Michael Davis‘s Shoot ‘Em Up (New Line, 9.7) is a brilliant, ultra-violent Buster Keaton comedy, but the late-blooming Davis is, I feel, up to a lot more than just giving action fans a good ride. What he’s serving is basically satire, and we all know how that plays with people who just want the straight dope. In fact, I won’t be surprised if I hear about some action fans being irritated by Shoot ‘Em Up when it opens early next month. In a good way, I mean. Anything that pisses off the faithful is up to something right.

Action fans respect quality merchandise — I’m an absolute worshipper of The Bourne Ultimatum — but Shoot ‘Em Up is a movie about movies that peddle second- and third-rate material, and is therefore not very respectful of the action genre as it has existed since the early ’90s and the rise of Hong Kong action directors like John Woo.

The irony, of course, is that Shoot ‘Em Up was largely inspired by Woo’s Hard Boiled, a 1992 classic that was about a lot of crazy stuff, but partly about its fast-moving hero, played by Chow-Yun Fat, protecting an infant from predators filling the air with hot lead. In the current version Clive Owen is the Fat guy (i.e., a taciturn, totally gifted action machine), Paul Giamatti is the manic heavy and Monica Belucci is the hooker/ally/sexual comfort-giver.

Davis provides a good fast ride, but Shoot ‘Em Up is only somewhat interested in making its audience feel the heat. What it’s mainly about, deep down, is Davis saying to the action crowd, “Do you understand what a bunch of lowlife dipshits you guys are? Do you understand that your taste buds are up your rectum? Do you understand what a pestilence guns are, and that they provide the cheapest and dumbest movie thrills imaginable?”

There isn’t a single drop of sincerity in Shoot ‘Em Up, and yet Davis is sincerely saying the following with each and every shot: “It is completely impossible to take you, the young-guy thrill-kill action fans, or the hardcore, aerial-ballet Hong Kong genre that you love seriously any more, but I do feel three things…ready? I am genuinely aroused by the challenge of constructing great action choreography, purely as a technical exercise. But it does nothing more than amuse me, and my basic attitude is one of laughing derision for the whole Woo-aping circus. ”

Most high-octane urban thrillers do the same old double-track — half trying to excite audiences with extremely well-choreographed violence and half winking at them with self-referential goofery. Davis is almost doing this, but at the same time he isn’t. He pushes the action antics and the hard-boiled genre attitudes to such extremes that he’s made the next thing to a Road Runner cartoon.

And I loved it. I loved that Davis is simultaneously good at this crap but at the same time is anything but a devoted churchgoer. He doesn’t give a shit about the genre (not really, not in a true-disciple way), and is unable to invest anything of himself in the story, which is another one of those stories about a lethal lone wolf with a damaged soul trying to do a good deed, which goes all the way back to Shane.

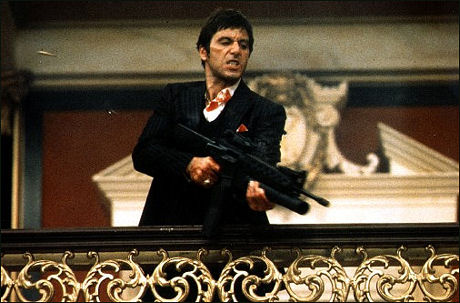

(l. to r.) Owen, Bellucci, director Michael Davis

Shoot ‘Em Up is emphatically not the grindhouse movie that Harvey Weinstein thought he was going to get when he gave free reign to Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez. Those guys really love high-kicking action movies and all the pulpy fever that goes with them. Davis, by contrast, is a very clever elitist in a silk smoking jacket who is 40% disgusted and 60% howling with laughter at this type of thing. He’s obviously good natured and energetic and clearly loves to make a film rip all over the place, but he’s not into “explosions.” He’s too excited by dry, low-key wit and the joy of writing awful action-movie puns to do the usual-usual.

Davis, in short (or so I believe), can’t be bothered to aspire to the class of Tarantino, Rodriguez, Michael Bay or Live Free or Die Hard helmer Len Wiseman. He would probably be very depressed to be regarded as “one of those guys.” I honestly feel that he’s above them, and coming from a much more interesting place. The invisible subtitle of Shoot ‘Em Up, after all, is Contempt.

I read the Shoot ‘Em Up script in March 2005, and it felt at the time “like a great New Line genre film in the tradition of The Hidden, the first Rush Hour, Blade and so on. It’s fast, punchy, sardonically funny, and aimed at younger guys and connoisseurs of action choreography-for-its-own-sake.” I was partly right and partly wrong in saying that. It is nothing like Rush Hour or Blade. It’s a little like The Hidden, but only a bit.

“The crusty, cynical noir-flavored tone is familiar, but the big action scenes have a kicky ‘haven’t been here before’ quality,” I wrote. “They take the Hong Kong Woo aesthetic to absurd new heights, but in a way that feels freshly insane, oddly logical and edgy-funny. It’s screwball formula nihilism with a twist.” That’s a little closer to the mark.

Shoot “Em Up isn’t just the work of director-screenwriter Davis. As I’ve heard it, it’s very much a collaboration between himself and king-shit producer Don Murphy along with tadpole producers Susan Montford and Rick Benattar. Editor Peter Amundson was also a major player. They had to go back and shoot extra footage, and so what? It was worth the effort.

The soul of Shoot ‘Em Up is in the constant editorial asides when Owen goes “you know what I hate?” and he goes off on numerous aspects of modern life that greatly piss him off. Belligerent rich guys who drive black Mercedes coupes but can’t be bothered to flip a turn signal, for instance. My favorite comes when he slaps down a fat guy who’s been sipping soup and going “aahhh” after every slurp. (I hate guys like that myself. So much so that I’ve told myself for years whenever I’m eating soup to not slurp and not go “aaahhh.”)

But the biggest “you know what I hate?” in Shoot “Em Up isn’t spoken in so many words. It’s in every scene of the film, and not hard to discern.