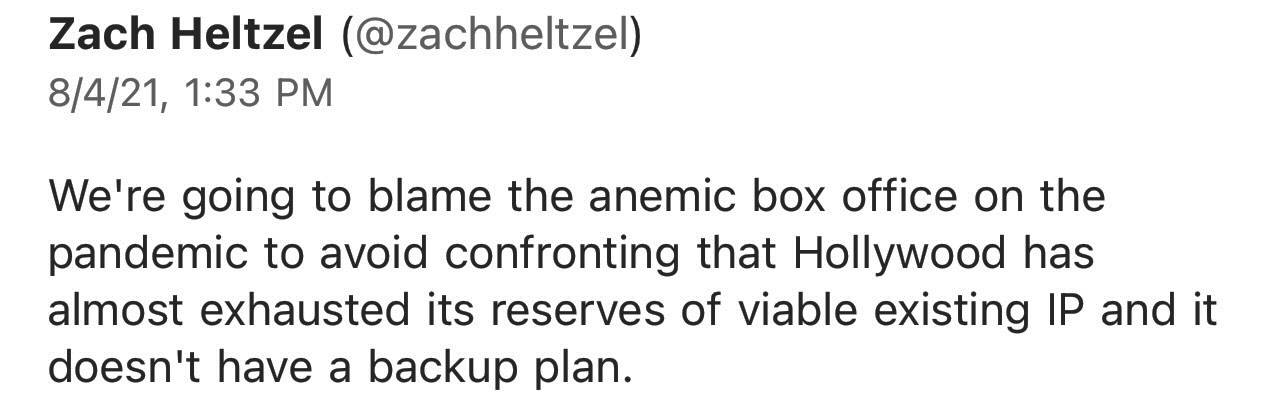

Variety‘s Adam Vary to The Suicide Squad director James Gunn: “With Peacemaker and The Suicide Squad both on HBO Max, you’re right at the heart of the massive changes the industry is going through with the rise of streaming. People don’t even quite know what a movie is anymore, or where they’re going to get exhibited. How do you see yourself fitting into all that moving forward?”

Gunn to Vary [following “long pause”]: “I don’t really care that much. I really just care about whatever the project is in front of me. The Suicide Squad is made to be seen first and foremost on a big screen [but] I think it’s gonna work just fine on television.

“Listen, movies don’t last because they’re seen on the big screen. Movies last because they’re seen on television. Jaws isn’t still a classic because people are watching it in theaters. I’ve never seen Jaws in a movie theater. It’s one of my favorite movies.

“I…don’t want the theatrical experience to die. I don’t know if that is possible, but we also don’t know what’s going to happen. We’ve still got COVID, because people won’t get vaccinated, which, you know, they should. Hopefully — hopefully — that will not be a big deal to us in a year. And if that’s the case, what’s going to happen? We don’t know. Nobody knows.

“I care, because I would rather have people be able to go to the movies. But also, if they don’t, I’m not going to go slit my wrists. I don’t care that much. [Laughs]”

Hollywood Elsewhere feels the same way, after a fashion. I don’t want big-time movie exhibition to die, but when I think of the theatres that I really care about, I think of the Landmark chain and what the Arclight chain used to be, and of course the special theatres in Telluride and Cannes. Because I basically hate the gladiator movies that are occupying and dominating the magaplex stadiums these days. You go to these places to get thrashed and pounded.

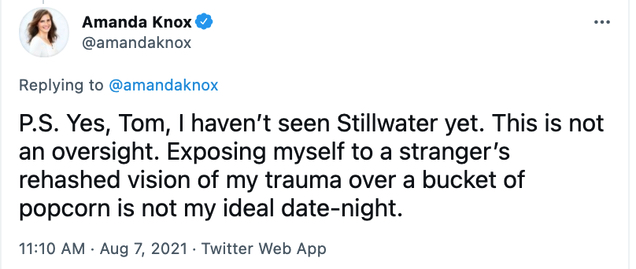

Which is why it felt so weird to watch Stillwater at the AMC Century City recently. I was muttering to myself, “Jeez, I’m watching a carefully measured, character-driven adult drama inside theatre #9, which almost exclusively shows animal-level, wham-splat ear and eye–pounders…odd feeling. Hey, where’s Amanda Knox?”

Gunn is right, of course, about certain well-reviewed movies and various classics of the past enduring via streaming platforms. Streaming is obviously how all great movies are being kept alive these days, as well as providing a platform for fresh discovery.

Yes, the exhibition industry has been losing steam for a few years now, in part because theatres have become a digital ghetto for noisy, high-impact, lowest-common-denominator fare.

But until late ’19, exhibition was still the primary place where all movies began. Theatres were the primary default launch pad. Big-screen exposure and promotion established their presence and cultural impact. Theatres mattered less, but they still mattered.

I’m somewhere between depressed and horrified by the idea of a movie realm without theatres. And not just my kind of theatres. As much as I despise the gladiator experience, I want it to survive, ironically, in order to keep exhibition going in general.

In short, I might care about theatres more than James Gunn does. Unless I’m misunderstanding him.