As they finish post-production chores on No Country for Old Men, which will play at Cannes next month, Joel and Ethan Coen are making it known that their next two films will come out of a new deal with Focus Features and Working Title. The first, which will begin shooting this summer, is called Burn After Reading, and will costar George Clooney, Brad Pitt (as a gym trainer) and Frances McDormand. This will be followed by A Serious Man, which was reported by Variety‘s Dade Hayes as being “a dark comedy in the vein of Fargo.” If anyone has either script, please get in touch and we’ll do a trade.

Yelstin is dead

I was so caught up in the drama of Carina Chocano a few hours ago (which turned out to be not so dramatic) that I missed the late-morning news about the death of Boris Yeltsin. He was the first Russian leader I genuinely admired (or half-admired), and I think he’s also the last one to qualify in that regard.

Yeltsin was a brave, erratic man, a fighter, a moody reformist, a drinker (which led to health problems), charismatic and bear-like…the guy whose best moment came when he stood up on that tank in August 1991 and rallied the Soviet people against an attempted coup against the government of Mikhail Gorbachev, “a heroic moment etched in the minds of the Russian people and television viewers all over the world,” as Marilyn Berger‘s N.Y. Times story reads.

“Although his commitment to reform wavered, Yeltsin eliminated government censorship of the press, tolerated public criticism, and steered Russia toward a free-market economy,” Berger wrote. “Not least, Yeltsin was instrumental in dismembering the Soviet Union and allowing its former republics to make their way as independent states.”

Carina Cocano demoted?

There was an item saying that L.A. Times film critic Carina Chocano had allegedly been “taken off duty” by her editors and given a weekly opinion- analysis column in the Sunday edition. I called six or seven people and heard nothing, then someone finally called to explain. The deal is that Chocano hasn’t been kicked off the beat as much as subjected to a kind of editorial experiment. Plus she got married recently (i.e., out of the country) and has been honeymooning. Plus, I’m told, she’s going to be reviewing again starting Friday.

The Anne Thompson item that started the rumpus made sense on the face of it since it sounded like another L.A. Times cost-cutting measure — a very common thing these days when discussing the most miserable and self-torturing newspaper on the face of the planet. Other reviewers Kevin Crust and perhaps a freelancer or two (Sam Adams?) have stepped in during Chocano’s abscence, and will presumably keep their hand in.

If the Times is looking for alternate freelancers, how about City Beat critic Andy Klein for some pinch-hitting? One of the smartest and most knowledgable critics on the planet, and a guy who writes in a nicely honed, plain-talk style.

Chocano is a very smart and skilled writer, and for what it’s worth her reviews have always seemed fairly engrossing to me. I like her the way I like Anthony Lane, although his reviews are funnier and more deftly phrased. But Chocano has never been accepted by the film-critic elite as being “one of us,” or at least she wasn’t when she first landed the Times film-critic gig. Some had bristled about her TV criticism background and the suspicion that she hadn’t paid her dues the way the hard-core monks have. And others have said they’re not big fans of her reviews, but I’ve always taken these views as expressions of political discontent.

“I actually came to like her stuff,” an L.A. Film Critics Association member told me a few minutes ago. “I gradually came around. She hasn’t applied for membership in LAFCA and I don’t know what that’s about, but I don’t see that much resentment towards her these days. That was before, I think.”

Bad gunfire

If you care about westerns or urban action movies, you care about the sound of gunfire. I love it when a filmmaker takes the time and effort to make the old blam-blam sound exactly right, or in some better-than-real-life way (like Michael Mann did with Tom Cruise‘s pistol shots in Collateral). And it always turns me off when gunfire sounds wrong. This hardly happens any more, but I was reminded last weekend as I watched John Sturges‘ The Magnificent Seven what really bad gunfire sounds like.

Then I remembered that I wrote about this very topic close to six years ago, so here ‘s the piece again. I’m figuring some of the present-tense readers weren’t around back then, so here, in honor of Nick Nolte‘s journalist character in I Love Trouble, is a Reel.com re-run.

