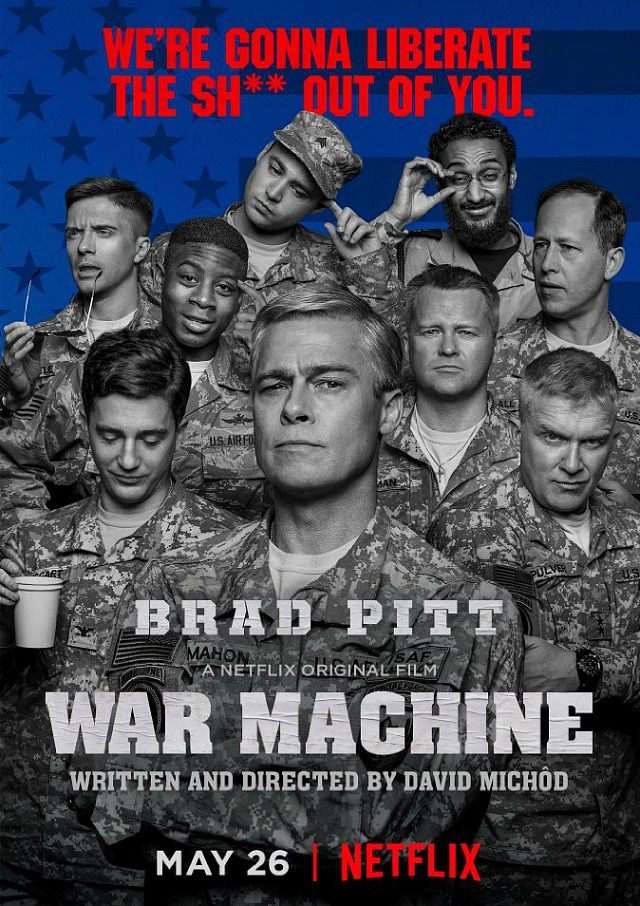

I caught David Michod and Brad Pitt‘s War Machine (Netflix, 5.26) a couple of weeks ago in Manhattan. I was expecting a problem given the effort I had to invest to attend an advance screening, but I was surprised to discover it’s not all that speed-bumpy. I found little to dislike and a lot to generally admire, and I was really taken by three or four scenes. It’s not a half-bad film.

As I noted on 5.10, Keith Stanfield gives a serious pop-through supporting performance. He’s the guy you’re talking about when it’s over.

For some Brad Pitt‘s oddly one-note, gruff-voiced performance — General Buck Turgidson transposed to Afghanistan — will feel like a stumbling block, but I accommodated myself. I understand those who say that Scott’s performance worked because Dr. Strangelove was a straight-faced absurdist farce while Pitt’s performance as General Glen McMahon (based on Gen. Stanley McChrystal, the former Afghanistan war commander) argues with the generally non-farcical, matter-of-fact tone of War Machine. Pitt was obviously trying to convey something about rigid thinking, about living in the prison of can-do military machismo.

The problem, as Washington Post critic Ann Hornaday has mentioned, is that the over-the-top mannerisms invite derision, and so whatever genuine respect or affection that McChrystal got from U.S. troops and colleagues is ignored or brushed aside.

War Machine is didactic, but it unfolds in a rational way. It’s smartly assembled. It’s not forced or turgid or hard to get. It’s a surface-y thing, yes, but it does have an element of sadness and regret in the third act. It’s a condemnation of myopic mentalities, and of American arrogance and bureaucratic cluelessness. It has a problem or two, okay, but is certainly no wipeout. Not in my eyes, at least.