Yesterday Brian DePalma and Magnolia’s Eammon Bowles debated the issue of certain grisly photographs of Iraq casualties having been removed from the end of DePalma’s Redacted due to concerns about legal vulnerability. The discussion happened at a N.Y. Film Festival press conference held yesterday afternoon. Movie City Indie’s Ray Pride has posted good information about this, including a statement from Bowles.

JFK, George Smathers, Oscar predicting

This old JFK anecdote about bad advice he got for years from Sen. George Smathers reminds me that in politics as well as Oscar forecasting, there are some predictions you automatically disregard.

Four adult films competing

Three serious adult dramas are opening against each other wide on 10.19 — Ben Affleck‘s Gone Baby Gone, Gavin Hood‘s Rendition, and Susanne Bier‘s Things We Lost in the Fire. And a fourth — Terry George‘s Reservation Road — is opening limited the same day also.

Four films fighting over the same over-25 audience is a form of public suicide. Bier’s film is easily the best of the bunch, but even with this advantage you have to figure at least two or three of these films will take a hit.

And I mean especially with the strong likelihood that the under-25 empties will make 30 Days of Night, a Josh Hartnett-starring horror film, the weekend’s biggest opener.

Punch-up problems

A well-employed screenwriter wrote earlier today to point out an angle in the stories about the likely WGA strike that no one’s mentioned. “I’ve been making most of my living over the last few years as a script doctor / punch-up person,” he wrote, “and many of the movies now hurriedly wrapping or being rushed into production will not be able to handle the usual studio-mandated reshoots that inevitably occur after test screenings if a strike is on.” The punch-up guys will have their hands tied, and producers will be caught between a rock and a hard place.

Spielberg geek luncheon

Partly as a result of a certain online journalist making a call last week to Paramount Studios which led to the “sting” arrest of Roderick Davis, the 37 year-old Cerritos resident who tried to peddle hundreds of stolen photos from the shoot of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull for $2000 bucks, director Steven Spielberg hosted a small “thank you” lunch and set visit today for a small group of fanboy web journalists at Universal studios.

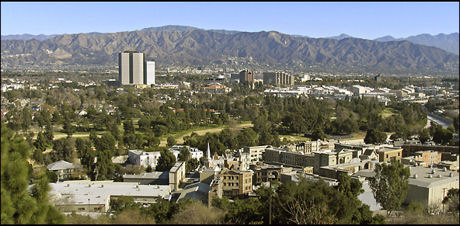

Universal Studios lot (foreground)

The group included CHUD’s Devin Faraci, “Quint” from Ain’t It Cool and, I’ve been told, a rep from Slashfilm and Dark Horizons. I’m not sure if Latino Review‘s Kellvin Chavez (who flew out from NYC for the meeting) and IESB.net’s Robert Sanchez attended, but I’m told they were invited at one point.

Spielberg, currently directing Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, was presumably looking to bond with these leading web journos and foster allegiance in case another stolen-photo incident occurs down the road.

The luncheon/set visit was almost cancelled yesterday because “too many people found out about it,” I was told by two sources. The invited parties were “supposed to keep it to themselves…they shot themselves in the foot.” A guy involved in the back and forth told me yesterday that “some people have gotten their butts very hurt over [this] whole thing, and Paramount is dealing with sites complaining about not getting invites.”

Here’s Quint’s story on AICN about the meeting. a story about Transformers 2 that was sourced directly to Spielberg by way of Devin Faraci was posted a little while ago.

I wrote yesterday about the above-described online journalist who made the call, etc., but I took the story down because the journalist called to express concern that Davis’s accomplice (or accomplices) might possibly take revenge for providing information that led to his arrest. I’ve never written about a criminal matter before, but I decided yesterday that if there was a one-in-a-hundred chance that some kind of payback might be visited on this journalist or his family (a scenario out of a bad TV episode) I didn’t want to be involved.

L.A.’s Standard Hotel

I had called this journalist last weekend to encourage him to write a detailed piece about the episode and maybe even sell it to some large, well-paying print publication. It’s got everything, after all — a threat to the profile of a much-awaited film, a big-name director (Steven Spielberg) and big movie stars (Harrison Ford, Cate Blanchett, Shia Lebouf), stolen property, and a secret sting operation arranged in collusion with authorities.

The guy was contacted seven or eight days ago by Davis with an offer to sell the stolen Indy 4 photos or a lousy two grand. A couple of sample photos were sent to prove that Davis had the goods. The online journalist quickly notified Paramount publicity about the offer, they called the L.A. Sheriff’s office and a “sting” meeting was arranged to to happen last Tuesday afternoon at the L.A.’s Standard Hotel. (Note: I was told by a Paramount source that the FBI was involved.)