“Good work has gone into MGM Home Video’s DVD of The Magnificent Seven,” I began. “The 1960 Western didn’t create a huge stir initially but has since become a kind of cult flick, particularly beloved by boomer critics and filmmakers who were kids when they first saw it.

“But the sound of the gunfire in this film is wrong. I would even say irritating. Every time an acto rin that film shoots a rifle or a handgun, we hear the exact same report — a three-syllable sound that phonetically translates as ‘guh-BACH-owhl.’ Most of you know this sound. You’ve heard it in a hundred other westerns (cheaper ones, usually) and ‘guh-BACH-owhl’ is its name.

“I’ve shot pistols and rifles and M-16s and machine guns, and none of them went ‘guh-BACH-owhl’ when I pulled the trigger. They usually go “Bauhlnt!” but shortly, succinctly. Another sound I’ve heard from live guns is “Puhng!”

“One of the least accurate-sounding gunfire recreations you’ll ever hear on a soundtrack is in George Stevens‘ Shane, although it’s absolutely one of the coolest. The guns in that film roar like cannons inside an echo chamber. Warren Beatty once said in a documentary about Stevens’ life (George Stevens: A Filmmaker’s Journey) that he tried to recreate this same sound for Bonnie and Clyde.

“Beatty understood how great the Shane guns sounded and cared enough to make the effort to reproduce them. Sturges never went that deep. There are about 145 ‘guh-BACH-owhl’ shots in The Magnificent Seven, and by the time you hear 40 or 50 it starts to get bothersome. I don’t mean to sound petty or obsessive, but when you’re doing a Western you have to get this stuff right.”

“Star Wars” again

The fanboy factor has resulted in a buy-out of tickets to tonight’s 30th Anniversary screening of Star Wars at the Motion Picture Academy. But “due to attrition, no-shows and cancellations,” a certain quantity of seats should be available to pikers in the stand-by line. People like myself, I mean.

I’d like to attend because producer George Lucas will be doing a q & a after the screening along with other members of the team, but I’m not sure if my withered sense of dignity will allow me to wait in line for 90 minutes or more to see a 30 year-old film that I’ve always regarded as, at best, an okay diversion. (It would be a different story if The Empire Strikes Back were showing.)

The Academy website doesn’t say whether they’ll be showing the 1977 original or the digitally augmented “Greedo shoots first” version, but Academy spokesperson Leslie Unger told me a while ago it’ll definitely be the digitally augmented version.

It can probably be safely assumed that a mint-condition version of the 1977 original will never be shown at a first-class theatre ever again. Wasn’t the recently released DVD of the ’77 version taken from an old laser-disc master from the ’90s? Lucas couldn’t be bothered to restore it or even tweak it up.

Masters on “Spider-Man 3” budget

Despite an angry studio publicist’s denial, Radar‘s Kim Masters is reporting in a just-up Radar piece that Spider-Man 3 (Columbia, 5.4) has surpassed 1963’s Cleopatra as the most expensive movie ever made. With the enthusiastic go-go support of Sony chairperson Amy Pascal, Sam Raimi‘s third and presumably final Spider-flick cost $350 million, she writes, compared to Cleopatra‘s inflation-adjusted budget of $290 million.

Add a guesstimated $150 million in marketing costs and Spider-Man 3‘s final tally will be $500 million, according to Masters’ calculations.

Spider-Man 3 is pretty much ding-proof — the fanboys are going to break down the doors no matter what — but Masters’ article will muddy the waters. Add this to the so-far tepid reviews and the spreading awareness and/or growing prejudice that revved-up, cranked-up CG extravaganzas are dead-end sits because of their constant war between their two halves (being 50% exciting in an obvious thrill-ride sense and 50% numbing in a sensory-overload sense, which leads to 100% depression by the time the third act rolls around), and the stage is set for U.S. ticket-buyers to go into it with a skeptical, perhaps even bordering-on-sourpuss attitude.

