Congrats all around but especially to the Best Director-nominated Chloe Zhao and Emerald Fennell and the ten-nominations-fortified Mank, not to mention surprise Best Director nominee Thomas Vinterberg (Another Round) and the Best Supporting Actor nom handed to Judas and the Black Messiah‘s LaKeith Stanfield (yes!)…and to HE fave Riz Ahmed (Sound of Metal) for Best Actor. And to the concept of diversity in general. Definitely a spread-it-around year.

I decided at the last minute that I couldn’t arise any earlier than 4:50 am and even that was painful after crashing at 1:05 am…plus daylight savings time kicked in early this morning and thereby subtracted an hour’s sleep…I’ll finish when I finish…this is not a track and field competition.

I somehow hadn’t expected David Fincher‘s Mank to emerge as 2021’s double-digit nomination king, but congrats all the same. And Mank‘s Amanda Seyfried, whose prospects were looking a bit shaky, came through with a Best Supporting Actress nom! And cheers also to Netflix for landing 35 nominations in all.

Odd that Mank began with Jack Fincher‘s mid ’90s script, and yet that script, augmented by the great Eric Roth as well as Jack’s son David, wasn’t Oscar-nominated.

Special congrats to Sound of Metal‘s Paul Raci for landing a richly deserved Best Supporting Actor nom. I was worried about his prospects all along as awards-giving-group after awards-giving group kept blowing him off….thank goodness!

