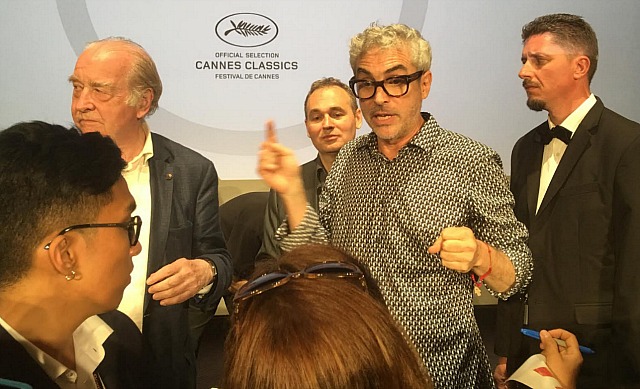

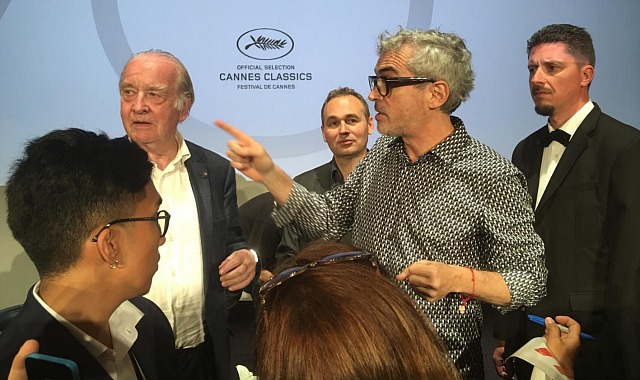

Late this afternoon I attended an Alfonso Cuaron Masterclass in the Salle Bunuel, which was basically the renowned director of Y Tu Mama Tambien, Children of Men and Gravity sitting for an 85-minute interview with French film critic and author Michel Ciment. [A full recording is at the bottom of this page.] They discussed Cuaron’s career — chapter by chapter, film by film — and showed clips. Fine.

And yet Cuaron’s upcoming Spanish-language Roma, which he shot last fall and is basically about a year in the life of a middle-class, Mexico City family in the early ’70s, wasn’t even mentioned. Which disappointed me. I attended this interview not to hear Alfonso talk about Y Tu Mama Tambien or that fucking Harry Potter film or Sandra Bullock or the blood splatter on the lens in Children of Men for the 47th time, but to hear Cuaron speak about Roma at least a little bit…c’mon! Would it have killed him to discuss what it is and what he’s going for, to allude to the story a bit and maybe discuss the tone, themes and whatnot?

I asked Alfonso if there’s any chance of Roma coming out by the end of ’17, and he said “noahh…I didn’t make it.” Maybe it’ll show up at next year’s Cannes Film Festival (an especially good place to launch any quality-propelled, non-English-speaking film), he allowed. Or maybe a year from next fall….who knows? But what a drag that he didn’t even allude to it.