An absurdly expensive movie of this proportion — whether it cost $270 million or $300 million or more — means at the very least that Spider-Man 3 was a huge corporate pig-out for all the major creative players. And now you, Mr. and Mrs. Paycheck, are expected to show up at theatres on May 4th and pay your ten bucks so the machine can keep rolling and all the fat players can go to the trough again and again. Keep it rolling, keep it rolling…support the elite Hollywood profligates! They would be lost without you.

“On the surface, Spider-Man 3 has all the ingredients of a box-office slam dunk — √É‚Äö√Ǭ≠spectacular special effects, an obsessive fan base, and a roster of bankable stars,” Masters writes. “Moreover, its two previous installments have grossed $1.6 billion for the studio.

“Even before filming began in January 2006, [director] Sam Raimi promised to pull out all the stops for his third Spidey film (likely the last he’ll direct in the series). He wasn’t kidding. As production dragged on into late summer (it had been scheduled to conclude in June), stories about the project’s ballooning budget started popping up all over town. But in the end, even the most hyperbolic of observers may have underestimated the final tab.

“Industry insiders claim that Sony spent $350 million or more on production alone. With marketing and promotion factored in, the total price tag will approach half a billion dollars, positioning Spider-Man 3 as the most expensive movie of all time.

“Still reeling from a flurry of bad press on its PlayStation 3 gaming console, Sony isn’t eager to claim this honor. A studio spokesman angrily rejects the $350 million estimate as a ‘complete fabrication,’ insisting that production costs didn’t exceed $270 million. One of the film’s producers, Laura Ziskin, also disputes the higher total, albeit in a less forceful manner. “I refuse to say the [real] number because it makes me choke,” she tells Masters. “Spider-Man 3 was a super- expensive movie — the most expensive film we’ve ever made. But there’s no way you can get to $300 million.”

“Reports of Sony’s record-breaking gamble have created a stir among entertainment insiders, seeming to evoke some combination of schadenfreude and envy. “Those are crazy numbers,” remarks one leading industry figure.

“I don’t think this sets a great [precedent] for any of us,” complains a top executive at a rival studio. “It’s beyond the beyond. The problem isn’t that other studios will now feel liberated to drop $300 million on a movie. The real danger is that it makes the $200 million movie seem not quite so bad. And the risks of that can be absolutely devastating.”

“Noting Sony’s long and storied history of overspending, the head of another studio asks, “Where is the corporate oversight? Who’s demanding accountability? How is it that they’re repeatedly able to conduct themselves in this manner?”

“To be fair, Sony is hardly the only studio spending big bucks on tent-pole projects. Shrek the Third blows into multiplexes two weeks after the new Spidey film, with Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End right behind it. Next come the Fantastic Four sequel and Steve Carell‘s Evan Almighty. Then, on Independence Day weekend, Transformers hits the screen.

“None of these projects was cheap. Indeed, the third installment of Pirates may also sail past the $300 million mark. But in contrast to the Spider-Man series, the second Pirates film outperformed the original and grossed more than a billion dollars. (Spider-Man 2 took in $783 million, or about $40 million less than its predecessor.)

“Sony’s free-spending ways have been evident ever since the Japanese electronics giant acquired Columbia Pictures in 1989, causing much consternation among competitors who feel pressure to match the studio’s largesse. The first chairmen in the Sony era, Jon Peters and Peter Guber, spent so much money that the studio wound up taking a $3.2 billion write-down. The two were eventually fired, but business continued as usual. In 1996, chairman Mark Canton blew the roof off star salaries by awarding Jim Carrey an unprecedented $20 million for his role in The Cable Guy, a film that disappointed at the box office. Soon after, Canton was also gone.

“To many observers, though, the budget for Spider-Man 3 represents a terrifying new frontier, even for Sony. As other studios try to cut costs, Pascal has continued in Sony’s profligate tradition.

