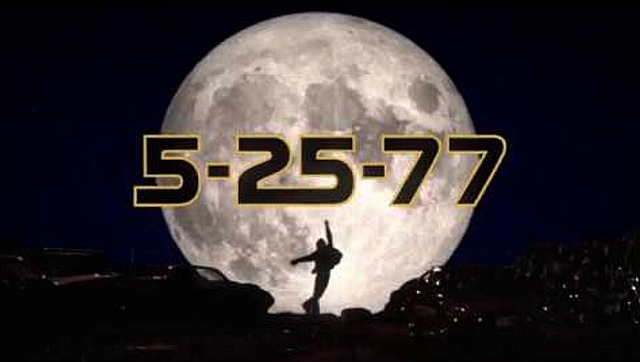

Patrick Read Johnson‘s 5-25-77, a flawed nostalgia flick that was shot 13 years ago (actually between ’04 and ’06) but has never been released, screened in 32 theaters last Thursday night to honor the 40th anniversary of the opening of Star Wars. It will likely stream on Filmio before the end of the year, I’m told. A friend who caught a screening at the Laemmle Wilshire shares the following:

“It’s a sweet film, and I obviously respect Johnson’s passion and perseverance. Is it unwatchable? No. But it definitely feels amateurish at times. Like a clever home movie. The Star Wars thing is really only half the movie but the point is that Star Wars could be a stand-in for anything. Whatever you’re passionate about and makes you obsess. Ultimately, the story just isn’t there though. I enjoyed myself [as far as it went], and admire the film as a labor of love, but you didn’t miss anything.”

From a director-screenwriter friend: “Well past the expiration date, just like Kyle Newman‘s Fanboys. Rob Burnett‘s Free Enterprise already nailed this culture. A friend pointed out how the 5-25-77 protagonist’s mother pours through American Cinematographer calling people in Hollywood to get her son a job. But it should’ve been him doing the calling. Too passive a character. That’s the real problem.”

Brigsby Bear‘s Kyle Mooney, Greg Kinnear — Thursday, 5.25, 1:40 pm.

Brigsby Bear‘s Kyle Mooney, Greg Kinnear — Thursday, 5.25, 1:40 pm.  (l. to r.) Brigsby Bear co-writer Kevin Costello, director Dave McCary, Wrap correspondent Ben Croal during Thursday luncheon at Silencio.

(l. to r.) Brigsby Bear co-writer Kevin Costello, director Dave McCary, Wrap correspondent Ben Croal during Thursday luncheon at Silencio. Brokeback Mountain commentary sent to HE by Costello 11 and 1/3 years ago, when Costello was an Oklahoma resident.

Brokeback Mountain commentary sent to HE by Costello 11 and 1/3 years ago, when Costello was an Oklahoma resident.