A story about the theft and arrest ran on IESB.net last Tuesday, saying that “the thief was apprehended by LAPD and the FBI” even though, according to L.A. Times reporter Richard Winton, it was an L.A. Sheriffs operation.

The story wrote that the sting happened “with the help of a member of the online press [who] had been offered the stolen property. Sources tell us that an undercover sting operation was set in motion late last night,” the story reported, “with the help of the unnamed member of the online press.”

“A meeting between the alleged thief and the unnamed online reporter was set up for 4:00 pm at the Standard Hotel on Sunset Blvd. The sting went as planned and the arrest was made. The IESB has been told that the alleged thief was in possession of the stolen property.”

A 10.4 L.A. Times story about the bust by Winton and Andrew Blankstein said that lawmen “e-mailed the suspect, saying they were interested in purchasing the photos,” alrhough it made no mention of Sanchez. The feds rented a room, Davis showed up and tried to talk business…surprise, busted, cuffed.

Both Winton and the online reporter told me they’d beebn told that Davis had an accomplice or accomplices, and that this said parties are on the loose.

More interesting details, I’m sure, have yet to be revealed. I just hope it gets written up thoroughly some day, and written well.

Benny on “Oprah”

It doesn’t feel right somehow when guys like Benicio del Toro go on Oprah and do the old turn-on-your-love-light routine. He did it for Susanne Bier‘s Things We Lost in the Fire, which Paramount is opening on 10.19, but the guy in this photo and the guy he plays in the film are so different it’s weird. His real-life personality is another planet also. I’ve never seen Benicio smile like that ever.

“Jesse” dissed in Pheonix

Pheonix-based entertainment journalist Henry Cabot Beck wrote earlier today to report that “here in Arizona it was announced yesterday that despite The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford opening this Friday in Phoenix, it’s been decided at the last minute not to screen it for critics.

“It was touch-and-go yesterday for about an hour with the talk being that they might screen it tonight (Tuesday) with a one-day notice,” he adds. “Depending on how this shakes out, this could mean that Jesse James has become the most lauded, worst-treated movie of the year.

“Everybody’s split on the picture, but some feel that Andrew Dominik‘s film is one of the best of the year. I fall a bit over into that camp. A Brad Pitt picture with some Oscar buzz, a couple of amazing performances — even if you don’t like the movie overall — and they’re treating it like a one-weekend horror turd.”

“Fred Claus”

I’ve been trying to avoid dealing with Fred Claus (Warner Bros., 11.9), an obviously broad and garishly commercial family comedy starring Vince Vaughan, Paul Giamatti and Rachel Weisz, but it’s been made, it opens a month from now, and we may as well stand up like adults and face it. Every November somebody releases a right-down-the- middle family holiday film, and this seems to be a semi-misanthropic 2007 version. An upbeat Bad Santa without the booze and set in a Polar Express-ian Santa’s village?

I was with the trailer until those ninja elves turned up. That was it. Check-out time. I’ll be out in the lobby.

The story is an appropriately snide and smart-ass spiritual redemption tale. Fred Claus (Vaughn) is the embittered brother of Nicholas “Santa” Claus (Giamatti). A repo man sent to the slammer for stealing, Fred is bailed out by Nick on the condition that he return home to the North Pole and enter the family business. And you know the rest.

The trailer strongly suggests this was a straight paycheck job for everyone concerned — Vaughan, Giamatti, Weisz, director David Dobkin (The Wedding Crashers), producer Joel Silver and senior costars Kathy Bates, Kevin Spacey and Miranda Richardson.

Sometimes you just have to suck it in, hold your nose, make the movie and cash the check. And the family audience is happy because they have no taste as a rule and will scarf down anything you put in front of them.

A friend saw a preview and had nice things to say about Giamatti’s Santa Claus (“wonderful…exuded great warmth”) and applauded Weisz for making her part play much better than written. She feels that the script by Dan Fogelman (Cars) is…uhm, how should I put this? I don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings. Okay, the word she used was “terrible.” She also feels that Fred Claus belongs more or less in the same category as Ilya Salkind‘s Santa Claus (’85), but that’s a horrible thing to say. I’m sure she didn’t mean it.

Her final thought: “I thought I’d be seeing another Elf and what I got was something that made those Tim Allen Santa Clause movies seem like Kubrick.” That’s a little blunt. Too abrupt and dismissive. Something tells me this may turn out to be half-tolerable. I can’t accept that Vaughn, who co-produced, would star in something as bad as she’s described here. There must be more to it….no?

