when it comes to the attitude dialogue, and the supporting performances from Beth Grant (as Warhol’s Polish mom), Armin Amiri, Mena Suvari and Illeana Douglas (as Diana Vreeland) are agreeable and bump-free. The only one that doesn’t feel quite right is Edward Herrman‘s as a Sedgwick family lawyer — his scenes seem sketchily written and too tidy.