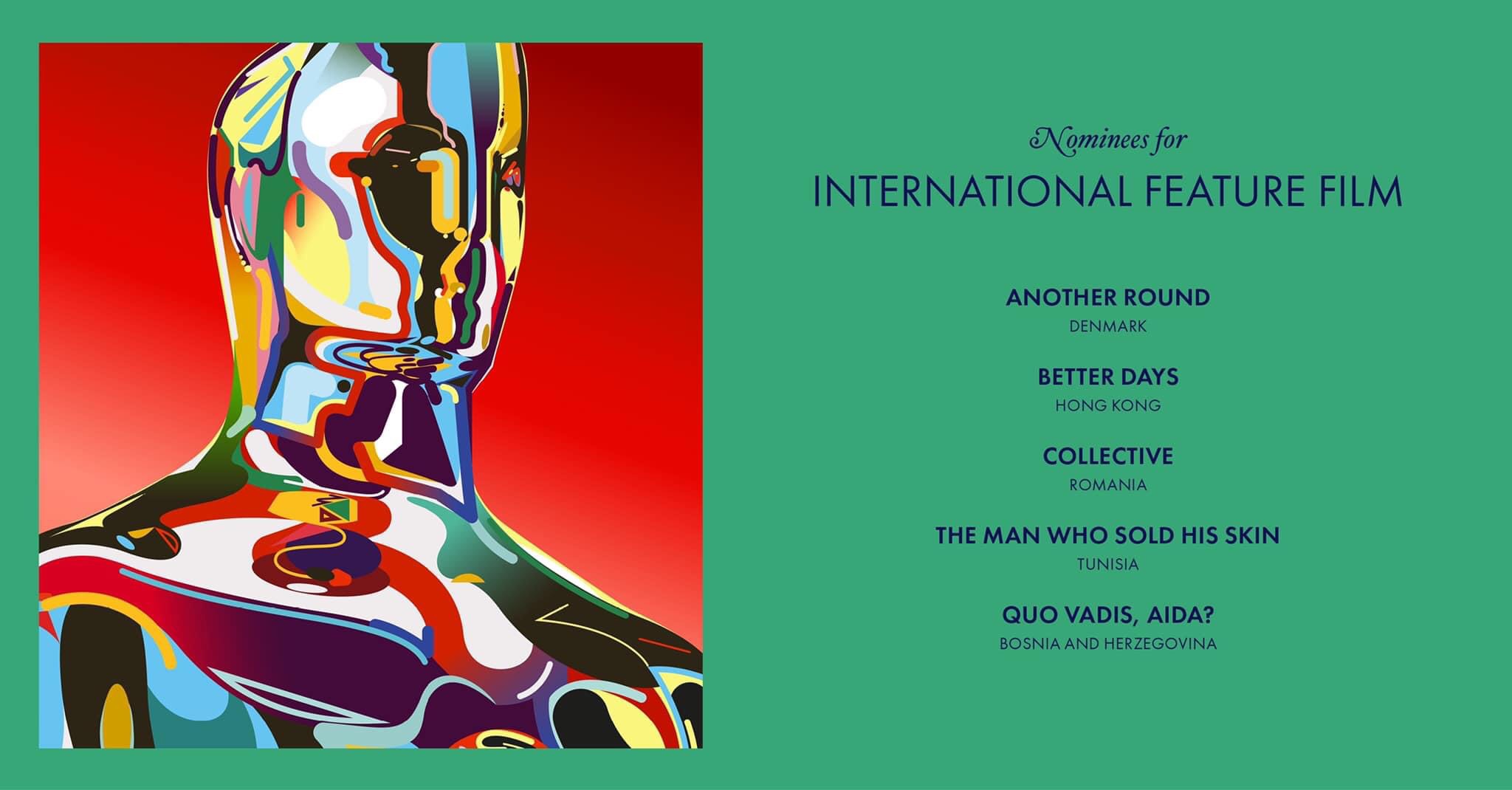

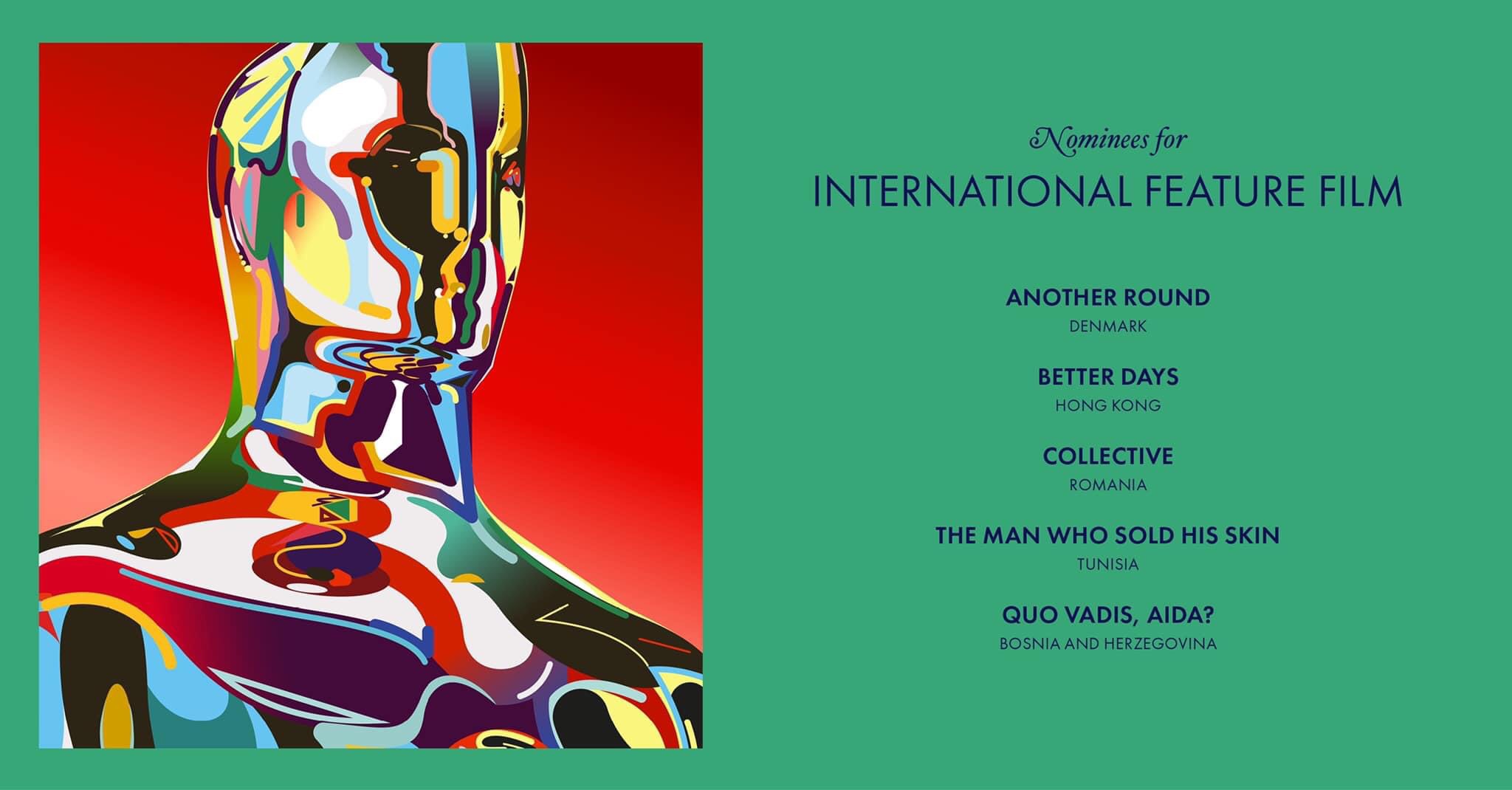

Shame on the Best International feature nominating team for blowing off Andrei Konchalovsky‘s Dear Comrades, by far my preference among the contenders in this category.

Congrats to the five int’l nominees all the same: Another Round (Denmark), Better Days (Hong Kong), Collective (Romania…highly approved!), The Man Who Sold His Skin (Tunisia) and Quo Vadis, Aida? (Bosnia-Herzegovina…harrowing genocide film, only just saw it a week or so ago).

Remember the good old days when the New York Film Critics Circle was regarded as an occasionally predictive body as far as major Oscars noms were concerned? Before they moved lock, stock and barrel to Planet Woke? Their instincts proved prophetic as far as Best Director nominee Chloe Zhao and Best Supporting Actress nominee Maria Bakalova are concerned, but has anyone seen First Cow around lately? The NYFCC also went with Da 5 Bloods‘ Delroy Lindo for Best Actor and Never Rarely Sometimes Always‘ Sidney Flannigan for Best Actress.

__________________________________

Best Picture: The Father, Judas and the Black Messiah, Mank, Minari, Nomadland, Promising Young Woman, Sound of Metal, The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Best Picture Blowoffs: Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Regina King‘s One Night in Miami (respectful salute but it was never in the cards), Paul Greengrass‘s News of the World…which others?

