Update (7.28, 6:30 am): The W. trailer was pulled from You Tube sometime last night — great while it lasted. Original post: “What are you cut out for? Fighting, chasing tail, driving drunk? What do you think you are? A Kennedy? You’re a Bush. Act like one.”

Lionsgate has been chasing down an illegally posted W. trailer all day on various sites. I don’t know why. It’s pretty good stuff. They probably want to get a better-looking high-def version out there instead of a bootleg. It’s still playing on You Tube as we speak (minus the embedded code).

Crotchety Old Coot

“Once again he was making factual errors about the only subject he cares about, imagining an Iraq-Pakistan border and garbling the chronology of the Anbar Awakening. Once again he displayed a tantrum-prone temperament ill-suited to a high-pressure 21st-century presidency. His grim-faced crusade to brand his opponent as a traitor who wants to ‘lose a war’ isn’t even a competent impersonation of Joe McCarthy. Mr. McCain comes off instead like the ineffectual Mr. Wilson, the retired neighbor perpetually busting a gasket at the antics of pesky little Dennis the Menace.” — from Frank Rich‘s 7.27 N.Y. Times column, “How Obama Became Acting President.”

Where The Money Is?

Yesterday Patrick Goldstein reiterated a common observation (which was initially stated on 7.15 by Variety‘s Anne Thompson) that Paramount Vantage’s decision to replace production and acquisition exec Amy Israel with ex-New Line exec Guy Stodel, the Texas Chainsaw Massacre franchise-revival guy, means that Vantage is about to be “turned into a Screen Gems-style genre division.”

As Goldstein correctly pointed out, the Stodel hire is an expression of a creaky philosophy. If you want to really make money, the thinking goes, resuscitate the spirit of Irwin Yablans by making movies for the mongrel element. Enough with the artsy-fartsy upscale stuff and make movies that sell popcorn to the genre geeks and the shaved-head guys who wear Foot Locker sneakers.

The problem is that lowball comedies, thriller and horror pics almost never deliver the magic — they aren’t intended to — and a too-heavy emphasis on lowball elements can make a distributor smell a little skanky after a while. Most people go to movies with the notion that something spiritual might happen — that they might end up knocked back or levitated out of their seats. We all go to films for the first-class stuff, whatever form it may come in. Leaving aside sophisticated genre-wallowers like Quentin Tarantino, only the bottom-of-the-barrel types go to movies to have their gut-level cravings sated.

The basic philosophy of any good filmmaker should be that dreams transport because they’re better than real life. If you don’t believe that, you don’t really believe in movies.

Shia LeBang

After posting a 5.17.08 story about meeting the Indy 4 gang at the Carlton hotel during the Cannes Film Festival, some of the talkback yentas slammed me for trying to pay a compliment to Shia Lebeouf. “I told LeBeouf he looked great also, adding — this was a minor mistake — that the program obviously agreed with him,” I wrote. “‘The program?,’ he asked. ‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘AA….no? I read you’d gone into the program after the Chicago Walmart bust.’ Lebeouf looked a little alarmed. ‘Nope…no program,’ he answered. ‘Just livin’ my life.'”

I interpreted “just livin’ my life” to mean that Lebeouf didn’t feel he had a problem that needed addressing so why not just chill and have a good time? Except today’s news about Lebeouf getting popped for a misdemeanor DUI following a 3 am car-banger in Hollywood suggests there may in fact be a behavior issue he needs to address. This on top of the Chicago Walgreen’s bust, I mean. Lebeouf reportedly told David Letterman that “drinking and driving is one thing, but drinking and shopping [is] just as bad.”

Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Sgt. Scott Wolf said this morning “it was immediately apparent to officers responding on the scene that LaBeouf was intoxicated and he was subsequently placed under arrest.”

In hindsight I would say I was getting down to business with Lebouf by mentioning the “program” and offering support and encouragement about same (however ignorant I may have been about his involvement with AA), so I would say I was more right than wrong, more generous and positive-minded than not.

McCarthy vs.Thunder

Wait…Variety‘s Todd McCarthy has panned Tropic Thunder? Something is funny or it isn’t, but wow…what a gulf. One man’s comedic delight is another’s torture chamber.

San Diego Blahs

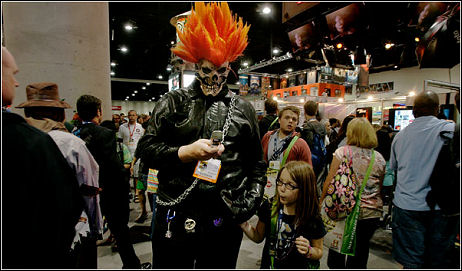

A geek dad in a monster outfit hanging with a toddler…right. A variation on the generic Comic-Con photo that runs in the N.Y. Times each and every year. I’m not putting the practice down. I would run this photo (or one like it) if I’d been asked to decide which photo would best go with this Michael Ceiply story about Frank Miller talking about directing The Spirit, which we all know will be trotting out the same Frank Miller routine — high-style CG noir mixed with tough talk, slinky dames and ripe sensuality.

Warning

I shared an observation about four or five years ago that I’m now going to repeat, to wit: this is one of the best movie endings of all time — right at the top of the list, I’d say. It’s great and mythic because (a) it explains exactly what the film has been about (i.e., the spreading U.S. paranoia about commies, UFOs and other usurpers of the American dream) without getting preachy, and (b) strongly hints that the worst of the bad stuff is yet to come. And then that hard-slamming Dimitri Tiomkin brass…brilliant!

