I saw Dominik Moll‘s The Night of the 12th (Film Movement, 5.19) last night at the delightful New Plaza Cinema (35 W. 67th Street, NYC) — a modest but dedicated arthouse for discerning adults. I was so happy to be sitting in the front row of a theatre where I belonged, a Film Forum- or Thalia-like shoebox…whistle-clean, air-conditioned comfort, ample leg room and surrounded by older folks not eating popcorn.

The film is a mostly fascinating, vaguely haunting, Zodiac-like police investigation drama that won six Cesar awards (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adaptation, Best Supporting Actor, Most Promising Actor, Best Sound) last February.

It’s a shame, I feel, that almost no one in this country is going to pay the slightest amount of attention. It’ll eventually stream, of course, but it probably won’t attract anyone outside Francophiles and the fans of grim police procedurals, mainly because it doesn’t do the thing that most people want from such films, which is the third-act delivery of some form of justice or at least clarity.

Night is about a cold case — a prolonged and frustrating and ultimately fruitless investigation of a savage murder of a young girl in Grenoble, France…frustrating and fruitless unless you tune into the film’s forlorn wavelength, which is about something more than just whodunit.

It’s based on a fact-based 2020 novel by Pauline Guéna.

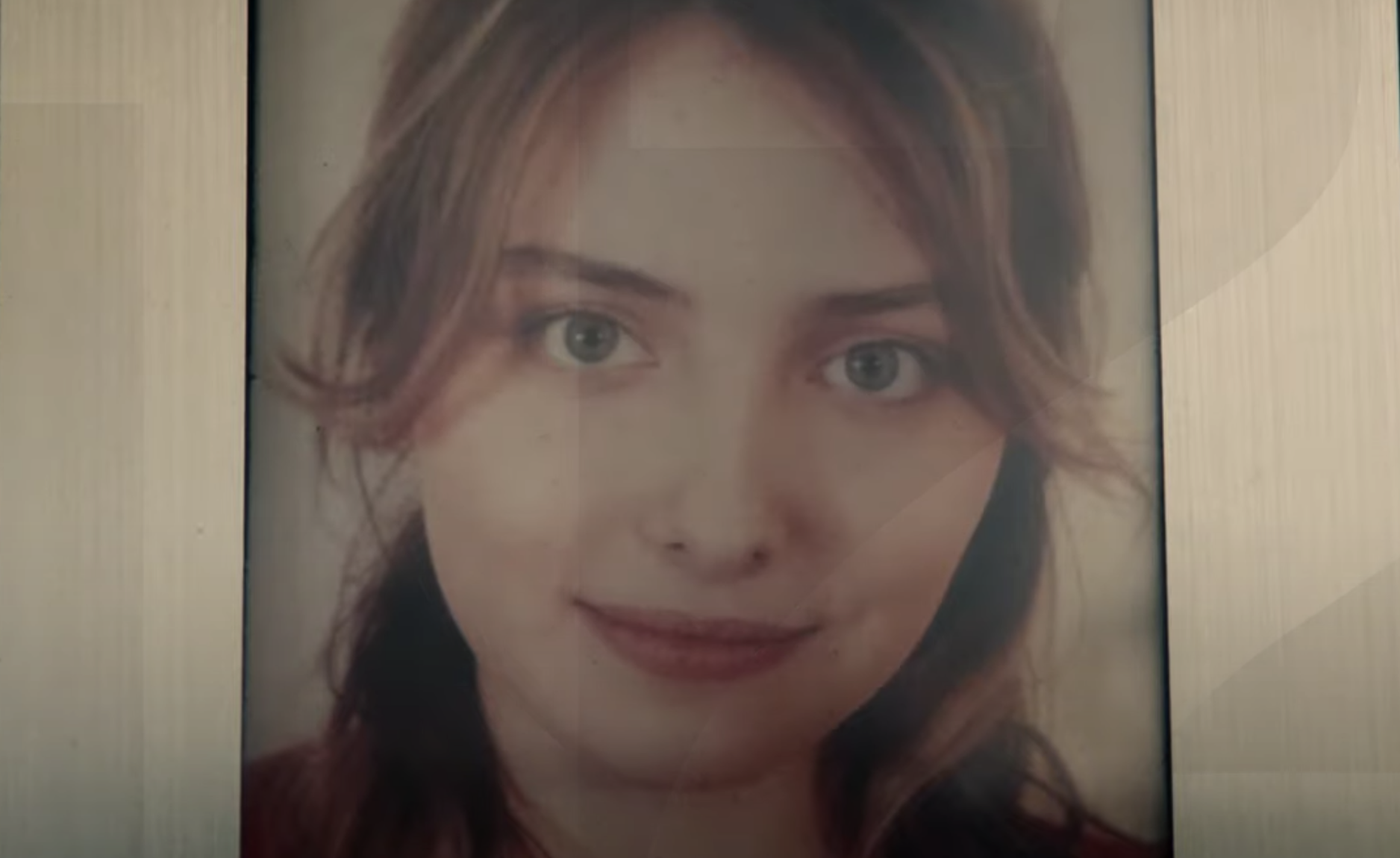

The victim is Clara (Lulu Cotton-Frapier), a beautiful, blonde-haired 21 year-old student who lives with her parents. After leaving a party in the wee hours and while walking down a moonlit street, she’s approached by a hooded wacko and set aflame — a horrible sight. The film is about two Grenoble detectives, played by Yohan (Bastien Bouillon) and Marceau (Bouli Lanners), as they interview and investigate several potential killers whom the casually promiscuous Clara had been sexual with at different times.

All of these guys are scumbags of one sort of another, and you start to wonder why she didn’t have at least one male friend or lover who wasn’t an animal. The digging goes on and on, but no paydirt.

The essence of The Night of the 12th is militant feminism mixed with intense grief. It’s saying there’s a subset of appallingly callous young men out there today…aloof, cruel, thoughtless dogs who sniff and mount out of raw instinct, and this, boiled down, is what killed poor Clara.