Best Director: For the first time in history two women were among the five nominees — Nomadland‘s Chloe Zhao and Promising Young Woman‘s Emerald Fennell. Special congrats also to Thomas Vinterberg for Another Round (big surprise + high approval for an effort I didn’t get around to seeing until a week ago because I’m not a big fan of films about boozing). Plus Mank‘s David Fincher and Minari‘s Lee Isaac Chung.

Best Director Blowoffs: Chicago 7‘s Aaron Sorkin, The Father‘s Florian Zeller, Sound of Metal‘s Daris Marder, One Night in Miami‘s Regina King. With only five slots, a few had to fall by the wayside…sorry, due respect. The international Academy voter factor led to Vinterberg’s nomination, for sure.

Best Actress in a Leading Role: The United States vs. Billie Holiday‘s Andra Day (full respect for single best element in Lee Daniels‘ film), Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom‘s Viola Davis (steamroll bluster — nom expected all along, won’t win), Pieces of a Woman‘s Vanessa Kirby (rounding out the pack), Nomadland‘s Frances McDormand (fritos!) and expected winner Carey Mulligan for Promising Young Woman.

Best Actress Blowoffs: None to speak of. Despite what Deadline‘s Pete Hammond projected a while back, The Life Ahead‘s Sophia Loren was never really in the running. Well, she was but without any noticable steamroll effect, at least not as far as HE’s insect antennae vibrations were concerned.

Best Actor in a Leading Role: Sound of Metal‘s Riz Ahmed (yes!), Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom‘s Chadwick Boseman, The Father‘s Anthony Hopkins (certainly!), Mank‘s Gary Oldman, Minari‘s Steven Yeun.