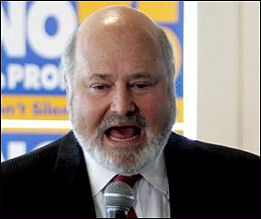

Reiner’s Hillary spot

Two random thoughts about Rob Reiner‘s somewhat messy but passionate online ad for Hillary Clinton, which was sent around today.

One, Reiner has cast himself in the spot, and seems very much of an amusingly hyper, judgmental live-wire type. (More so than he’s ever seemed to me during junket round tables.) So much so that you can’t help but wonder, “How could such a hyper, judgmental live-wire type make such cautious, edgeless movies like Rumor Has it, The Story of Us, Alex & Emma , North and Ghosts fo Mississippi for the last ten to twelve years?” Reiner doesn’t seem to have put himself into these films. At all.

And two, the central statement in Reiner’s spot comes when he advises a Hillary volunteer to tell people she’s calling that she’s “100% convinced that she’s the only candidate who can actually change things.” This, of course, is code for “she’s the only Democratic candidate likely to win” but is she? And given Clinton’s polarizing profile and temperamental nature, is it all that likely she’ll actually change things, or will she mainly agitate and enrage?

Hilary’s inevitability?

Last Thursday’s Washington Post poll convinced a lot of people that Hilary Clinton is probably going to win against Rudy Giuliani. The Post‘s hypothetical matchup between Clinton and Giuliani showed Hilary leading Rudy 51 percent to 43 percent. A legislator was recently quoted by Peggy Noonan as saying that “it’s all over but the voting.”

The problem for me (for many lefties) is that Hilary Clinton will almost certainly polarize more ferociously and draw more hate (and God knows what else) than Barack Obama would. Hilary might win, but Obama would be a better candidate, a better uniter and a better consensus-builder. We all know that what a rancid, butt-ugly general campaign it will likely be next summer and fall if it comes down to Hilary vs. Rudy. And I shudder to think what the right-wing crazies will throw at Clinton once she (presumably) lands the nomination.

Two worrisome thoughts, one voiced by elrapierwit on Kevin Drum‘s Washington Monthly blog (i.e. “Political Animal”) and a reader quoted on Andrew Sullivan‘s Atlantic Monthly blog.

The Sullivan reader addresses the Obama-regarded-by-righties factor: “Those who say the right will cook up a narrative about Obama just as poisonous and effective as the right’s Hillary narrative are wrong. Poisonous, yes; effective, no.

“I just had dinner with my father, and for several years I’ve avoided talking politics with him; he’s a highly intelligent man but he became a neocon 30 years ago and then, to my horror, a regular Limbaugh listener.

“He belittles every candidate I’ve liked by spitting out the Limbaugh-dictated putdown or some close variant thereof. Anyways, we were forced to talk politics because a friend noticed us and came up to our table and mentioned I am an Obama supporter. I was expecting some anti-Obama venom from my father, but it did not happen.

Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Rudolph Giuliani

“Predictably, my father’s going to vote for Giuliani. But he agreed with that Peggy Noonan column from a few days ago saying that Obama is genuine and thoughtful, and he thinks he’s the only Democrat who can avoid being effectively savaged by Limbaugh and the talk-radio world because he thinks their insults don’t stick to Obama the way they stick to Hillary.

“Unscientific, I admit. But when you realize what a hold Limbaugh has over his dittoheads, it’s worth noting that they agree with every word he says about Hillary but they can’t help liking Obama. The reason, I think, is simple. There is an element of truth in the talk radio right’s portrayal of Hillary as a smug, self-righteous, phoney. Liberals and Hillary admirers hate to hear that, but it’s true — an element of truth obscured by a whole mountain of b.s.

“There is not, however, even a grain of truth in the Hannity/Limbaugh Obama slurs to date. The Obama/Madrassah slur won’t stick because it is not only not true; it’s not even ‘truthy.’ Obama is obviously a humanist in the best sense of that word and thus the polar opposite of a Madrassa fanatic. Nor will the slur stick about Obama being a champion of Afrocentric black power because he attends a church whose minister has those leanings.

“To the contrary, it seems extremely likely to me that if Obama steals the nomination from Hillary, a huge cross-section of the country will fall in love with him as a person, either right then and there or after his acceptance speech. That cross section will include conservatives who won’t vote for him but will still like him as a human being. Even those who think this scenario is not highly probable would acknowledge it is more than possible.

