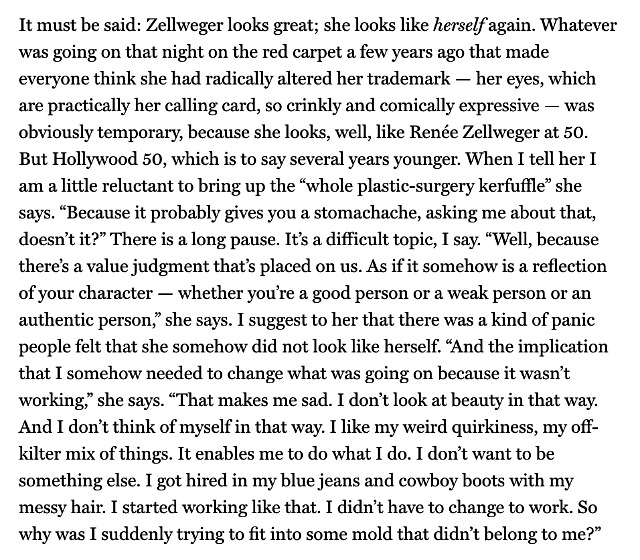

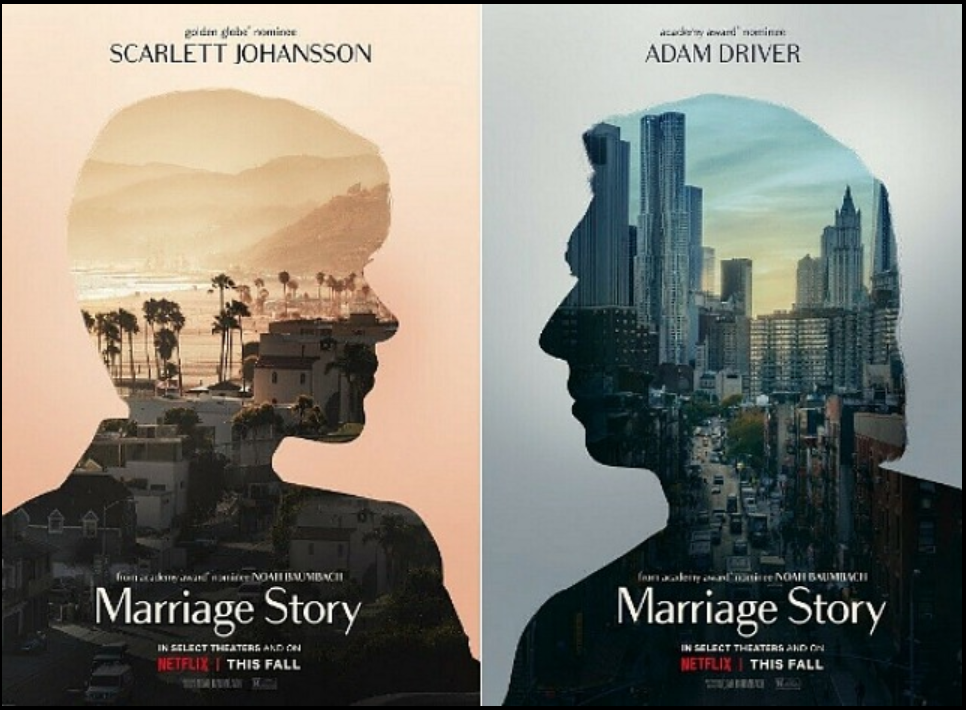

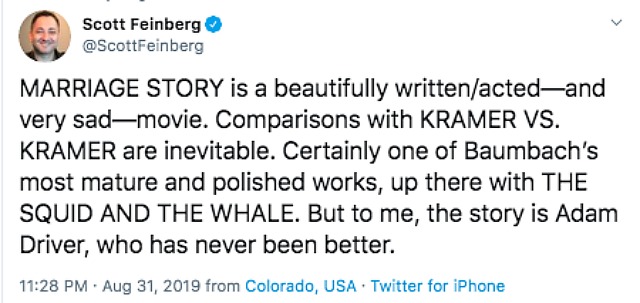

I finally caught Noah Baumbach‘s Marriage Story Saturday evening. With all the buzz I was more or less expecting the moon, I suppose, but I wasn’t disappointed. It didn’t quite melt me down like Kramer vs. Kramer did 40 years ago, but it sure softened me up. Which it to say I felt “met” on adult terra firma, and within a fully recognizable realm.

It’s more Ingmar Bergman than Robert Benton-esque. But sensibly so. Like all fine, steady, smart films that open between October and December, Marriage Story delivers the goods in a way that seems to fundamentally apply. It’s “one of those.” And I didn’t think of it as Black Widow vs. Kylo Ren. Well, if their defenses were considerably lessened.

I felt vaguely unsure where it was going or what it was up to a couple of times, but I mainly felt like I was in good, safe hands — gripped, touched, respectful, comfortable (because it never goes crazy or overly dark, it never breaks the trust) and always recognizing the truth of what’s on the plate.

Marriage Story is easily Baumbach’s best film, above and beyond The Squid and the Whale, and surely contains the best, most fully felt, deep-from-within performances that Adam Driver and Scarlet Johansson have given thus far. It’ll be really, really difficult for them to top this.

Best Picture nom, Best Director/Original Screenplay noms (Baumbach), Best Actor and Actress (Driver, ScarJo) and maybe a Best Supporting Actress nom for Laura Dern because of a single, third-act rant she delivers about society’s unfair attitudes toward women in terms of idealized “male gaze” expectations, and probably a nomination for composer Randy Newman.

The costar performances are just right — Azhy Robertson as Henry, Alan Alda and Ray Liotta as attorneys with radically different styes, Merritt Wever, Julie Hagerty, et. al.

It’s an honestly felt, emotionally complex (and sometimes convulsive) marital-downswirl drama, but with a rather middle (moneyed) class attitude…acrimony tempered by sensible sensibilities. Fundamentally decent people with the usual issues and shortcomings, but nobody’s a raving lunatic Nobody throws up or gets busted in some lewd, embarassing infidelity or throws a frying pan or drives a car off a bridge or runs naked into a traffic jam.

Driver and ScarJo are the married, Brooklyn-residing Charlie and Nicole, the latter a successful theatre director and the former his star performer who feels overshadowed by Charlie’s egocentric attitudes and looking to possibly re-launch her acting career in Los Angeles with a promising TV series.

Read more