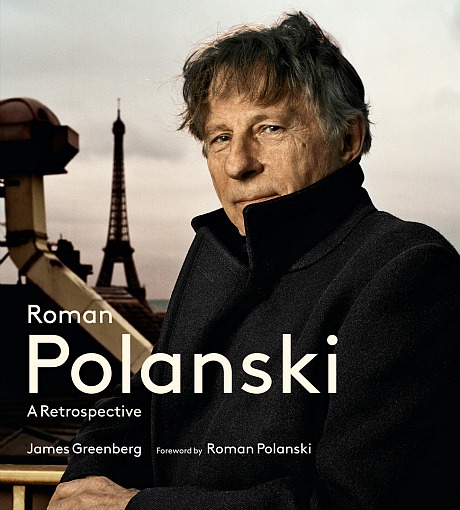

Roman Polanski-philes now have James Greenberg‘s Roman Polanski: A Retrospective to add their biographical collection. I’ve torn through about half of this 287-page book since returning from New York on Thursday night, and I can say without question that Greenberg’s essays on Polanski an∂ his films are as authoritative, perceptive and well-finessed as F.X. Feeney‘s in his 2006 Polanski book, and that the photos in this coffee-table hardback are second to none. It’s both easy to read and easy not to read, but you’ll want to read it.

Greenberg and I did a phoner this morning around 10:30 am — here’s the mp3.