“And if they are being honest with themselves, they have to admit that It is simply not possible for Hillary to generate that kind of reaction. She may well win, but even if she does, most of the 49 or 48% who vote for her opponent will walk into the voting booth detesting her and will promptly come to detest her even more after her triumphal inaugural speech and ceremonies. If Obama can pull off a victory, there will be an entirely different vibe.”

El Rapier‘s comment: “[The] assertion that Hillary [has been] ‘made polarizing’ by the right is completely specious. No one can make an individual polarizing. Hillary is polarizing because she confuses power with leadership and is unable to create and build consensus within a diverse group of thinkers. That is why she is polarizing. She tries to drive issues without building a winning coalition.

“All you have to do is look at how she managed the proposed Clinton healthcare plan in the ’90s. It was a ‘my way or no way’ because she thought she had the power as First Lady to drive the agenda on her own terms without taking into consideration what the needs of others were.

“No one told Hillary to divide 500 people into 34 committees and demand they not say anything outside of the meeting nor take notes in the meeting. The right did not make her do that.

“No one told Hillary to take the fight to the Supreme Court on her terms for secrecy. Hillary conceived all of that on her own and she believed she had the power to force her ideas and agenda on others. The right did not make her do that. She simply lacked leadership and the ability to persuade others to the validity of her proposals.

“Hillary is far more polarizing than any other politician during her political era. She in fact is going to be a reason for all the old partisian bickering and long standing grudges to come back to the fore meaning nothing will be accomplished.

“Hillary has told people during her campaign for the Presidency that those not on board with her now will pay when she is the nominee. A hallmark trait of a vengeful politician not a leader.

“So nothing has changed. She is a fighter and a brawler. She is not a leader.”

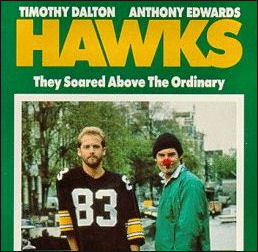

“Hawks” = “”Bucket List”?

Conscientious reviewers who plan on reviewing The Bucket List should probably try to hunt down a VHS tape of a British-produced 1988 film called Hawks. It’s about two terminally ill patients (Anthony Edwards, Timothy Dalton) in a grim English hospital yearn who plot an escape for one last wild time, and who hook up with two English women (Janet McTeer, Camille Coduri) on their way to the brothels of Amsterdam . At least for curiosity or perspective’s sake.

An Amazon enthusiast has called it “a rare gem that balances humor and pathos and avoids maudlin sentimentality in handling a very serious issue. The chemistry between Dalton’s bitter but lively intellectual and Edwards’s cocky but vulnerable jock propels the film to great heights. And while they keep the humor coming, neither screenwriter Roy Clarke nor director Robert Ellis Miller ever forget the direction that Decker and Bancroft’s lives will ultimately take.”

“Bucket List” trailer

This high-def trailer for Robert Reiner‘s The Bucket List (Warner Bros., 12.25) is one of those trailers that appears to tell you every major plot beat in the film, start to finish. It even appears to divulge which character dies early and which one survives so he can hug his estranged granddaughter. It seems so on-the nose, so Reinerish…I don’t know.

I haven’t read Justin Zackham‘s script (has anyone?), but I’m seeing this invisible subtitle that says, “Okay, here’s the whole movie including the ending. Now, would would you like to see the feature-length version?

Bucket List thoughts (i.e., things to do before you’re dead) glimpsed on a yellow note pad: 1. Witness something truly majestic. 2. Help a complete stranger. 3. Laugh until I cry. 4. Drive a Shelby Mustang. 5. Kiss the most beautiful [remainder of sentence obscured, but presumably it doesn’t say “kiss the most beautiful dog”]. 6. Get a tattoo. (What’s so spiritual and life-affirming about getting a tattoo?)

Activities glimpsed: Jack Nicholson and Morgan Freeman sky-diving (rendered, I presume, with very believable CGI — very nice work), driving the Shelby Mustangs on a race track, sitting atop the Egyptian pyramids, riding a chopper along the Great Wall of China, visiting a seaside hill town in Italy.

The question should be, what would two terminally-ill guys without much money do if they wanted to kiss the sky before dying? That notion has no place in Reiner’s head. Not on a Warner Bros. budget, at least.

Baldness sidebar: After Nicholson appeared on the Oscar telecast last February with his head shaved, it was understood this was due to his character, a rich obnoxious blowhard who grows a heart when faced with his own mortality, undergoing chemotherapy, and that he’d be doing the egg-bald thing throughout the film.

Except the trailer shows that his hair is shaved off in the film (presumably in preparation for brain surgery) but he doesn’t spend the whole film bald, as he’s shown in every scene but one with his sparse thatch intact.