“The only woman currently heading up a major studio, she also happens to be one of the most popular executives in the business,” Masters concludes. “That’s largely because she seems to have a genuine love for movie-making at a time when many of her peers are fixated on the bottom line. ‘Amy’s greatest strength is her intuitive, creative ability,’ says a longtime associate. ‘Her greatest weakness is that she lets that same ability get completely separated from any sense of fiscal restraint.'”

Zinneman and “Jackal”

Was there any film that was truly, madly and absolutely Fred Zinneman‘s? He did High Noon proud, but that 1952 western wasn’t Zinneman’s as much as it was screenwriter-producer Carl Foreman‘s. From Here to Eternity was well assembled by Zinneman, but it’s hard to see him as the auteur with Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster, screenwriter Daniel Taradash, Frank Sinatra and Deborah Kerr being so perfectly on their game. Likewise, A Man for All Seasons seemed more particularly empowered by the brilliance of screenwriter Robert Bolt and actors Paul Scofield, Roy Kinnear, John Hurt and Robert Shaw than by Zinneman’s solid, somewhat rote direction.

If there is a definitive Zinneman film, it is 1973’s The Day of the Jackal. I agree with David Poland that it was odd — curious — of Emanuel Levy to overlook this film in his Zinneman centennial essay. It is Zinneman’s best because it’s the most taut and well-honed film of his career. Its crisp, dry efficiency not only satisfies from an audience absorption perspective, but it also harmonizes with the arid efficiency of the “Jackal” assassin (Edward Fox). And don’t forget the exquisitely subtle sexiness of Delphine Seyrig as the 40ish woman of property whom Fox meets and beds at that small Southern France hotel.

A shot I took in May 2001 of the exact same beach, located on the east coast of Oahu, where Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr had their famous tryst in From Here to Eternity

Cassel est mort

French actor Jean-Pierre Cassel died three days ago — Thursday, 4.19 — in Paris after a long illness. A statement was issued Friday, the Hollywood Reporter posted Rebecca Leffler‘s story a day after that, and some of us didn’t get around to reading the story until Sunday. The 74 year-old was Vincent Cassel‘s dad. The elder Cassel’s final film, Julian Schnabel‘s The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, will show at the Cannes Film Festival next month.

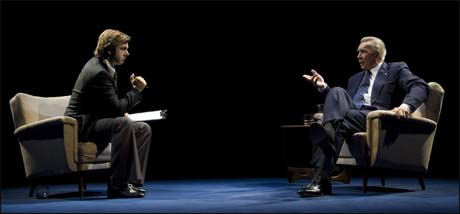

Langella in “Frost/Nixon”

“From the moment he steps onstage, with his hunched walk and lumbering step, Frank Langella has avoided the obvious route of Rich Little-style impersonation of one of the most impersonated figures in history. What he delivers instead is an interpretation that, without imitation, still captures and exaggerates Richard Nixon‘s essential public traits: the buttered-gravel voice, the scowling smile, the joviality that seemed to contain an implicit threat.

“The friend with whom I saw the play asked me afterward if I had noticed how much better Langella’s Nixon impersonation became as the show progressed. Langella’s performance had not changed, but by evening’s end it had eclipsed the familiar photographic image of the real man. Like Helen Mirren‘s understated Elizabeth II in The Queen, this overstated Nixon seems destined forever to blend into and enrich the perceptions of its prototype for anyone who sees it.” — from Ben Brantley‘s review of Frost/Nixon in the 4.23 edition of the N.Y. Times.

And yet Ron Howard, fearful of moviegoers who may be not be innately aroused by Langella’s talent, wants to cast a “name” guy to play Nixon for his movie version, which starts shooting in August. Note to Ron: cast the best man and the hell with marquee value. Make the best film you can and make your next bundle from Angels and Demons. The Frost/Nixon film isn’t going to break records no matter who plays Nixon. Forget the Wild Hogs crowd, the airport-fiction readers, the Da Vinci Code mouth-breathers…forget ’em all.