Last month in Cannes Martin Scorsese said that Killers of the Flower Moon wasn’t a whodunit but “a who-didn’t-do-it?”

Same with Night — Yohan concludes at the end that “all men” killed Clara, and so among the Cesar voters and the guilty-feeling industry fellows who felt an allegiance with their feminist collaborators… this water-table sentiment, an adjunct of the Roman Polanski-hating faction, is presumably what led to The Night of the 12th‘s big sweep.

By this measure Night isn’t about a “cold case” — it’s a kind of hot-flush case that points in all kinds of directions to all kinds of potential young-feral-dog killers…a limitless (in a sense) roster of bad guys.

In order to make this point about “all men” being at fault, the film necessarily can’t allow the Grenoble detectives to finally nab a single killer.

But of course, Clara’s curious attraction to bad boys and her generally impulsive nature was at the very least a significant factor in her fate. She was obviously flirting with this kind of snorting louche male for a deep-seated reason of some kind. Clara could have theoretically been a cautious or even withdrawn type, barely experienced in sex and sensuality and perhaps even prudish, and she still might have been torched by a sicko. But you’re not going to tell me that “playing with bad boys” wasn’t central factor.

Sensible women choose their lovers sensibly, and Clara didn’t roll that way. If you don’t use common sense in your romantic life, sooner or later the bad stuff will rub off.

So where did the bad-boy fetish come from? In The Limey (’99) we understood why Terrence Stamp’s daughter Jenny was attracted to dangerous men, but Clara’s dad (Matthieu Rozé) is a moderate mousey type and her mom (Charline Paul) is a diligent homemaker. So how and why did she develop the appetite?

The screenwriters (Moll and Gilles Marchand) don’t even toy with this emotional dynamic as they don’t subscribe to a belief that Clara might have flown too close to the flame. They seemingly believe that Clara was 100% innocent of any dangerous behavior by way of skunky boyfriends. I think that’s a dishonest attitude, and so I didn’t finally buy what the film was saying.

I saw the film with mostly older singles and straight couples, but there were at least two female pairs who were kind of sniffling and crushed at the end — the same emotional vibe I felt among women after a Toronto screening of Boys Don’t Cry.