Karl Malden is alive, hopefully well and three years shy of his 100th birthday. Malden was no spring chicken when he played Mitch in the original 1947 stage production of A Streetcar Named Desire — he was 35 years old. He was about 57 or 58 when he played Omar Bradley in Patton. And he was born with the name Mladen George Sekulovich . Has any marquee-value actor ever made it to 100?

Livery of Hell

I saw this flyer stuck to a wall in a laundromat yesterday in downtown Philadelphia. The concept is flat-out brilliant. An agent needs to sign John Heimbuch, and some producer needs to option the rights. Flesh-eating ghouls staggering around Elizabethan London in valour period garb and speaking in Shakespearean verse…are you kidding? I’d pay to see this film in a New York minute.

Old Time’s Sake

Easily one of the most exquisitely phrased, brilliantly performed rants in motion picture history

Spinning

One obviously can’t watch screeners, read scripts, clean the house, arrange screenings, make calls, and write stories/items at the same time. The tension created by the inability to focus on just one of these (and letting the other three go for the time being) is exhausting. At least there’s one thing I’m dead certain of — i.e., the repulsiveness of Costco-level Latin dance music, which is now throbbing through the ceiling and vibrating paint chips off the walls.

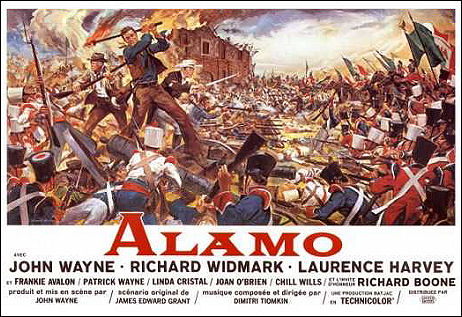

Saving The Alamo

In his most recent Digital Bits column, restoration guru Robert Harris has announced a full-on drive to raise enough cash to digitally restore two versions of John Wayne‘s The Alamo — a 172-minute general release cut, which would be rendered in either 70mm or in digital 2K or 4K, and the full-boat 192-minute roadshow version (not counting the overture, entr’acte and exit music).

A frame of the original 70mm print of The Alamo as it exists today.

How many people out there are dying to see the three hour and 12 minute version of Wayne’s 1960 epic, restored to full and glorious perfection? Well, myself for one. I’m totally queer for lustruous large-format films of the ’50s and ’60s. But this project isn’t about anticipating public clamor as much as doing the right thing by a solid, engaging, well-crafted film about true-blue patriotism, and especially one valued by old-school conservatives who believe that preserving the memory of a valorous episode in Texas history is an essential, sacred duty.

The 172-minute version will be strictly intended for theatrical screenings while the 192-minute version will be accessible only on DVD and Bluray.

I’ve been hearing about this project for years, but a commitment from MGM to render a 70mm print at the end of the year-long restoration process has been secured. Various other parties have stepped up to the financial plate in terms of pledges and whatnot. There’s no question that this beautifully shot, slightly stodgy epic needs to be digitally restored, as the original visual elements are pretty much degraded and cracked and faded all to hell. Is The Alamo a great film? No, but it’s a pretty good one, and Harris’s new venture deserves respect.

Justice

In a 3.20 interview with WWD’s Jacob Bernstein, “Depression 2.0 Queen” Suzie Orman delivers a message to George W. Bush: “You blew up every single financial vessel we had and if you think you aren’t personally responsible….well, the blame starts at the top. If I were you, I would feel so absolutely horrific that I would take every penny I had and distribute it to anybody and everybody to help them in whatever way I could. You owe the American people every penny of your fortune and your family’s fortune.”

These Three

So Knowing was #1 yesterday with $8,950,000, but the word-of-mouth may be sinking it today with I Love You, Man, which came in second with $6,350,000, poised to take the top slot. Or maybe not. I’m guessing that the three-day Knowing figure will be closer to $21 or $22 million rather than $25 million, and Man might top the $20 million mark.

And Tony Gilroy‘s Duplicity — arguably the best of the three (or certainly the best made) — will come in a distant third. The Clive Owen-Julia Roberts espionage drama earned $4,700,000 yesterday and may end up with $13 or $14 million by Sunday night. So again Roberts hasn’t opened a film, or certainly not big-time. I’d say her fee should be adjusted to $5 million per film now — no more. My two kids don’t like her, and my ex-wife dislikes her. I don’t like her either but I respect her combativeness in the same way I respect a power-hitter in baseball.

