In the comment thread for yesterday’s “Beto Needs To Get On The Stick” piece, a dude named Otto wrote that Beto O’Rourke‘s seeming hesitancy (i.e., thinking things over during a solo road trip) indicates that the former El Paso Congressperson “will be the perfect VP pick for someone like Biden. [Accepting this status] would show (1) authenticity, (2) modesty (I’m not yet ready) (3) lack of the super-ego that drives most narcissist who want to be President and (4) wisdom in understanding that he has more to learn about national/international affairs.”

Persuasive HE response: “A malignant sociopath is in the White House right now, and you’re quibbling over fractions, resumes and modes of experience? Remember all the crap in ’07 and ’08 about how Barack Obama, a wet-behind-the-ears junior senator from Illinois, was too young, too naive, not seasoned enough for the Presidency? Beto (currently 46) is a year older than Obama was when he announced in ’07, and he knows his way around. But the bottom line is that THERE’S NO TRAINING ACADEMY FOR THE PRESIDENCY. You just jump into the pool and swim as best you can.

“Do you think JFK was supremely qualified when he took over? Do you think Clinton was? Do you think Dubya was wonderfully qualified and super-knowledgable? He was a brash ignoramus who leaned on his father’s friends. Do you think Abraham Lincoln of the Illinois legislature was exquisitely trained and ready to run things when he moved into the White House in March 1861? You either live up to the demands of the office or you don’t.

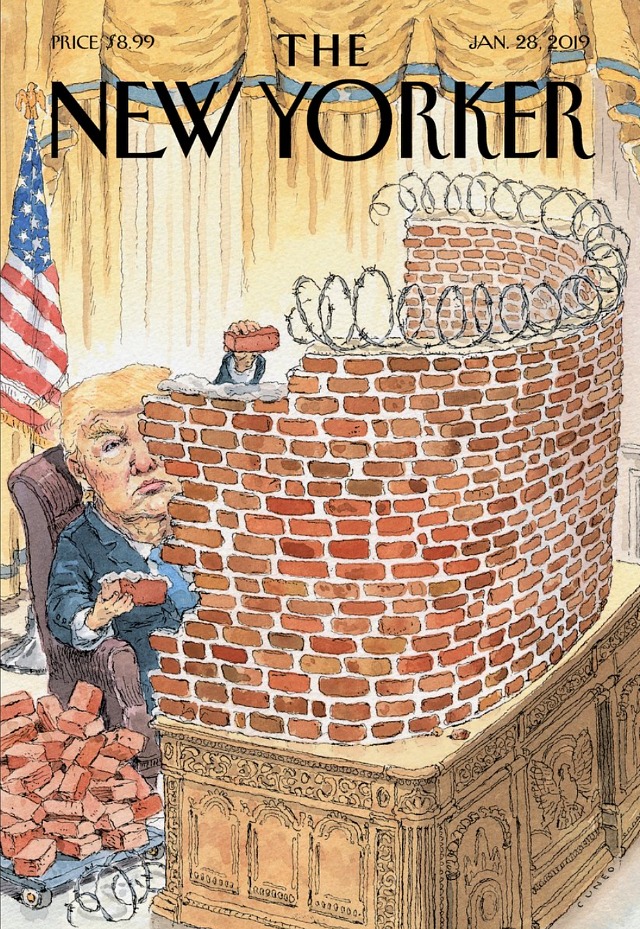

“And right now an animal who’s polluting the Oval Office is running the show. A bloated pusbag sociopath and unregenerate liar…a guy who’s brought into Washington the worst pirates and grifters since the Harding administration and who believes that climate change is a hoax…the head of a lying, grifting crime family is running the country. And the only name of the game is “getting him out of the Oval office by January 2021 if not before.” That means two things: (a) impeachment by the House and (b) nominating a younger X-factor charisma candidate (who’s incidentally taller than Trump) to oppose him. Period. Not a shrill SJW libtard but someone with a moderate human touch.

I followed up with a comment about Biden: “Uncle Joe is a good, likable guy with a settled vibe and a history of practical, sensible liberalism. Obviously superior to Trump in every way imaginable. And a human being. But he’s too old (76 as we speak, 78 during the ’20 campaign), too yesteryear, too gaffe-prone, too withered. The Democratic 2020 candidate has to be about the future. I’m sorry, but the culture is demanding the absence of Oval Office neck wattles, at least for the foreseeable future.”

Commenter “Jeff”: “Democrats don’t win with old vetted ‘sure things’. Hillary, Kerry and Gore all felt like battle-tested sure things. The last three Dems elected were on their 40s or early 50s. If you acknowledge that LBJ really won Kennedy’s second term, then it’s four in a row. Hell, even FDR was barely 50 when he was first elected.”

HE correction: FDR was just shy of 51 when he was elected in November 1932. LBJ was 56 when he beat Barry Goldwater in November ’64. The Democrats really, really don’t want a candidate in his or her late 70s running for the White House.