Hating the Times

L.A. Observed is reporting (and I heard this independently today on my own) that about 70 L.A. Times newsroom jobs are being chopped, which will reduce the editorial staff “from 920 to around 850.” Okay, that’s rough and I’m sorry for those about to be put out to pasture, but if the the paper version of the Los Angeles Times were to disappear tomorrow, a part of me would truly rejoice. I’ve never loathed a newspaper in my life like I hate the Los Angeles Times with those wads and wads of ad supplements falling out all over the place when I read it in a cafe. I love reading a lot of the L.A. Times reporters and columnists, but I hate the paper Times with a passion. Save the forests and make it all cyber. Better yet, bring back the L.A. Herald Examiner.

“Sunshine ” in Europe

Danny Boyle‘s Sunshine (Fox Searchlight, 9.14), a sci-fier about a team of astronauts on a celestial mission to re-ignite a dying sun, won’t open stateside until after Labor Day, but it opened across Europe earlier this month. Some British and European critics have been groaning about the ending, but so far it’s got an above-average 88 % Rotten Tomatoes rating, so it doesn’t sound too problematic. It sounds excellent, in fact, if you leave out the equation of the finale.

I’ve asked the Fox Searchlight folks about seeing Sunshine here in Los Angeles before flying off to France and the Cannes Film Festival on 5.14, but so far they haven’t replied. If my suggestion continues to fall on deaf ears I guess I’ll just take a train to Nice and see it in some paid-ticket multiplex during the festival. (It runs from 5.16 to 5.27, and I’m guessing — hoping — that Sunshine, which opened in France on 4.11, will still be playing five weeks later.) I guess I could also see it somewhere in Italy since I’ll be going there for a few budget-conscious days after Cannes.

On one level it’s pain in the ass to have to chase down a movie this way, but it’ll also be kind of fun.

“Once” is coming

John Carney‘s Once, the most unassuming and wholesomely affecting love story in years that turned into the Big Find at Sundance ’07, opens on May 18th — a little less than four weeks off. Fox Searchlight, which acquired it last February, has launched its own Once website. (The Irish version has a little more pizazz.) Here, in any event, is a fairly decent trailer that catches the mood and tone of the feature.

Glen Hansard, Marketa Irglova in John Carney’s Once

This little Dublin-shot film is about a couple of gifted but struggling musicians — a scruffy, red-bearded troubadour (Glen Hansard, best known for his Irish group The Frames) and a young Czech immigrant mom (pianist and singer Marketa Irglova) — falling for each other by learning, singing and playing each other’s songs. That’s it…the all of it. And it’s more than enough.

Calling Once a “musical” doesn’t quite get it because it’s really its own bird — it’s a tweaking (almost a reinvention) of the form in the vein of Cabaret, A Hard Day’s Night and Dancer in the Dark. On top of which it’s gently soothing in a low-budget, unforced way.. It’s about struggle and want and uncertainty, but with a kind of easy Dublin glide-along attitude that makes it all go down easy.

Once is about spirit, songs and smiles, lots of guitar strumming, a sprinkling of hurt and sadness and disappointment and — this is atypical — no sex, and not even a glorious, Claude Lelouch-style kiss-and-hug at the finale. But it works at the end — it feels whole, together, self-levitated.

Trust me — there isn’t a woman or a soulful guy out there who won’t respond to Once if they can be persuaded to just watch it. The trick, obviously, is to make that happen, and I admit there may be some resistance. Initially. But once people sit back and let it in (and they’d have to be made of second-rate styrofoam for that not to happen), the game will be more or less won. Settled, I mean.

Carney, Hansard and Irglova are starting a 15-market p.r. tour from April 30 to May 18. They’re in Manhattan on May 1st and Los Angeles on May 15th. In each city Fox will be holding special promotional showings followed by a performance and q & a in each market, which is the template that worked so well at each one of the Sundance screenings last January.