Worth repeating: John Krasinski‘s A Quiet Place, Robert Eggers‘ The Witch, Jennifer Kent‘s The Babadook, Andy Muschietti‘s Mama and now Ari Aster‘s Hereditary.

Aster’s low-budgeter, which starts out in a sensible, unforced fashion before flipping the crazy switch around the halfway mark and going totally bonkers (and I mean that in the best way imaginable), is quite the brilliant horror-thriller. You can tell right away it’s operating on a far less conventional, far more original level of craft and exposition than a typical horror flick, or even an above-average one.

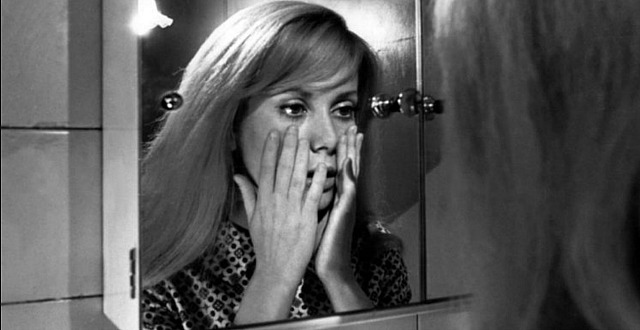

The best portions recall the classic chops of early Roman Polanski (particularly Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby) as well as Jack Clayton‘s The Innocents, but I was just as impressed by the performances — three, to be precise — as the shock-and-creep moments, and that’s saying something for a ghost film.

Hereditary

Hereditary director-writer Ari Aster during last night’s post-screening party at Neuehouse.

Hereditary

Hereditary costar Alex Wolff, director Eli Roth.

Hereditary begins as a suburban-milieu film about a family of five that’s just become a unit of four. Odd flickerings of weirdness begin to manifest, but nothing you can point your figure at. And then the number drops to three, and then the spooky-weird stuff kicks in a bit more. And then it goes over the fucking cliff.

The film is carried aloft and fused together by Toni Collette‘s grief-struck mom, Annie. It may be Collette’s most out-there performance ever. It’s certainly her most boundary-shattering in terms of connecting with the absolute blackest of currents. Collette convinces you that her character isn’t suffering a psychotic breakdown of sorts, that she’s going through her torments because it’s all 100% real, and at the same time allows you to consider that she has gone around the bend. Or that we may be watching a metaphor for the tortures of grief-driven insanity.

As the narrative advances Annie becomes more and more nutso, but relatably so. That’s quite the acting trick.

Nearly as effective is Alex Wolff as Peter, Collette’s guilt-crippled teenage son, and Ann Dowd as Joan, a kindly and sympathetic woman who meets Collette at a grief-therapy group. Gabriel Byrne is a little morose as Steve, Annie’s husband. The curiously featured Milly Shapiro is fine as Charlie — Peter’s younger sister, Annie and Steve’s daughter.

Read more