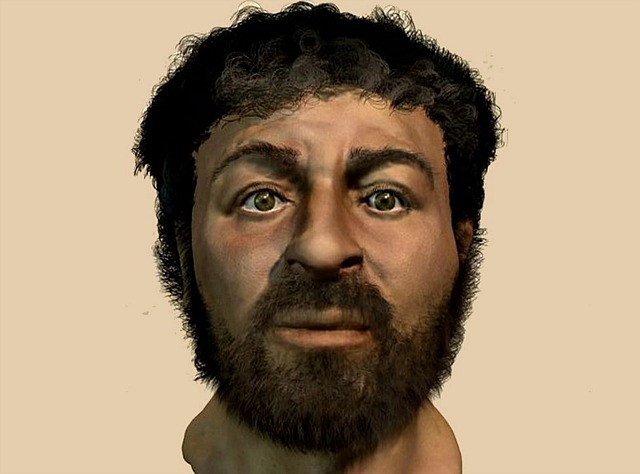

Earlier today Paul Schrader posted the below photo on Facebook, and with a question: “Who is this?” Answer: An approximate representation of the features of Jesus of Nazareth, based on knowledge of facial bone structures of ancient Judeans and passed along by “British scientists, assisted by Israeli archeologists.” The portrait was revealed in a January 2015 issue of Popular Mechanics.

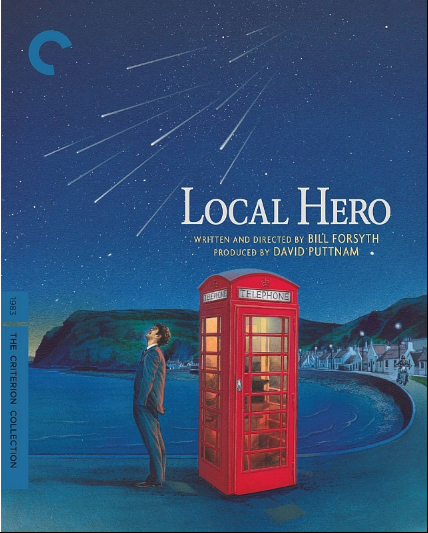

HE reply to Schrader: You know who he looks like? Seriously? Akim Tamiroff in Sam Wood’s For Whom The Bell Tolls.

Where did he get his hair done? Definitely a choppy brush cut due to a lack of good sharp scissors. As if his hair had been trimmed with a sheep herder’s knife of some kind. I’m guessing that most poor guys got a once-a-year haircut back then. Maybe there was a shepherd with a knack for giving such haircuts, which constituted a side business. A guy known to Yeshua and the disciples, I’m thinking. Maybe they all went to him at the same time and got a group rate.

A day or two ago I saw a guy in the Beverly Center Apple store who looked a lot like this, I swear to God. Faded red hoodie sweatshirt, madras shorts, sandals. He was checking out iPads. The Second Coming?

A sizable segment of right-wingers (i.e., the Mike Pence, Megyn Kelly crowd) still believe that Yeshua of Nazareth looked like a handsome, blue-eyed Anglo Saxon linebacker for the University of Michigan. Only with long, flowing, freshly shampooed honey brown hair.

Akim Tamiroff in For Whom The Bell Tolls.