HE’s Manhattan correspondent Jett Wells attended Tuesday night’s (11.1) premiere screening of Oren Moverman‘s Rampart at the Sunshine plex on Houston Street. Here’s his report:

Rampart

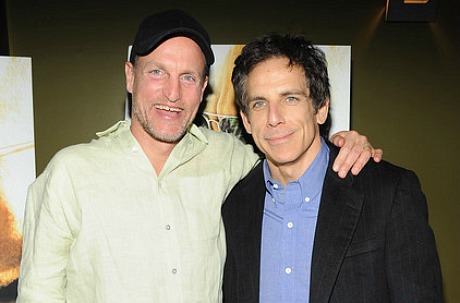

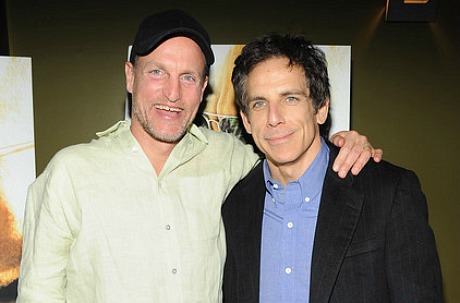

Rampart star Woody Harrelson, Ben Stiller at Tuesday night’s premiere.

“It felt suffocating being surrounded by a ridiculous and cluttered amount of celebrities in such a small theater. Is that Courtney Love? Yup. Martha Stewart? Yes, indeed. Oh hey…yes, Steve Buscemi and Michael Shannon looking for their seats. You couldn’t talk about the iconic faces without looking like an ogling jerkoff, but that didn’t stop all the turning heads in the front rows.

“Before the screening Ben Stiller delivered an introduction, explaining how he first met Oren at the Nantucket Film Festival a year or two ago. He was a big fan of his work but he hadn’t seen his new film with all-star cast featuring Woody Harrelson, Sigourney Weaver, Steve Buscemi, Ice Cube and Robin Wright. He asked the reluctant director to say a few words. “Just stick through it to the end,” Moverman said. And then we were off.

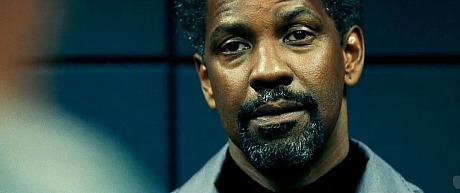

“Rampart is about an angry, Vietnam-vet, sex-addicted, misanthropic LA cop (Harrelson) who longs for the days when cops could muscle out the bad guys by taking them out and cleaning up the red tape later with winks all around. I think.

“While the film is built around strong writing and clever camera angles, the only thing I could pull out this wonky plot line is Harrelson’s performance — his darkest and most sincere since Natural Born Killers. He smokes what seems like six cartons of cigarettes throughout the film (a la Jeff Bridges in Crazy Heart), while sleeping with Robin Wright and other random women as he gets his rocks off while acting as a righteous, misunderstood hero defending his name.

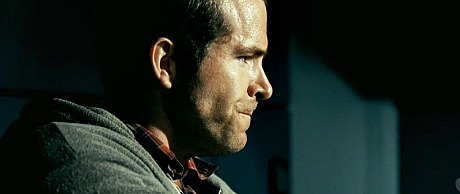

Rampart

Rampart director Oren Moverman, Woody Harrelson.

“His character, Dave ‘Date Rape’ Brown, is an evasive father with two ex-wives. He’s been on the job for 27 years. The setting tells us the LAPD is in the middle of scandal, but Moverman doesn’t focus on the details. Brown, whose nickname stems from his having allegedly killed a serial rapist without being convicted, is convinced that higher powers are trying to use him as a patsy to take the fall for the corrupt city government after he’s filmed beating a man almost to death. He’s convinced it was all set-up.

“The story seems more convoluted in retrospect, and it feels that way when you’re watching it. But the one bothersome, ignored plot line in the film is Brown’s family situation. He lives with what seems to be his two ex-wives who live in two separate adjoining condos, and he living in a small adjacent guest house. While his two daughters despise him for his secrecy and drinking problems.

“It feels like a Mormon polygamy situation, but there’s no way this grizzled cop is anything like Mitt Romney so what’s the deal? It’s bothersome and distracting that no one explains what’s going on with this vital storyline.

“Brown slips into his ex-wives homes to act like a missing husband, slipping into their beds. This involves him asking in so many words, ‘Will you sleep with me?’ Really, who says that?

“Overall the film has a solid core and shows Moverman’s obvious talent, but Harrelson’s performance carries the film even if 30 percent of it doesn’t any sense. Is it an Oscar-worthy performance? Maybe, meh, but at least it reminded me what kind of performance Harrelson still has burning inside him. It’s a refreshing revival in an otherwise bizarre and frustrating film.”

Here’s my somewhat more positive Toronto Film Festival review.