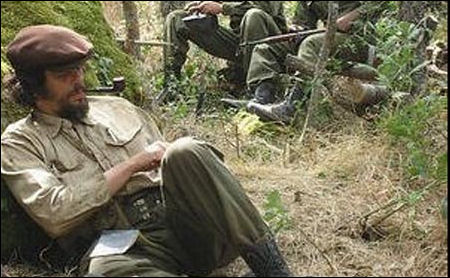

The official 2008 Cannes Film Festival announcement went up just after 3 am this morning, and the ambiguity about Steven Soderbergh‘s two-headed Che Guevara drama — The Argentine and Guerilla — has been removed. It will definitely play there (possibly with The Argentine in some kind of not-quite-finished form, but whatever) and glory friggin’ hallelujah!

Once again it feels as if the festival will have an ambitious centerpiece — a long-haul piece de resistance by one of our country’s finest filmmakers that journos can argue about and pick over and send messages home about and piss off the Miami Cubans with. All is now well with the world except for the sociopathic fiendishness of Hillary Clinton.

As reported last night by Variety‘s Todd McCarthy, Clint Eastwood‘s Changeling (is there a “The” in the title or not?) is also locked in.

As predicted earlier, Steven Spielberg‘s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull and DreamWorks Animation’s Kung Fu Panda will play there out of competition, as will Woody Allen‘s Vicky Cristina Barcelona.

Walter Salles‘ Linha de passe, an urban road movie, will play in Cannes — “mostly set in Sao Paulo’s high-rise hell, about four soccer star wannabe brothers,” says Variety’s report.

Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne willl bring The Silence of Lorna. France’s Arnaud Desplechin returns with A Christmas Tale, a family drama with Catherine Deneuve and Mathieu Amalric. Atom Egoyan will arrive with Adoration. Wim Wenders will bring The Palermo Shooting, and Turkey’s Nuri Bilge Ceylan will deliver Daydreams, a kind of detective drama.

James Toback‘s Tyson, a doc about the controversial former heavyweight champion, will play in Un Certain Regard.

Jia Zhangke‘s 24 City “may well be the only major Chinese film at Cannes,” says the Variety piece, due to “a current bottleneck in the Chinese censorship process, which includes authorizing overseas travel.”

James Toback, Mike Tyson

In Competition:

24 City, China, Jia Zhangke

Adoration, Canada, Atom Egoyan

Changeling, U.S., Clint Eastwood

Che (The Argentine, Guerrilla) Spain, Steven Soderbergh

Un Conte de noel, France, Arnaud Desplechin

Daydreams, Turkey, Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Delta,Germany-Hungary, Kornel Mundruczo

Il Divo, Paolo Sorrentino, Italy

Gomorra, Italy, Matteo Garrone

La Frontiere de l’aube, France, Philippe Garrel

Leonera, Argentina-South Korea, Pablo Trapero

Linha de Passe, Brazil, Walter Salles, Daniela Thomas

La Mujer sin cabeza, Argentina, Lucrecia Martel

My Magic, Singapore, Eric Khoo

The Palermo Shooting, Germany, Wim Wenders

Serbis, Philippines, Brillante Mendoza

The Silence of Lorna, U.K.-France, Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne

Synecdoche, New York, U.S., Charlie Kaufman

Waltz With Bashir, Israel, Ari Folman

Out of Competition:

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, U.S., Steven Spielberg

Kung Fu Panda, U.S., Mark Osborne, John Stevenson

The Good, the Bad, the Weird, South Korea, Kim Jee-woon

Vicky Cristina Barcelona, U.S.-Spain, Woody Allen

Midnight Screenings:

Maradona, Spain-France, Emir Kusturica

Surveillance, U.S., Jennifer Lynch

The Chaser, South Korea, Na Hong-jin

Special Screenings:

Ashes of Time Redux, China, Wong Kar-wai

Of Time and the City, U.K., Terence Davies

Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, U.S.-U.K., Marina Zenovich

Sangue Pazzo (Crazy Blood), Italy-France, Marco Tullio Giordana

Screening of the President of the Jury:

The Third Wave, U.S., Alison Thompson

Un Certain Regard:

A festa da menina morta, Brazil, Matheus Nachtergaele

Afterschool, U.S., Antonio Campos

De Ofrivilliga, Sweden, Ruben Ostlund

Je veux voir, France, Joana Hadjithomas, Khalil Joreige

Johnny Mad Dog, France, Jean-Stephane Sauvaire

La vie moderne (profiles paysans), France, Raymond Depardon

Los Bastardos, Mexico, Amat Escalante

Milh handha al-bahr (Salt of This Sea), Palestine, Annemarie Jacir

O’ Horten, Norway-Germany, Bent Hamer

Soi Cowboy, U.K., Thomas Clay

Tin Che, (Parking), Taiwan, Chung Mong-Hong

Tokyo!, France-Japan, Bong Joon-ho, Michel Gondry, Leos Carax

Tokyo Sonata, Japan, Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Tulpan, Germany, Sergey Dvortsevoy

Tyson, U.S., James Toback

Versailles, France, Pierre Schoeller

Wendy and Lucy, U.S., Kelly Reichardt

Cloud Nine, Germany, Andreas Dresen

Yi ban haishui, yi ban huoyan, China, Fendou Liu