Aronfosky + Robocop

The brilliant, avant-garde-ish Darren Aronofsky doing a Robocop film? Good God. The sensitive New York director of the brilliant Pi, the intensely druggy and degenerative Requiem for a Dream and the trippy-mystical The Fountain? Lo, how the mighty and gifted have fallen. Wait…The Wrestler with Mickey Rourke?

On the other hand there’s the relatively recent reality of Aronofsky becoming a dad, and the likelihood of his not wanting to be seen as the esoteric guy whose films don’t play to the mongrel popcorn crowd, and so what the hell…he takes a straight paycheck gig. The upside is that this will be the brainiest Robocop ever. The fact David Self (Thirteen Days, Road to Perdition) is doing the screenplay indicates something non-cheesy.

Clinton Edges out Bush

Big Picture columnist Patrick Goldstein has missed the big picture in his 7.25 article about screenwriter Peter Morgan‘s third and presumably final Tony Blair movie, the first two being The Deal and The Queen. Goldstein said that Morgan “envisions the script,” called The Special Relationship, as “an intimate portrait of Blair’s relationship with Clinton, circa 1997-2000.”

Peter Morgan, Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, George Bush

Well and good, but what Goldstein doesn’t mention is that the script was first envisioned as a tragic tale of Blair’s downfall due to his misguided alliance with Bush over WMDs and the mounting of the Iraq War. Michael Sheen, who portrayed Blair in The Deal and The Queen, told me in the spring of ’07 about Morgan’s plan to eventually write a Blair-goes-down movie (and about his expectation that he would star in it).

On 10.1.07 Variety‘s Adam Dawtrey reported that the new movie will focus on Blair’s “reaction to the handover of power from Clinton, a natural liberal ally, to Bush, who came from the other end of the political spectrum, which Morgan sees as a pivotal moment when the special relationship between Britain and America changed.'”

What’s happened, in short, is that Morgan has gradually lost interest in the Bush-alliance downfall story and shifted focus to the lah-dee-dah Blair-Clinton relationship. It’s almost certain that whatever A Special Relationship turns out to be, Morgan will make it work and then some. He’s a very sharp writer. But I for one am disappointed. The Iraq War-downfall thing is about a smart guy going astray, drinking the Kool-Aid and screwing his career — clear and simple. What’s the Bush-Clinton story about? Two liberal-minded heads of state come to like each other during the ’90s and….what? I don’t see what it is.

Harsh Words

N.Y.Press critic Armond White has delivered a blistering critique of Nanette Burstein‘s American Teen. As in, “If American Teen had smell-o-vision, the scent of bubble gum would be overpowered by crap.” I’m not posting this to signal agreement; I just enjoy White when he goes on a tear.

“Don’t fall for the capturing-real-life ruse,” White cautions. “That’s a Heisenberg Principle trap (asking us to excuse the filmmaker’s cynicism, since we already realize her presence). It’s no different from Christopher Nolan‘s cynicism in The Dark Knight: The graduating students of Warshaw High suggest suburban comics heroes: Zit Boy, Tramp Girl, Manic Twat, Texting Dork, Jock Dweeb. Without any emotional or historical context for these pathetic youth, Burstein merely offers a spectacle of chipmunky kiddie voices and garbled diction.”

Watchmen at 180?

Watchmen director Zack Snyder “is currently battling Warners over the ultimate running time of his film, which is three hours,” reports Variety‘s Anne Thompson from Comic-Con. “He’s trying to cut it down, but doesn’t want to lose a character like Hollis, a guy who gets murdered about half way through.

“‘I’m not ready for that yet,” Synder says. ‘If Dark Knight got two and a half hours, Watchmen should get fifteen minutes more. I’m trying to be reasonable.’

“Snyder is caught between the Scylla and Charybdis of the studio’s commercial demands and the fans who love the comics,” Thompson remarks. “A movie has to reach beyond the faithful, remaining accessible to mainstream moviegoers.”

This reminds for some reason of a 1994 Daily News headline that bannered an interview I did with Wyatt Earp director Larry Kasdan, to wit: “Draw At Count of Three, Wyatt….Hours!”

Today’s Watchmen presentation is the only Comic-Con thing I really wanted to see. But I wasn’t going drive all the way down to San Diego just to do that.

Prayer

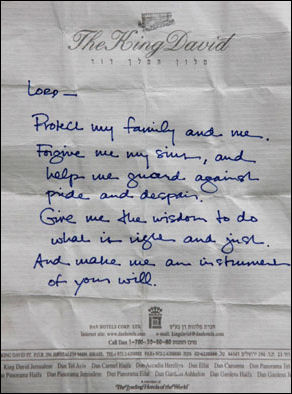

Cinemascope‘s Yair Raveh has passed along Barack Obama‘s handwritten prayer note, written on hotel stationery, that the Democratic presidential candidate slipped between the stones at Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall during his visit to the site two days ago.

“Journalists then promptly stormed the wall and ransacked his note,” he writes. It turned up in today’s issue of Maariv, a popular Hebrew-language daily. “It’s a big faux pas from a Jewish traditional point of view to steal a written Wailing Wall prayer,” Raveh writes, “and I’m quite certain that if Obama were Jewish no mainstream reporter would’ve dared violate his privacy so bluntly.”