Best Actor Blowoffs: Da 5 Bloods‘ Delroy Lindo, who might’ve had a chance if costar Boseman hadn’t tragically passed last August. The performance by The Mauritanian‘s Tahar Rahim was too quiet and modest to land a nomination. If HE was an emperor-dictator I would have given a nom to The Way Back‘s Ben Affleck — his boozy basketball coach has authority and conviction.

Best Actress in a Supporting Role: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm‘s Maria Bakalova; Hillbilly Elegy‘s Glenn Close (HE predicted eons ago that she would be nominated and sure enough she bulldozed her way in, much to the chagrin of many elite critics) , The Father‘s Olivia Colman, Mank‘s Amanda Seyfried and Minari‘s Yuh-Jung Youn (funny, fire-starting grandma).

Best Supporting Actress Blowoffs: The Mauritanian‘s Jodie Foster (sorry, good performance, somebody had to be cut).

Best Actor in a Supporting Role: The Trial of the Chicago 7‘s Sacha Baron Cohen (yes!), Judas and the Black Messiah‘s Daniel Kaluuya (not as good as Stanfield), One Night in Miami‘s Leslie Odom, Jr.; Sound of Metal‘s Paul Raci (yes!) and Judas and the Black Messiah‘s LaKeith Stanfield (yes!). Who will win? Fascinating competish.

Best Original Screenplay: Judas and the Black Messiah (Will Berson, Shaka King, Keith Lucas & Kenny Lucas…go, Clayton Davis!); Minari (Lee Isaac Chung); Promising Young Woman (Emerald Fennell); Sound of Metal (Derek Cianfrance, Abraham Marder & Darius Marder); The Trial of the Chicago 7 (Aaron Sorkin). I’m presuming Sorkin will win this one as a make-up for not being nominated for Best Director.

Best Adapted Screenplay: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm (Peter Baynham, Sacha Baron Cohen, Jena Friedman, Anthony Hines, Lee Kern, Dan Mazer, Erica Rivinoja & Dan Swimer); The Father (Christopher Hampton & Florian Zeller); Nomadland (Chloé Zhao); One Night in Miami (Kemp Powers); The White Tiger (Ramin Bahrani). HE predicts The Father or Nomadland to win.

Best Cinematography: Judas and the Black Messiah, Mank, News of the World, Nomadland and The Trial of the Chicago 7. The likeliest winner is…?

Best Documentary Feature: Collective, Crip Camp, The Mole Agent, My Octopus Teacher, Time. HE supports either Collective or Time.

Best Animated Feature Film: Onward, Over the Moon, A Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon, Soul, Wolfwalkers. HE sez “no” to Soul.

And all the others…

Best Costume Design: Emma, Mank, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Mulan, Pinocchio

Best Original Score: Da 5 Bloods, Mank, Minari, News of the World, Soul.

Best Live-Action Short Film: Feeling Through, The Letter Room, The Present, Two Distant Strangers, White Eye.

Best Animated Short Film: Burrow, Genius Loci, If Anything Happens I Love You, Opera, Yes–People

Best Documentary Short Subject: Colette, A Concerto Is a Conversation, Do Not Split, Hunger Ward, A Love Song for Latasha.

Best Sound: Greyhound, Mank, News of the World, Sound of Metal, Soul.

Best Production Design: The Father, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Mank, News of the World, Tenet.

Best Film Editing: The Father, Nomadland, Promising Young Woman, Sound of Metal, The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Best Visual Effects: Love and Monsters, The Midnight Sky, Mulan, The One and Only Ivan, Tenet.

Best Makeup and Hairstyling: Emma, Hillbilly Elegy, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Mank, Pinocchio.

Best Original Song: “Husavik” from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga, “Fight For You” from Judas and the Black Messiah, “lo Sì (Seen)” from The Life Ahead (La Vita Davanti a Se); “Speak Now” from One Night in Miami; “Hear My Voice” from The Trial of the Chicago 7. HE supports Diane Warren‘s “lo Sì”.