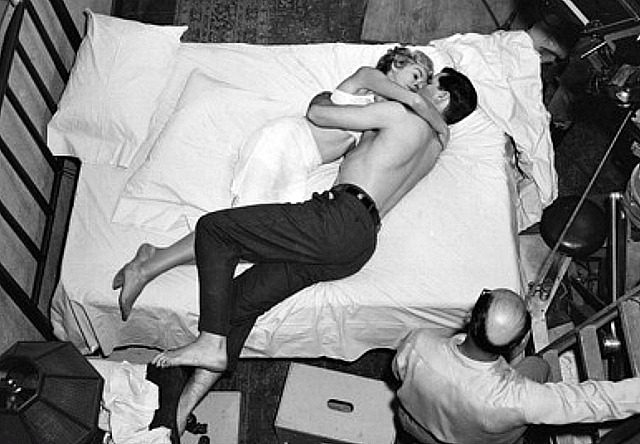

Yesterday the combined forces of Steven Gaydos and “Norton Ghomestead‘ tried to discredit a popular notion that Pauline Kael’s epic-sized New Yorker rave of Bonnie and Clyde was a key factor in that 1967 film’s revival, following a dispiriting late-summer release.

Ghomestead maintained that “Warner Bros. promotion guys, realizing that savvy showmen in the south were doing well with [Bonnie and Clyde] as a Thunder Road-like tale of high spirited lawbreaking, smartly capitalized on that [and thereby gradually] made it a hit”.

Gaydos reposted his 2003 Variety piece (“Truth takes bullet with Clyde tale”) which basically said that the legend about Kael’s review is not supported by research and that the film gradually became a hit through old-fashioned blood, sweat and tears — i.e., the promotional kind.

HE reply: I see. Thanks, guys, for straightening me out. So to sum up (and please correct me if I’ve got this wrong), Pauline Kael’s landmark reassessment in The New Yorker had little if anything to do with saving Bonnie and Clyde. Instead it was the Warner promo guys re-selling it as a “Thunder Road-like tale of high-spirited lawbreaking” to redneck audiences.

A film inspired by the French New Wave, a film that was clearly ahead of its time, a film that Francois Truffaut was initially interested in but passed on, a film with an art-filmy impressionistic sequence when Bonnie and Clyde visit her frail old mom, and another when they’re found wounded and bloodied by Okies,,..this alternately edgy and poignant film was reborn when WB sales guys pitched it to Nehi Cream Soda-drinking yokels. So Pauline Kael was incidental at best. Got it. Check.

I’ll accept the Gaydos assessment — “Bonnie and Clyde [was] carefully nurtured from Montreal to Manhattan with both studio and private promotion, solid reviews and solid business and given time to build into a breakout hit just as dozens of other films of the era had” — blended with the impact of the Kael piece, but that’s as far as I’ll go.

Without tossing out the redneck promotion side-story, the likeliest scenario is that Beatty saved the film (and his own financial ass) by refusing to back off in his dispute with the antagonistic Jack L. Warner, to the point of threatening legal action.

Wiki excerpt: ” At first, Warner Bros. did not promote Bonnie and Clyde for general release, but mounted only limited regional releases that seemed to confirm its misgivings about the film’s lack of commercial appeal.

“Beatty, Bonnie and Clyde‘s producer and star, complained to Warner Bros. that if the company was willing to go to so much trouble for Reflections in a Golden Eye (they had changed the coloration scheme at considerable expense), their neglect of his film, which was getting excellent press, suggested a conflict of interest; he threatened to sue the company.

“Warner Bros. gave Beatty’s film a general release. Much to the surprise of Warner Bros.’ management, the film eventually became a major box office success.”