“Instant Cult Film”…what?

Seth Rogen‘s character in Observe and Report (Warner Bros., 4.10) is a hero in what universe apart from the secular universe of Warner Bros. marketing? “Eeeee!!!,” they scream as they jump up on chairs and tops of desks like girls who’ve just seen a mouse. “A cult film! A cult film! Eeeee!”

This is not a film, remember, that’s been “played for sitcom jokiness and family-friendly slapstick,” as Variety‘s Joe Leydon explained a few days ago, but which “attempts something much darker, if not downright transgressive, with a pic bound to divide auds and critics into love-it-or-leave-it camps.”

“This movie is a minor miracle, an original and unfiltered dark comedy that demolishes the mainstream-friendly comic persona that Seth Rogen’s been cultivating the last few years,” Drew McWeeny recently wrote from South by Southwest. “It’s convulsively funny, disturbingly violent, and uncomfortably carnal and intimate at times. And it’s not a redemption story about how [Rogen’s character] sorts out his problems and eventually becomes a happy or a better person. It’s a slow slide from bad to worse, and that’s exactly what makes this an instant cult classic.”

Yari Blues Again

Two days ago Amy Kaufman posted a Wrap piece about the Yari Group’s decision to go into bankruptcy last December. It’s puzzling why Kaufman decided to get into this three months later as nothing really new is reported. The standout element are two differing opinions about the state of Yari’s company before it went bust. The first is from Rod Lurie, director-writer of Nothing But The Truth as well as producer of What Doesn’t Kill You, two Yari releases that fell through a trap door when Chapter 11 was declared. The other view is non-attributable.

“The Yari team are good and smart people who got caught in the perfect storm of the economy,” Lurie says. “But it was like a drive-by shooting. Everything’s going great and then we’re on the ground, bullet-ridden.”

But later in the piece Kaufman writes that “several people who’d been working with the company said the signs of trouble had long been clear at Yari, and that Yari’s trouble were not necessarily indicative of bigger problems in the indie industry. ‘There were certainly release dates that weren’t met at Yari and bounced around,’ said one source who refused to be named. ‘In 2008, you would have been nuts to sell your film to Yari Film Group.'”

Nothing But The Truth will have a DVD and Bluray release on 4.28.09.

Respect Must Be Paid

It’s been ten months since I saw Nuri Bilge Ceylan‘s Three Monkeys at the Cannes Film Festival. To me this beautifully shot mood piece about brutal class exploitation in Turkey was a major visitation. Some felt the same way; others weren’t as enthused. It was finally acquired by New Yorker Films only to be returned to the limbo straits when NYF went bust. Then Zeitgeist stepped in. It’s now opening at Manhattan’s Cinema Village on 5.1.09 and L.A.’s Nuart on 5.27.

That’s something, at least. At the same time this doesn’t feel right. I’ve seen films at the Nuart and the Cinema Village, and the vibe is nothing special. You pay to get in, you buy the popcorn and you sit down, and every so often the floor feels sticky and greasy. And the screen isn’t that big, the sound isn’t especially strong or precise and the print is sometimes a bit worn down. (But not always. It depends.) But what a difference from seeing it in Cannes where the projection and sound levels are top-of-the-line, and you’re often carried along by a communal absorption vibe generated by the sharpest film journalists on the planet. It’s the only way to go.

“The moral undercurrent in Three Monkeys — a quietly devastating Turkish family drama about guilt, adultery and lots of Biblical thunderclaps — is in every frame,” I wrote last May. “It’s about people doing wrong things, one leading to another in a terrible chain, and trying to face or at least deal with the consequences but more often trying to lie and deny their way out of them. Good luck with that.

“I was hooked from the get-go — gripped, fascinated. I was in a fairly excited state because I knew — I absolutely knew — I was seeing the first major film of the festival. Three Monkeys is about focus and clarity in every sense of those terms, but it was mainly, for me, about stunning performances — minimalist acting that never pushes and begins and ends in the eyes who are quietly hurting every step of the way.”

Hatice Aslan, Yavuz Bingol in Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Three Monkeys.