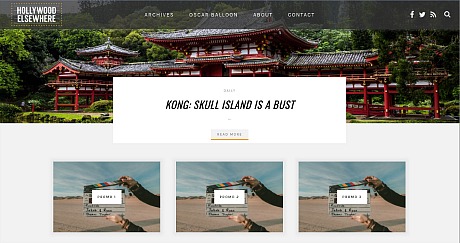

A re-design is underway of Hollywood Elsewhere. The idea is to make it look and feel more 21st Century (the design mentality of the current site is 13 years old — it actually looks like it could have been designed in the late ’90s), and to load faster and be more ad-friendly and so on.

I’m down with this, but my concern all along has been to make sure the new site conveys a distinct “things haven’t changed that much” feeling — an assurance that HE’s identity and attitude is alive, intact and continuing within this new design. The new site should say “sure, this look significantly different in some ways, but it’s still very much the site that I’ve built, poured my heart into and self-branded over the last 12 and 1/2 years.”

A fresh, here-and-now design is essential but, as I’ve told the designers, Hollywood Elsewhere is nothing if not about my personal brand — my views, attitude, personality, passion, errors, shortcomings, gushings, travels, tenacity, aspect ratios, experience, arguments, prejudices…all of it. The new design needs to recognize this and embrace continuity.

Please look at the test site as it now stands. Keep in mind that it’s a very early stab. I’m not hugely unhappy with the mobile version but the classic HE identity, I feel, has been all but erased. The initial idea was to take a generic uptown design, which looks like a Paris fashion magazine and which I thought was half-decent, and merge it with HE’s style and personality.

The small, almost-postage-stamp-sized HOLLYWOOD ELSEWHERE logo in the top left says it all. The designers of this test site seem to be interested in obscuring if not erasing the entire identity of Hollywood Elsewhere, which has been running since August ’04. (HE has actually been punching it for 18 and 1/2 years if you count my Mr. Showbiz, Reel.com and Movie Poop Shoot incarnations between October ’98 and July of ’04.)

It’s a mistake, for starters, to jettison the HE Hollywood sign logo, to not use my photo for identity purposes, to not use the same copy and headline fonts. Continuity is vital.

Read more